Coronavirus: South Korea’s aggressive testing gives clues to true fatality rate

- With 140,000 people tested, the country’s mortality rate is just over 0.6 per cent compared to the 3.4 per cent global average reported by the WHO

- Various factors can influence this percentage, but scientists agree that all things being equal, it is more accurate when more people are tested

Within a month of confirming its first case of Covid-19 on January 20, South Korea had tested nearly 8,000 people suspected of infection with the new coronavirus that causes the disease. A little over a week later, that number had soared to 82,000 as health officials mobilised to carry out as many 10,000 tests each day.

Neighbouring Japan, on the other hand, tested only a fraction of that number, with fewer than 2,000 people checked on any given day since the beginning of its outbreak in late January. So far, more than 6,000 cases have been confirmed in South Korea and over 1,000 in Japan, if you include the Diamond Princess cruise ship that was quarantined in the Port of Yokohoma.

In the United States, where the number of confirmed cases has surpassed 100, health authorities had as recently as this week tested fewer than 500 people in total, hindered by legal and technical barriers to mass screening.

Which is where South Korea’s massive testing effort can come in, providing a valuable reference point for public health experts around the world who are starved of hard data – offering potentially the most comprehensive picture yet of the threat posed by Covid-19 to the general public.

And while experts caution that it is still too early to draw firm conclusions, the picture emerging in South Korea – which has the most confirmed cases outside China but with a more transparent political environment – suggests the virus could be less lethal than patchier data emerging from elsewhere.

“If we can test more people – whether they have no symptoms, mild or severe disease – the results, including the case fatality rate, are more accurate and representative when the whole disease spectrum is taken into consideration,” said David Hui Shu-cheong, an expert in respiratory medicine at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “Most countries just focus on testing the hospitalised patients who obviously have more severe disease, and [thus] the fatality rate is high.”

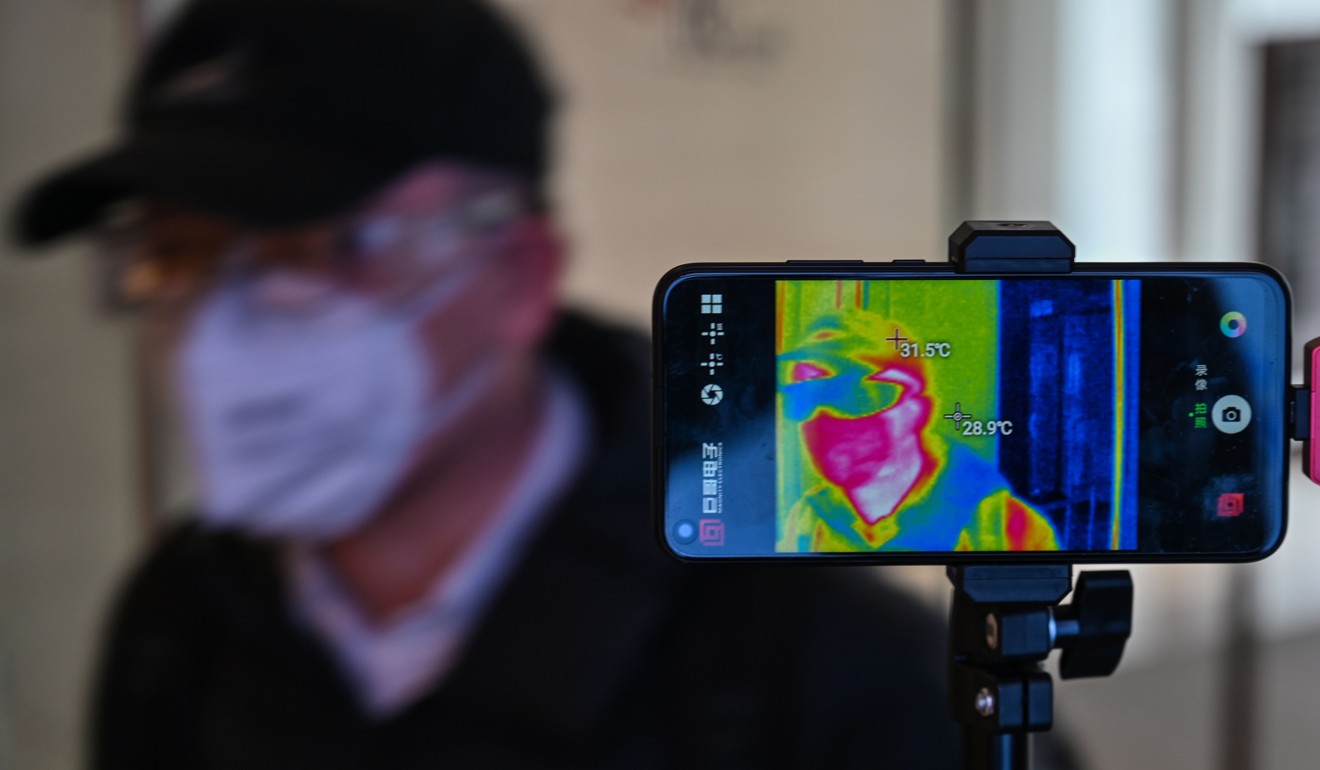

South Korea, which introduced a system to grant the rapid approval of testing kits for viruses after 2015’s outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome in the country that killed 38 people, has won international plaudits for the scale and speed of its screening regime, which includes drive-through stations that can test members of the public in minutes. This week, President Moon Jae-in went so far as to declare “war” on the virus and as of Thursday, health authorities had tested more than 140,000 people.

One question puzzling disease experts has been Covid-19’s mortality rate, which has seemingly ranged from 2-3 per cent in China up to 10 per cent in Iran, based on official numbers – though given the opaque nature of both countries’ political systems, these figures have been dogged by doubts, with some scientists suggesting that the illness caused by the new coronavirus is actually less deadly than Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome.

World Health Organisation Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus on Tuesday said the global mortality rate from Covid-19 recorded so far was about 3.4 per cent, higher than previous estimates - though this figure was accompanied by caveats that the rate could be lower when more was known about the disease.

Yet in South Korea, where the country’s Centres for Disease Control and Prevention on Thursday reported 6,088 cases and 40 deaths, the mortality rate appears to be hovering around 0.65 per cent.

While this is still several times more lethal than seasonal influenza, which kills about 0.1 per cent of the people it infects – 30,000-40,000 people in the US alone each year – South Korea’s rate is far lower than that seen elsewhere.

Although various factors can affect mortality rates, including the quality of a country’s health care system and the amount of public and medical knowledge about what to do in an outbreak, the number of people being tested is one of the most influential. All other things being equal, the more people tested, the more accurate the mortality rate will be.

William Schaffner, a professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, said South Korea had emerged as a “wonderful laboratory” for studying the virus.

“During the course of subsequent investigations, as we start testing more broadly, we discover, almost always, that there is a broader spectrum of illness,” he said.

“The more you test the more you are likely to complete the picture of the entire pyramid, and so the more you test, it becomes [self-evident] that the perceived fatality rate will diminish.”

The argument that South Korea’s lower death rate may be more representative of the risk posed by the virus has been bolstered by some of the data out of China, where more than 80,000 cases have been reported.

In a study released last month, the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention said the mortality rate among people whose symptoms started between January 1 and January 10 was 15.6 per cent, compared to just 0.8 per cent among those who showed symptoms between February 1 and February 11 – a possible indication that increased screening as awareness of the virus grew had detected more mild cases of infection. Chinese authorities have reported testing some 320,000 people in Guangdong province, but the total number of people tested across the country remains unclear.

Jeremy Rossman, an honorary senior lecturer in virology at the University of Kent in the UK, said he believed the true fatality rate was significantly lower than observed in China and especially the city of Wuhan – the epicentre of the outbreak – where about 4 per cent of patients are reported to have died.

“It is hard to know exactly which factors are at play in which country,” Rossman said, adding there may have been significant under-reporting of cases in Wuhan. “Regardless, I do think it’s likely that the fatality rate is closer to 0.5 per cent, which is indeed very good news.”

Schaffner, too, said he found a fatality rate of around 0.5 per cent broadly credible.

“It would be a cause for optimism and would stand in contrast with the way the coronavirus has been presented, particularly by television announcers, who almost invariably precede the word ‘coronavirus’ with the word ‘deadly,’” he said.

“Having a much lower fatality rate would put the lie to that, and although it would be indeed higher than influenza, it would be down in the seasonal influenza range and very different than Sars and Mers, the other coronaviruses that we know about that have jumped species.”

Others struck a more cautious note, pointing out the fatality rate in South Korea could rise as newly diagnosed patients begin suffering the worst effects of the virus in the days and weeks ahead.

“Given that cases typically die 1-3 weeks after onset, the case-fatality rate can artificially be reduced with an initial wave of newly diagnosed, new onset cases,” said Michael T. Osterholm, director of the Centre for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota. “Only after three weeks to a month can you calculate a reliable case-fatality rate for that group with onset the month before. So I think the case-fatality rate will go up, not down in Korea in the 30 to 60 days ahead.”

There is little disagreement, however, that countries such as the US, which bungled the production of its first diagnostic test kit and initially limited testing to travellers, should be learning from South Korea’s broad-based screening. Amid mounting criticism, the administration of President Donald Trump announced on Tuesday that the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention would lift all restrictions on testing, paving the way for mass screening by state, local and private laboratories.

“I’ve been yelling and screaming, as have many other people, about the need for testing capacity,” said Marc Lipsitch, a professor of epidemiology at Harvard University’s Harvard T.H Chan School of Public Health.

“The only way to know the severity spectrum is to test large numbers of people, and especially in outbreaks, it’s actually a really good setting to do it.”