02:02

Coronavirus: Singapore Jewel Changi Airport provides ‘glamping’ to satisfy travel cravings

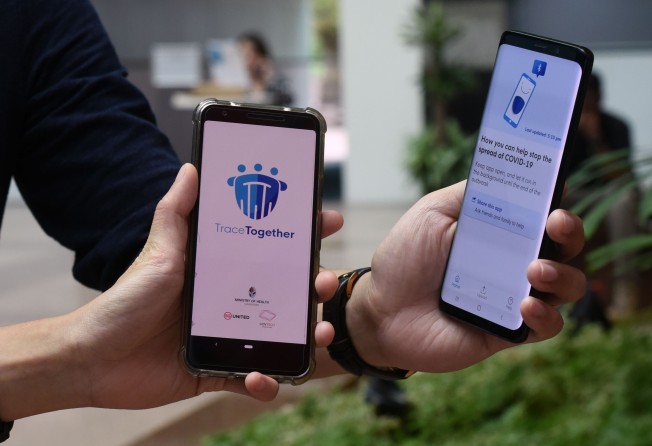

Singapore this week announced that the country might have the “world’s most successful” digital contact-tracing programme for the coronavirus, with 70 per cent of its population now on board. But three months after the TraceTogether app’s March launch, take-up rates were less than stellar, with many citing privacy concerns. So what changed?

Analysts say the 5.7 million who have now signed up to the app were prompted by the government’s strong messaging. In October, it made clear that while it was not compulsory for residents to download the app to their mobile phones or carry with them a government-issued token, they could be denied entry to places including restaurants and shopping malls starting at the end of December if they did not have either.

When announcing the programme’s uptake rate on Wednesday, Foreign Affairs Minister Vivian Balakrishnan, who heads the country’s smart nation initiatives, took to social media to thank Singaporeans for their trust and confidence in the government.

Indeed, analysts said Singapore’s numbers were unusually successful compared with other countries around the region that have rolled out similar programmes in recent months only to be met with lukewarm responses. They pointed out that there were several factors that could have stood in the way of citizens opting in to such programmes, including data privacy concerns and a lack of trust.

In May, three months after Singapore had launched its app, only 1.4 million people had downloaded it. At the time, authorities stressed that at least three-quarters of the population had to be using the app – which leverages short-distance Bluetooth signals between mobile phones to detect other participating users – for it to be effective.

Hsu Li Yang, an associate professor at the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health at National University of Singapore (NUS), said many Singaporeans did not understand or trust the authorities’ explanation that data was stored locally on the user’s phone – including location data – and only accessed if the user tested positive for Covid-19.

This was in line with an earlier survey by Singapore-based independent pollster Blackbox Research, which found that 45 per cent of respondents had not downloaded TraceTogether even though they had heard of it, with their main concern that they “did not want the government tracing their movements”.

02:02

Coronavirus: Singapore Jewel Changi Airport provides ‘glamping’ to satisfy travel cravings

PRIVACY CONCERNS

Teo Yi-Ling, a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies’ Centre of Excellence for National Security, suggested that trust was at the heart of the issue, adding that she felt there was significant concern among the population about privacy, mostly stemming from past data breaches of government databases. In June 2018, for example, hackers copied the hospital records of more than 1.5 million patients, of which 160,000 had information about their medications, in an incident described by authorities as the “most serious breach of personal data” in Singapore.

“The regular Singaporean may trust the government in other aspects of running the country, but because of these breaches, the jury may be out as regards trust in the government’s ability to secure data,” she said.

Privacy concerns aside, Lawrence Loh, an associate professor at the NUS Business School who also heads the Centre for Governance, suggested that the initial adoption rate was low because of Singaporeans’ hesitancy towards accepting new initiatives. “People naturally have inertia in the adoption of new technologies, and some may even be scared of trying unfamiliar things,” he said.

There were also concerns that Singapore’s senior citizens, many of whom do not own smartphones, would be left out of the contact-tracing programme. This led to the launch in June of TraceTogether tokens – small, dongle-like devices that work much the same way as the phone app, exchanging Bluetooth signals with other nearby tokens or phones running the app.

It was first distributed to the vulnerable elderly, but was later expanded to the general population. Just this past week, authorities said the country’s hundreds of thousands of students would be receiving the tokens, while expecting 5 million tokens to be given out by the end of February – meaning close to 90 per cent of Singapore’s population would be on the contact-tracing programme by then.

Teo noted that there was an initial rush among citizens to collect the token, with local media reporting long queues at collection stations. She said this largely reflected public acceptance of the token – not only did it solve the problem of battery drainage that the mobile-phone app causes, it also addressed concerns that the app might access private data.

“You could say that doing this is akin to keeping your house keys separate from office keys, so there is not a single point of vulnerability or failure leading to severe compromise,” she said.

Loh said the government’s greater outreach and improved awareness in implementing the programme had also helped assuage Singaporeans’ privacy concerns. Notably, he said that adopters were preparing for the time when using the TraceTogether app or token would be needed to access public places, such as restaurants and shopping malls.

“The consideration by the ordinary Singaporean is a more pragmatic one – if the app or token is required to get into locations like malls or restaurants, then by all means, they jolly well get it and use it,” he said.

Hsu, the associate professor at Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, said Singapore’s achievement of a 70 per cent uptake rate would help shorten the time taken to test and quarantine suspected cases, and would potentially reduce the size of Covid-19 clusters.

Teo Yik Ying, the dean of the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, added that while such a system would not completely replace manual contact tracing, it would significantly reduce the complexity of the contact-tracing investigation process.

“The benefits are clearly the gain in speed and comprehensiveness in the tracing, since identifying exposed contacts will not need to rely on an individual’s recollection,” Teo said. These gains, he added, could be significant if a country was facing a large-scale outbreak, and where contact-tracing capacity might be limited.

REGIONAL STRUGGLES

While Singapore has been able to nudge its population to join its contact-tracing programme, other countries and regions have struggled to do the same. Japan, for example, launched its contact-tracing app in June, with 4.4 million downloads the first week. But receptiveness then slowed dramatically, and there were only 7.69 million users as of July – the last reported figures – out of an adult population of about 105 million. Meanwhile, Hong Kong rolled out its “Leave Home Safe” mobile app last month, but it was met with a mixed response, with usage difficulties and privacy fears cited among the top concerns.

Loh, the NUS Business School professor, said adoption rates in different countries and regions depended on unique contexts and cultural settings. For Hong Kong, he said there was a seeming reluctance by the populace to use technology, which could be solved by adopting a carrot-and-stick approach – incentivising adoption through discounts for services or mandating adoption by refusing entry to public places.

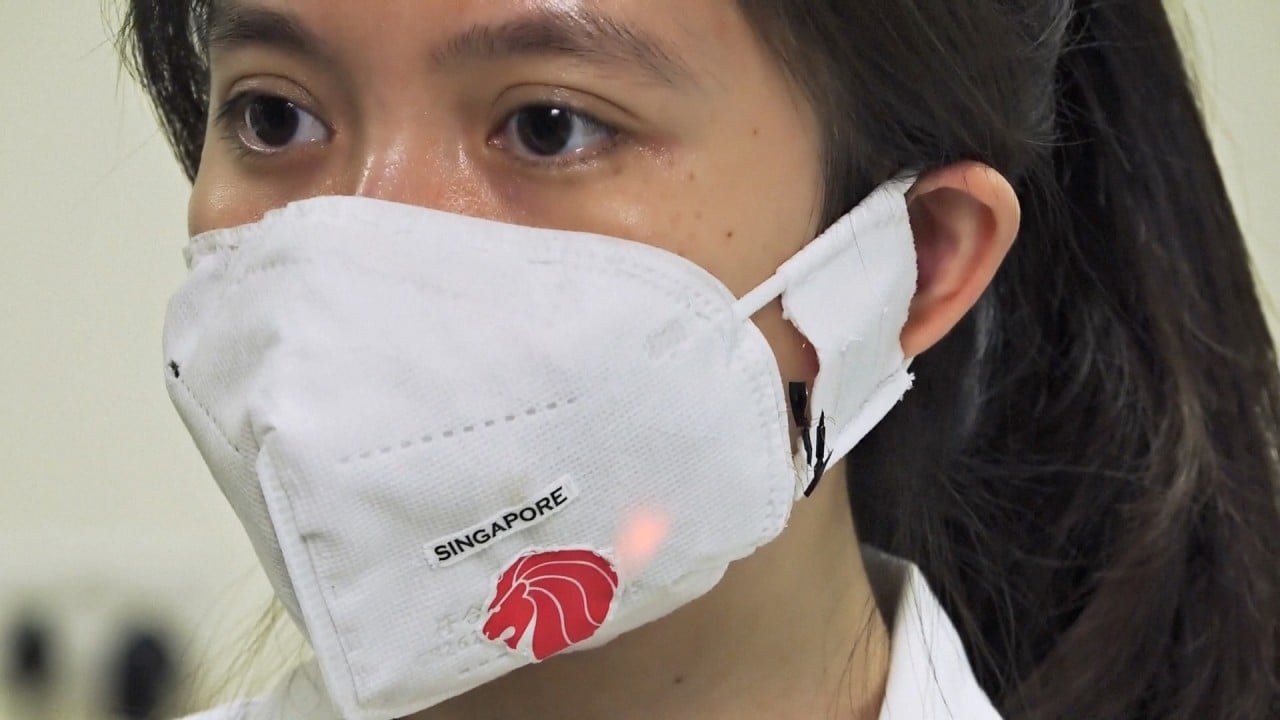

01:27

Smart masks from Singapore can help monitor patients for signs of illness including Covid-19

Public trust in the government was also part of the equation, Hsu suggested, saying that even in a place like Singapore, where trust in authorities is high, the city state took several months to rally a significant portion of the population to download the app. In the case of Hong Kong, Teo Yi-Ling of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies said public trust in the authorities and institutions had taken a “massive battering” in recent months, and that this tepid response may be a reflection of public sentiment.

Teo said governments needed to continually build and maintain trust, be transparent in their undertakings, and communicate messages sincerely, clearly and appropriately. They should also include citizenry in their decision-making processes, she added.

Teo Yik Ying, the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health dean, said if governments wanted to rely on the people to install and use a contact-tracing app on a voluntary basis, the uptake would likely be poor. There would also be gaps in the coverage as young children and the elderly are less likely to have mobile phones, he said.

“If the governments do intend to rely on digital contact tracing to augment the manual contact tracing efforts, it will be important to go beyond just the app and also consider how to allow the whole population to possess the technology,” he added.