Indonesia’s clean energy dream: a victim of coronavirus, or politics?

- Although blessed with abundant sources of clean energy, Indonesia’s potential remains untapped as it focuses its resources on defeating Covid-19

- Analysts say the sector is being held back by the political elite, who ‘don’t want to lose the opportunities of securing profits’ from coal, oil and gas

Denia Isetianti has long suffered from climate anxiety – the mix of depression and affliction arising from confronting the facts that the globe is heading towards a climate catastrophe. The feelings grew stronger after she became a parent.

“What’s going to happen to my kids?”, the 34-year-old mother of two asked.

She and her family live in the Indonesian capital of Jakarta, one of the most polluted cities in the world. Parts of the city are expected to be submerged by 2050 as a result of rising sea levels and excessive extraction of groundwater.

Denia, a corporate lawyer, believes that living a more environmentally friendly lifestyle is the only way to ease her fears of impending doom. In 2019, she took a huge step toward fulfilling that goal by building an eco-friendly house with solar panels on the roof even though the modules did not come cheap.

But in the world’s fourth most populous country, Denia is one of just 2,346 electricity customers who had voluntarily installed rooftop solar panels on their houses by June 2020.

Situated in the Equatorial Pacific Ocean, where solar, water and geothermal resources are abundant, Indonesia has plenty of renewable energy options, yet the potential for using them remains untapped.

David Firnando Silalahi, a PhD candidate who researches solar energy at Australian National University, said the archipelagic nation could generate 640,000 Terawatt-hours (TWh) annually from solar energy alone – equivalent to 2,300 times’ Indonesia’s entire power production in 2018.

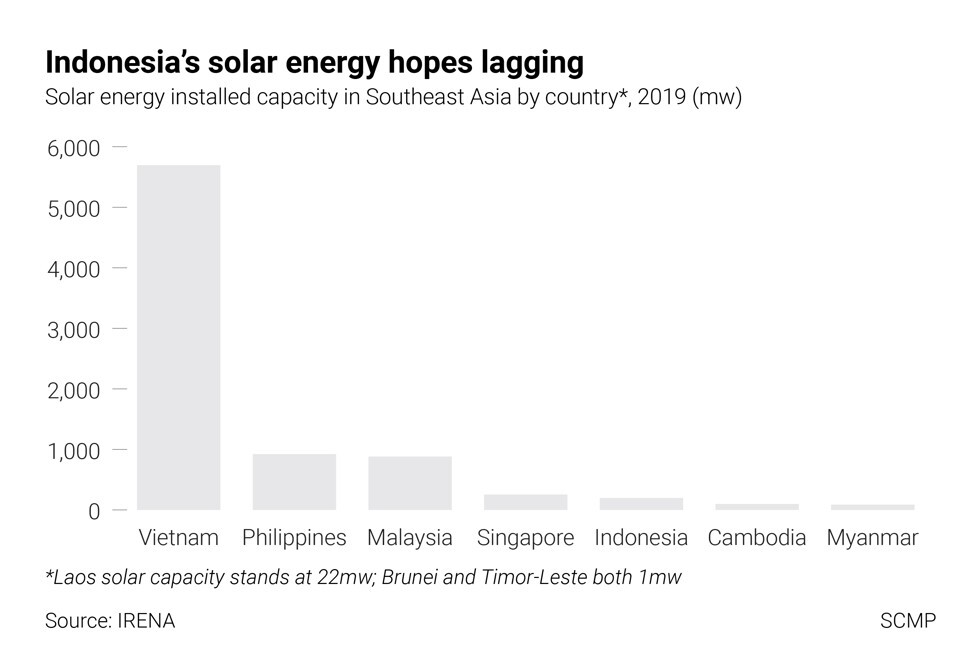

Yet solar energy contributed only 0.04 per cent to the country’s power production in 2019, and Indonesia’s installed solar capacity as of the end of 2019 was even smaller than that of Singapore, the tiniest state in Southeast Asia, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency.

London-based information provider IHS Markit predicted that the share of non-carbon energy in global demand would boom in 2020 as a result of the combination of the coronavirus pandemic’s impact on fossil fuel demands, increased investment in renewables and growing concern over climate change.

In Indonesia, though, clean energy development is entangled in the coal-financed political regime and now by the coronavirus pandemic. Indonesia is still struggling to contain the spread of Covid-19, and it has a mortality rate higher than any other country in Southeast Asia and South Asia except India. Its attempts to at least contain the spread of the disease have pushed all of its other stated priorities – including increasing its use of clean energy – to the side.

The task becomes even more difficult considering Indonesia’s energy use heavily relies on fossil fuels. Coal is the dominant source of energy in the power sector, accounting for nearly 60 per cent of electricity generation in 2019.

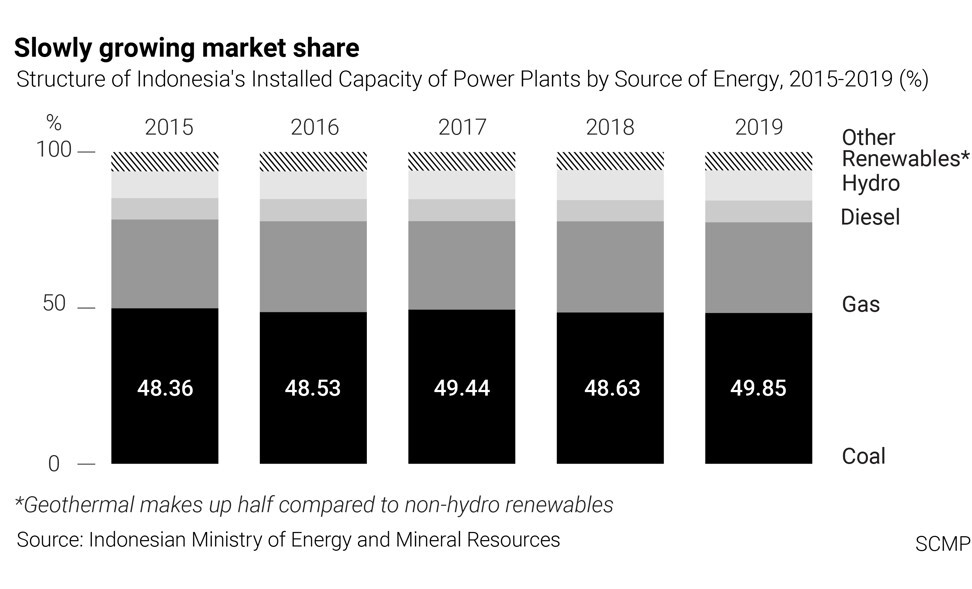

The share of coal in Indonesia’s installed power generation capacity increased from 38.2 per cent to nearly 50 per cent from 2010 to 2019, while the shares of solar and wind energy remained marginal, amounting to just 0.21 per cent and 0.22 per cent in 2019.

“There is a strong political power which does not like the development of renewable energy in Indonesia,” said Agus Sari, an environmental expert and a lecturer at the Bandung Institute of Technology in West Java. “They don’t want to lose the opportunities of securing profits from running the non-renewables.”

In Indonesia, coal is not only a heavily traded commodity, but the industry is an integral source of political financing, with presidential candidates, various ministerial officials, parliament members and local elites fuelled by the money that flows from coal mining and power firms.

In the 2019 presidential election, Joko Widodo declared that almost 90 per cent of his campaign financing was linked to mining businesses, according to Indonesian NGO The Mining Advocacy Network. His rivals in that election, Prabowo Subianto and Sandiaga Uno, were long-time moguls in the fossil fuel and mining sectors, it said.

The country is far from reaching its target of boosting new and renewable energy to a 23 per cent share of the national energy portfolio by 2025 and 31 per cent by 2050. However, the political elites’ interest in keeping the coal sector moving ever forward has hindered the development of the clean energy sector.

The government took at least six years to finally submit a Renewable Energy Bill in January 2020 for the national parliament to review, and it was considered a priority measure before the coronavirus pandemic hit in March 2020, suspending consideration of the bill until September. The bill is expected to help accelerate renewable energy development in Indonesia.

Renewable energy power producers in the country also lack regulatory clarity and incentives to implement projects.

The government’s 2017 renewable energy tariff scheme is often cited as the top roadblock for renewable energy projects. It caps the purchase price of solar and wind power at 85 per cent of the average cost of electricity generation for the local region, making it difficult for projects to achieve economic viability, said Joo Yeow Lee, associate director of gas, power and energy futures for IHS Markit.

In February 2020, the government rolled out a new regulation to bring minor changes to the 2017 regulation, liberalising some of the procurement requirements and stipulating that state power producer PLN must prioritise energy procurement from renewable power plants, but the move failed to bring about a long-awaited regulatory overhaul because the notorious pricing system remained intact.

01:46

Indonesia ends search operation for victims of Sriwijaya Air plane crash

PANDEMIC EFFECT

The development of the renewable energy sector has largely become a casualty of the government’s all-out attention to containing the coronavirus, and is no longer considered a policy priority, according to Fabby Tumiwa, the executive director of the Institute for Essential Services Reform.

In addition to the suspended parliamentary discussion on the Renewable Energy Bill, a much anticipated presidential regulation to set a new feed-in tariff scheme (to replace the one from 2017) and a procurement mechanism for renewable energy has been delayed. The government had started to draft the regulation before the pandemic and aimed to release it in March or April 2020.

In December, Indonesia was ranked at the lower end of the Greenness Stimulus Index, as measured by the international economics consultancy Vivid Economics – indicating that the economic stimulus package the government passed to cushion the blows of the pandemic were expected to have a damaging effect on the environment.

And even amid the pandemic, the government managed to approve the building of several large coal-fired power plants, said Yuyun Indradi, the executive director of Indonesian environmental organisation Trend Asia.

Yuyun noted that in 2020 at least three new coal power plants – Java 9 and 10, Tanjung Jati A and Indramayu – were added to the pipeline, and the existing Tanjung Jati B and Jawa 7 plants had their capacities expanded.

David, the solar energy researcher at Australian National University, who has worked for Indonesia’s Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry since 2009, said he hoped the pandemic would prompt the government to rethink its renewable energy plans, as in the long run “maintaining coal power plants will be more costly than renewable power plants”.

Elrika Hamdi, an energy finance analyst at the US-based Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, said that for an archipelagic country that cannot easily trade electricity with neighbouring countries, using a distributed power generation system, where electrical generation occurs through a wide variety of small grid-connected devices, would be better than building huge fossil fuel-fired plants.

A GREENER FUTURE?

Agitating for renewable energy and against the continued and extensive use of coal in the country – and the coal-financed politics that come with it – is not an easy task, especially amid the pandemic, but for environmentalists like Denia, such actions are necessary for the health of Indonesia and her family.

“We need to make changes to save the environment, and everything starts from home,” she said.

Fabby of IESR has launched the One Million Rooftop Solar PV Initiative, which is aimed at increasing Indonesia’s rooftop solar photovoltaic installed capacity to one gigawatt – enough to power 890,637 Indonesian households. As of June 2020, installed capacity was only enough to power 10,242 households.

Meanwhile, the motivation for some to switch to clean energy is due to more than just public policy or economic considerations.

Denia and her family had to cancel their holiday in 2020 because the installation of the rooftop solar panels cost them around US$5,300. But she believes the cost was worth it because the solar panels should shave 40 per cent off her electricity bill every month.

More important to her, though, is that her children can plan for a future where they need not fear breathing polluted air.

“I want to contribute something to the environment and provide a better future for my kids,” she said.