Food fight, lah: who will eat their words in Singapore-Malaysia hawker battle?

In Malaysian food courts, there’s something on everybody’s lips – a lingering question about whether, when it comes to comparing cuisines, Singaporeans are just being ‘kiasu’

It is past 6pm in a suburb just outside Kuala Lumpur and an outdoor night hawker market – that staple of Malaysian daily life – is slowly coming to life.

Plastic stools and foldable tables are dragged into place, and the smell of char kway teow, curry mee, and satay wafts through the air as hawkers prepare piping hot meals for a clientele that runs the gamut from the after-work crowd to nattering retirees.

There are no Michelin or Bib Gourmand guides luring customers to this spot – only word of mouth.

“Can finish by 10pm,” curry mee hawker Lee tells This Week in Asia of his usual working hours as another customer orders a bowl of his speciality noodles drenched in spicy, coconut-laced gravy.

Some 350km south of Petaling Jaya, in the Amoy Street Food Centre within Singapore’s central business district, Gwern Khoo and Ben Tham keep an equally gruelling schedule at A Noodle Story, their Bib Gourmand-featured stall that serves a hybrid, wanton noodle-Japanese ramen dish they call “Singaporean ramen”. Theirs is by far the most popular stall in the food centre – helped on by scores of curious tourists ticking off their list of must-have Singaporean hawker fare.

The three hawkers refuse to be drawn into the debate raging on both sides of the Singapore-Malaysia Causeway: who has the better hawker fare?

That question touches a raw nerve like nothing else in the two food-crazed neighbours – where eating and criticising the other side’s cuisine are national pastimes.

Home to mouth-watering cuisine as diverse as the two countries’ mostly migrant populations, Singapore and Malaysia have for the decades since their acrimonious split in 1965 vied for the title of being Southeast Asia’s undisputed makan [food] heaven.

And it’s a food fight that politicians have proved willing to get involved in on more than one occasion. In 2009, then Malaysian tourism minister Ng Yen Yen prompted weeks of banter with her suggestion that traditionally Singaporean dishes like Hainanese chicken rice and chilli crab were in fact Malaysian fare “hijacked” by the island state.

In August, Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong upped the ante, announcing in a policy speech that the city state would soon apply to have its “hawker culture” listed on Unesco’s intangible heritage list.

Singapore will submit its nomination to Unesco in March, with a decision to be announced in 2020.

In Malaysia, foodies say while they can endure the constant banter about makan from their southern neighbour, the bid for UN recognition just reinforces stereotypes that Singaporeans are kiasu (a colloquial term for “afraid of losing”).

“If Singaporeans suddenly claim their food is the best, good for them, enjoy – doesn’t mean I am going to go there, because I am happy with my own here,” said Malaysian celebrity chef Redzuawan Ismail, an Anthony Bourdain-type figure commonly known as “Chef Wan”.

Said Chef Wan: “The government of Singapore should be more sensitive about other people’s feelings in the region. Respect works both ways. Don’t be so kiasu. There is nothing wrong with being humble.”

And Wazir Jahan Karim, a Malaysian cultural conservationist, said Singapore should be more specific if it wanted to claim all or part of regional hawker culture as its own. “Singapore can stake a claim, but the culinary history of Malaysia is so much richer and more authentic,” she said.

Similar barbs have been traded online since Lee’s speech on August 19.

Some Malaysian food industry figures are less biting than Chef Wan and Wazir, warning that protesting too loudly gives the impression the Malaysian hawker community is insecure when it has no need to be.

“Singapore copies us a lot. But we don’t need to follow them,” said Yow Bow Choon, president of the Federation of Hawkers and Petty Traders Association Malaysia. Yow said he was counting on Malaysia’s new-age “hawkerpreneurs” who are reinventing their craft through new technology and experimentation to maintain “superiority” over Singaporean food.

Said Yow: “In other countries young people don’t want to be hawkers, but in Malaysia nowadays young people are banyak berani [Malay term for ‘very brave’] and bring in cuisines from Japan, Korea, other countries.”

Khoo from A Noodle Story said he was amused by the war of words between the hawker communities.

He said Singapore’s hawkers were not as worked up as their Malaysian counterparts.

“I guess between neighbours and friends this type of thing is normal, lah,” Gwern said. “We like to always compare, see who is better. But don’t forget the people are almost the same. We were part of Malaysia once upon a time, we are immigrant societies.

“Our food is a mix of Indian, Malay, Chinese. It is not just about ‘this is Singapore food’ or ‘this is Malaysia food’. Both countries are melting pots and that’s what makes the food special.”

For Malaysian cultural activist and author Lee Su Kim, that commonality is why it makes little sense for either side to claim the title of makan heaven.

Such claims ignore “that unique shared culinary heritage that the peoples of Southeast Asia have created, enjoyed, celebrated through the centuries and shared regardless of national boundaries”, said Lee.

Others say the sooner everyone turns their attention to more pressing issues – perennial labour shortages, rising costs and a changing market dominated by food delivery apps – the better.

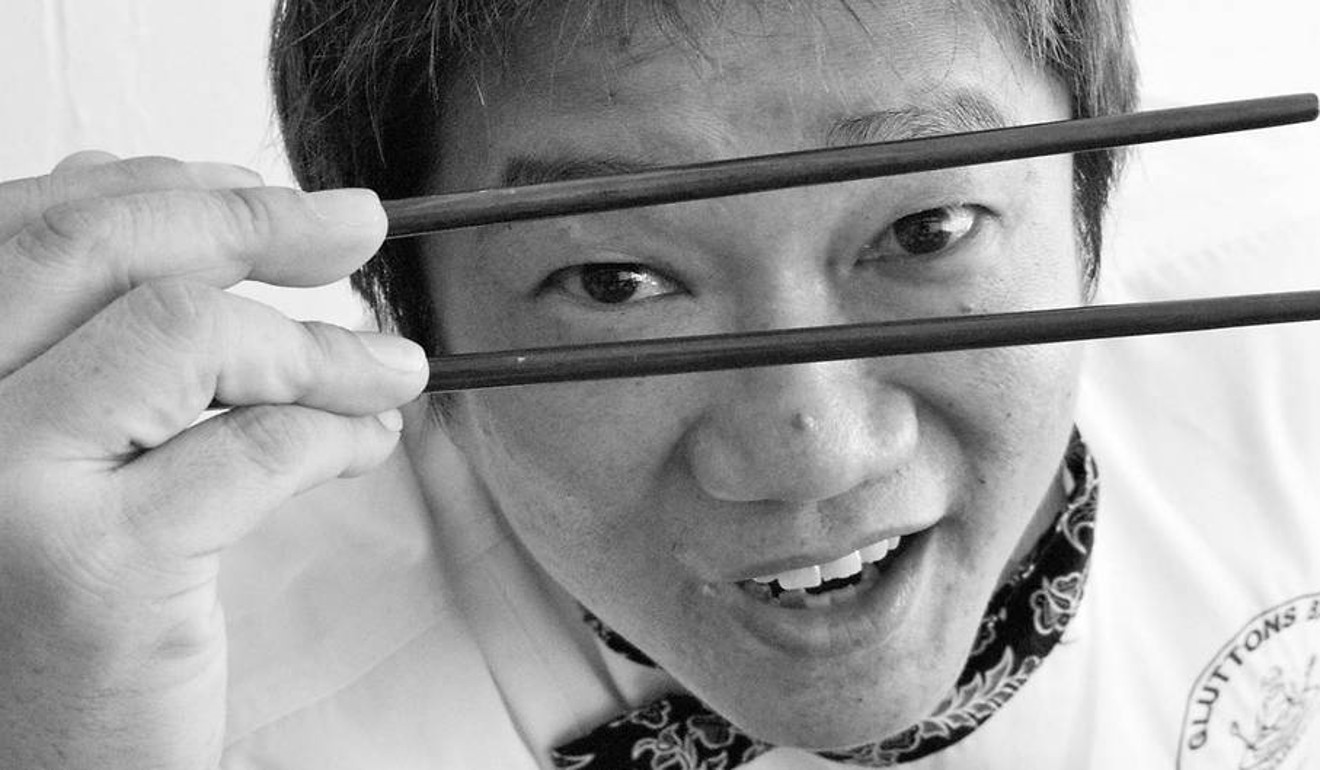

The Singaporean street food guru KF Seetoh, the city state’s answer to Bourdain and Chef Wan, said on Facebook he was refusing to field questions on “this Unesco food culture thingie”.

“Waste my time. Throw a month-old infant into that shallow pool of thinking [and it] won’t drown.” ■