What it’s really like to live in South Korea’s Parasite-style semi-basement homes

- Semi-basement apartments, known as ‘banjiha’in Korean, have been thrust into the spotlight this year by the Oscars success of Bong Joon-ho’s film

- Cramped and dingy, they are nonetheless relatively cheap – but falling demand means they could also soon become a thing of the past

Twice in his life has 26-year-old Lee Hyeon-woo considered himself really lucky.

The first time was when he was accepted into one of South Korea’s most prestigious art universities, and the second was when he found an apartment in Seoul – even though it was mostly underground.

Semi-basement apartments, known as banjiha in Korean, have been thrust into the spotlight by the success of Bong Joon-ho’s Oscar-winning Parasite , which made history this year as the first foreign-language film to scoop the best picture award.

The fictional portrayal of a poor family struggling and scheming to escape their dingy, squalid banjiha is used to darkly comic effect in the movie, but it is also an everyday reality for thousands of ordinary Koreans.

Lee has lived in his 260 sq ft banjiha, five steps below street level, for four years now. Though he has a large window in his room, its only view is of a towering stone wall at the end of an alleyway.

“I could sleep until 3pm because I don’t get woken up by sunlight,” Lee said. “But I still consider myself lucky because there’s no mould, no bugs and no smell like other places … and it’s dirt cheap.”

Hidden away among the bright lights of a city better known for the glamour and success of its K-pop idols and family-owned conglomerates like Samsung, banjiha go largely unnoticed except for the tops of their barred windows peeking above ground.

In Haebangchon – a former shantytown whose name translates as “liberty village” and which housed defectors from the North immediately after the end of the Korean war in 1953 – lives poet and writer Lee Seung-cheol, who has been in his two-room banjiha for the past 15 years. “No one lives in a banjiha because they want to, it’s because they don’t have enough money,” he said.

The 63-year-old has learned to live with changing the flat’s wallpaper every two years because of the constant humidity, as well as a lingering, musty smell from the mould that “always comes up in the summer”.

“The biggest inconvenience is the noise from upstairs. You can hear everything because you’re at the bottom,” he said.

Yet he shrugs off the shortcomings, stressing that banjiha are “perfectly fine to live in” as long as you take care of them properly.

Not everyone would agree. University student Baek Hyun-young stayed in a banjiha for a semester before moving into a rooftop flat and said it felt more like a box to sleep in than a home.

“My daily life felt intruded upon because I knew that anyone outside could watch me inside my room through the windows anytime,” the 23-year-old said.

About 366,000 of South Korea’s 20.5 million households were living in banjiha in 2018, according to the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport.

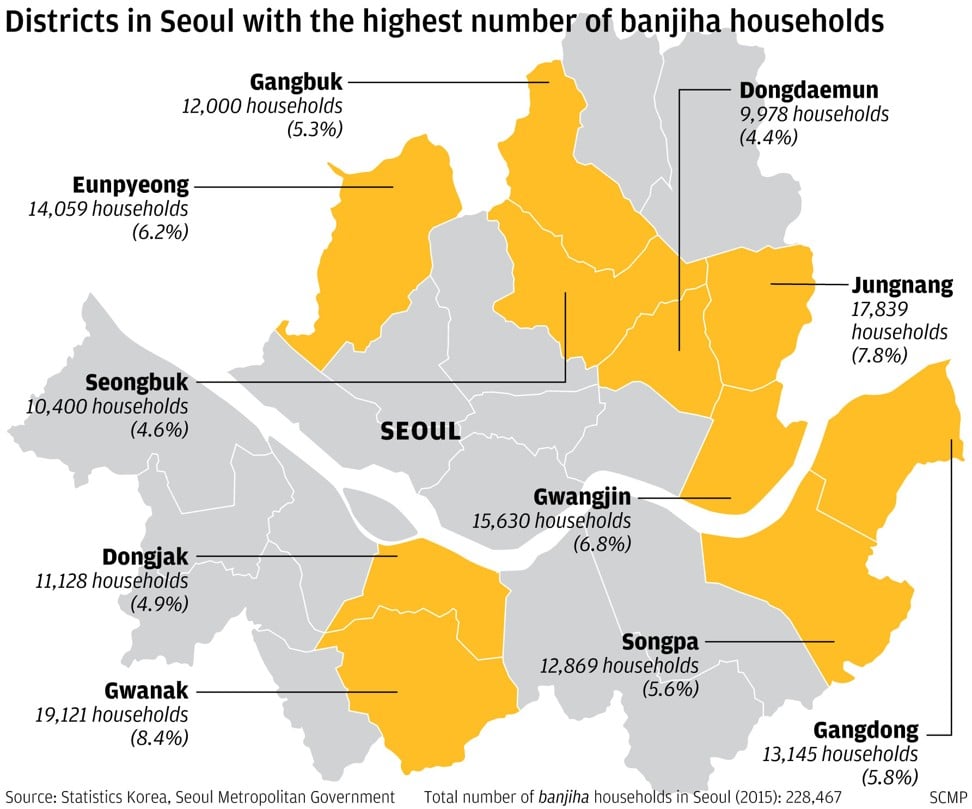

Most of these – 63 per cent – are in Seoul, according to the latest figures from state-run Statistics Korea, which found in 2015 that they accounted for 6 per cent of all of the capital’s households.

Banjiha can trace their roots back to the 1970s when the government mandated that basements be built to serve as bunkers in case of any North Korean attack, according to Park Mi-seon, a research fellow at the Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements think tank.

As no peace treaty between the two Koreas was ever signed, the two are still technically at war, though an uneasy truce has been in place since an armistice in 1953.

Because of this, it was illegal to live in banjiha at first, but rapid urbanisation and the influx of migrants from rural areas to seek jobs in Seoul prompted the government to relax these restrictions.

Changes to the building code in 1984 allowed the basements to be built half above street level, as opposed to at least two-thirds being below ground as before, so as to increase their liveability, said Park, whose research speciality is low-income housing.

Decades later, as South Korea’s economy took off and property prices surged, banjiha, along with goshiwon – tiny, windowless rooms in shared houses – and oktapbang – makeshift shacks on rooftops of low-rise buildings – have become the housing option of last resort for young people or those experiencing financial difficulties.

In Seoul, the average price of an apartment reached 899 million won (US$753,230) last month, after 10 straight months of rising property prices, according to KB Kookmin Bank.

That is more than 400 times the average monthly wage of the city’s banjiha residents, which was about 2.19 million won (US$1,820) in 2018, according to official data.

The typical monthly rent for banjiha, on the other hand, ranges from 200,000 to 500,000 won (US$170-420), with a security deposit of 3 million to 10 million won (US$2,500-8,400) that has to be paid up front.

Despite rising property prices putting a squeeze on less well-off tenants, fewer people are actually choosing to live in banjiha, with the number of households inhabiting these semi-basement apartments falling from 586,000 in 2005 to fewer than 400,000 today, according to official statistics.

A property agent who works in Seoul’s northeastern Jungnang, the district with the highest number of banjiha households, said up to 15 per cent of below-ground flats in the area were left empty at any given time.

“The demand for banjiha is decreasing more and more every day,” said the agent, who declined to be named,attributing the dwindling demand to young people who have no experience of living in banjiha being put off by the shabby living environment.

In the early 2000s he would rent out as many as 50 banjiha a year, but nowadays he rented out fewer than 20, he said,predicting that “ultimately, there won’t be any more banjiha” as ageing buildings are torn down and newer homes are more likely to have parking spaces than semi-basements, thanks to a 2003 change to the building code.

For those still occupying banjiha, the Seoul metropolitan government announced (a week after Parasite ’s Oscar win) that 1,500 households would receive financial help to upgrade heating systems, and install air conditioners, ventilation systems and windows.

The initiative, part of ongoing schemes to improve living conditions for old apartments, will cost the government and its partner, the Korea Energy Foundation, 1.1 billion won, with a cap of 3.2 million won in subsidies per household.

“It’s a good first step, but of course it’s not enough,” said Park from the human settlements think tank, who suggested that a comprehensive survey of the living conditions of banjiha residents needed to be done first.

Provision of public housing for rent – which accounts for only about 8 per cent of the country’s housing stock at present – also needed to be increased in the long term, with more providers, such as municipalities and civic organisations, introduced to limit reliance on the current sole provider, the state-owned Korea Land and Housing Corporation, Park said.

Lee Hyeon-woo, however, does not plan on waiting for the government to build more affordable housing. He is content to carry on living in the home that he has made his own, until he finds a job that will get him into a flat above ground with plenty of sunlight.

He has painted the walls sky blue – a colour he said was known to boost creativity – and his doors a bright pink. When he needs to concentrate, he switches on fairy lights and mood lights that transform his room into a vibrant, multicoloured space. And in one corner, he has set up a mini home gym he bought with a month’s salary from his previous part-time job so he can stay active, too.

“I want to show other people that banjiha can be cosy,” he said. “People might look down on us because we live at the very bottom, but I believe this place is like a shield, letting young people live here until they are able to make it. It’s a place that protects my dreams.” ■

Additional reporting by Lee Chae-wan