Bangkok’s Cham community strive to keep matriarchal heritage alive through silk weaving

- Passed on down the generations dating back to their time in Cambodia, the silk-weaving heritage of the Chams is a crucial link to their past

- One renowned silk brand in the Baan Krua community is still going strong today, decades after being a main supplier for Jim Thompson’s company

Traces of the matriarchal heritage of the Cham people can still be found in their much sought-after handicrafts, and are especially evident in their complex woven silk work – an art the Cham community in Bangkok is struggling to preserve as it comes under increasing pressure to assimilate into modern life.

The Cham, a Muslim group of ethnic Malays who once ruled the ancient Kingdom of Champa, in present-day southern Vietnam, were well-known for their matriarchal and Hindu-influenced society before Islam spread eastward into Southeast Asia and the Indochinese Peninsula.

The group was pushed out by the Vietnamese at the end of the 17th century before settling in Cambodia, where a series of wars as well as French colonisation drove them to Thailand. They now make Bangkok’s historic Baan Krua community their home and continue their centuries-old silk-weaving artistry.

Nipon Manuthas, 70, a Baan Krua resident, recalled how his mother built a thriving silk weaving business in Bangkok during King Rama VI’s reign in the 1910s and 1920s.

He said his family’s weaving techniques and skills were passed from generation to generation, but originated in present-day Cambodia.

A more recent wave of Cham people came to Thailand during the reign of King Rama V and settled in Baan Krua, on the Saen Saep Canal in the centre of Bangkok, which connects to the Chao Phraya River and outlying commercial districts.

“Our community began weaving when the Saen Saep Canal was dug [in 1837] because we could load the silk on boats to sell,” he said.

“When we moved from Cambodia we brought the looms here,” he said. “Most of the weavers were women. My mother weaved at home and in the palace, so it can be said that women were the breadwinners.”

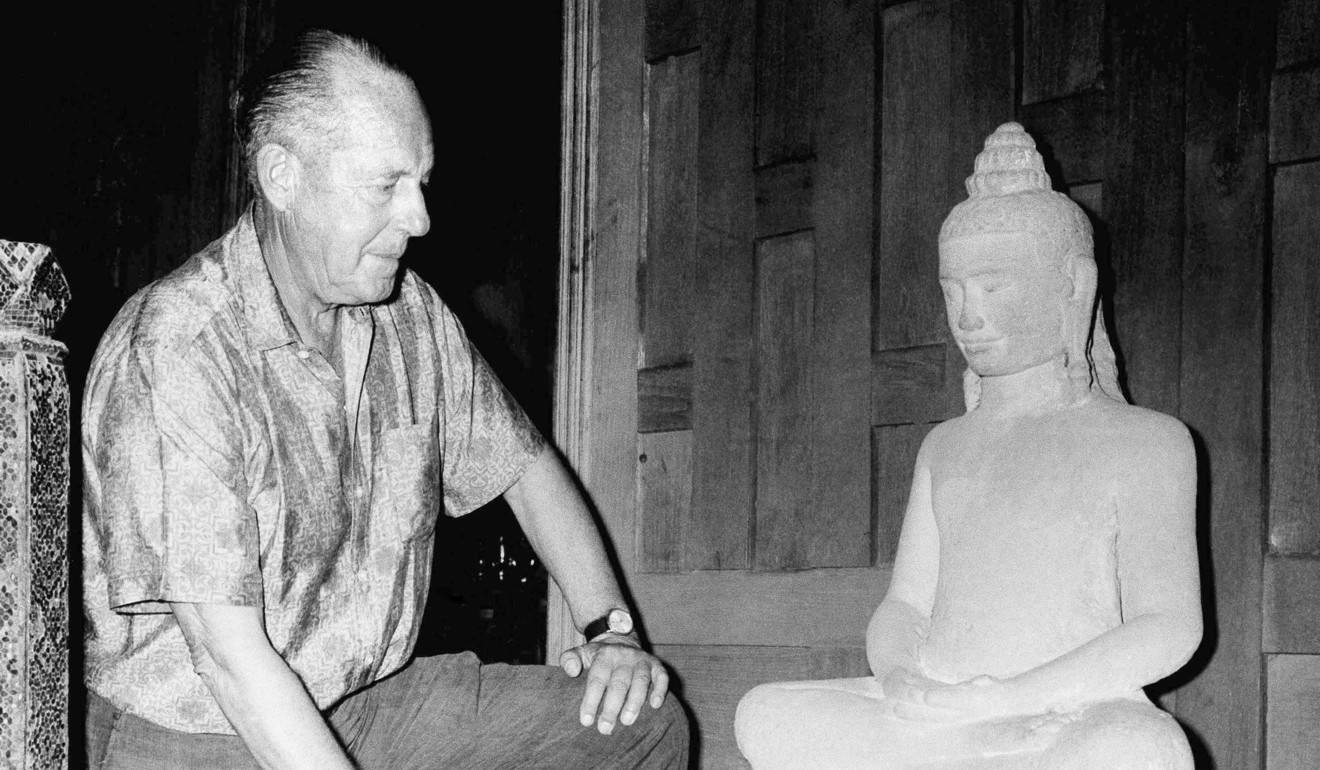

It was from those humble beginnings that Nipon built his own business on the back of Phamai Baan Krua, or “Baan Krua Silk”.

At the height of Phamai Baan Krua’s popularity after World War II, 300 looms run by a group of eight or nine families in the Baan Krua community worked round the clock to feed demand coming from one source: Jim Thompson, the American entrepreneur who helped revive Thailand’s silk industry in the 1950s and 60s through his Thai Silk Company, which was founded in 1951.

“After Jim disappeared in 1967, the orders just stopped, because we dealt with only him. He used to walk here from across the street and made the order,” Nipon said, referring to the still-unsolved disappearance of Thompson in Malaysia’s Cameron Highlands.

Nipon said that as the Thai Silk Company’s Jim Thompson brand grew, almost all of the Baan Krua looms – 297 out of 300 – and workers were moved to the brand’s factory outside Bangkok to cater to Thompson’s expanding business.

Today, though, Nipon still uses three of the original looms in his family-run workshop, which produces about 700 yards (640 metres) of silk a month. The silk is sold at some shopping malls in Bangkok at a cost of 500 to 1,200 Thai baht (US$15 to $28) per yard.

“I have a few employees who worked with and were taught by my mother,” Nipon said. “All of them are in their 50s or 60s now. I can’t find young people who want to learn the skills.”

Without this essential weaving knowledge being passed to the younger generation, traditional Cham identity faces an existential threat, said Sukre Sarem, an independent researcher on Muslims in Thailand.

Sukre said that in addition to gradually losing their weaving skills, their Khmer speaking skills are also at risk. “Some Cham people from Cambodia who are older than 80 years old in Thailand can still speak the Khmer language, but people younger than 50 mostly cannot.”

Sukre added that the Muslim identity and the statelessness of the Chams over time subsumed their ethnic identity. “Many of them are married to Muslims of other ethnicities and have assimilated themselves into other Muslim communities in Thailand,” he said.

Still, he added, the Cham’s division of labour between women and men – the men historically fished, while women processed the fish and controlled other means of production at home – persist even today, although Nipon said he had “no knowledge of how the Chams were ruled by women in the old days” before adding that “Muslims are one regardless of race or ethnicity”.

And at least one physical testament to the Cham people and their role in Thai history can still be found in the Baan Krua community today, in the Jami Ul Khoy Riyah Mosque, which was built in 1787 – five years after Bangkok was founded as the new capital. The land of Baan Krua was bestowed to the Chams by King Rama I who reigned from 1737 to 1809.

Regardless of the Cham’s past, though, Nipon is doing what he can to save the traditional art of silk weaving – and he’s adding a woman’s touch to the business. Although his daughter does not weave, he said he hopes her degree in graphic design can help with Phamai Baan Krua fabric design.

“I am still looking for apprentices,” he said, explaining that although men usually help dye the silk, “Women are better at weaving sophisticated fabric designs.”