In Okinawa, Ryukyu royalty descendant stands firm on independence from Japan

- Self-rule campaigner aims for prefecture’s freedom to choose its own security alliances and diplomatic ties

- An independent Ryukyu would create a ‘recreation centre’ that would welcome warships from every nearby nation, including North Korea

In 1470, King Sho En was on the throne of the recently united Ryukyu Kingdom, overseeing the prosperous and progressive years of the Second Sho Dynasty. Now, 550 years later, a direct descendant of the king has ambitions of similarly bringing together the people of what is today Okinawa Prefecture and restoring the independence of the Ryukyus.

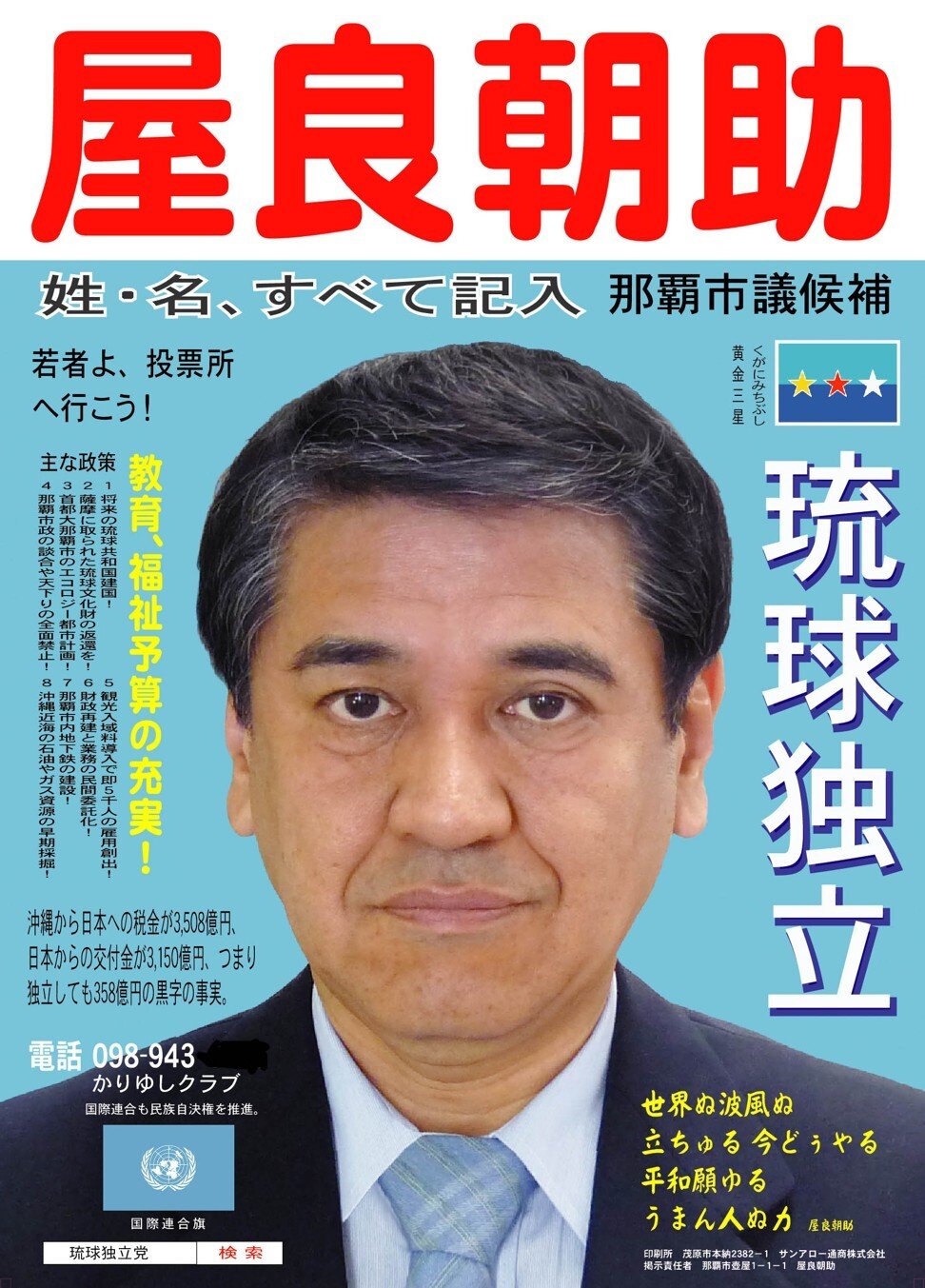

Chosuke Yara, the head of the Ryukyu Independence Party, concedes he has some way to go before he can convince a majority of voters to back his vision of the islands’ future, but he and his supporters have mapped out economic, social and security policies that could swiftly be implemented and would ensure the islands prosper as soon as they are free from the direct control of Tokyo. And he is in it for the long run.

“I joined the Ryukyu Independence Party when it was founded in May 1971, but I was already a firm believer that we should once more be free,” he told This Week in Asia, underlining his long-standing credentials by pointing out that his predecessor, King Sho En, “had ruled more than 300 years before George Washington became the first president of the United States”.

Born in Naha, the largest city in Okinawa, 68-year-old Yara owns a company that prints T-shirts. He divides his time between his hometown and Chiba for business reasons, but his spare time is spent devising policies and planning electoral strategies – and he counts off his fingers the reasons the Ryukyu Kingdom should once again be independent.

“The people of Okinawa have a strong anti-war feeling, primarily because we were forced to make great sacrifices during World War II,” he said. “Many Okinawans were forced to fight with the Japanese and lots of civilians were slaughtered by Japanese troops. In my opinion, the Japanese considered Okinawans to be inferior foreigners and they killed them without hesitation.

“If there is another war, I believe Japan would sacrifice Okinawans in exactly the same way. That is why they have concentrated the US military bases in Okinawa instead of having them on the Japanese mainland. If war were to break out, it is highly likely that US bases – and the people of Okinawa – would become the target of nuclear attacks.”

An independent Ryukyu would be free to make its own security alliances and conduct diplomatic negotiations that would be in the islands’ best interests, avoiding war at all costs, Yara said.

Free from Tokyo’s control, islanders would also “regain the consciousness of proud Ryukyuan people”, with the original language reintroduced at schools and new history books replacing those imposed on the prefecture by the central government – which infuriate Yara by their claims the Ryukyu Kingdom was simply assimilated into Japan.

Independence activists insist the Ryukyus were “illegally annexed”, a process that began with an invasion by troops of the feudal domain of Satsuma in 1609. A system of limited autonomy remained until 1879, when the kingdom was abolished and Okinawa Prefecture was declared. King Sho Tai was forcibly exiled to Tokyo and the Meiji Period government increasingly suppressed Ryukyuan ethnic identity, traditions and the language while carrying out a comprehensive assimilation programme.

Yara said the once wealthy islands were reduced to poverty by taxes imposed by Tokyo, national treasures in Shuri Castle were stolen and people were punished for speaking Ryukyuan. But the islanders’ experiences during the war – the brutality of the Japanese defenders is well documented – has lingered, he added.

“My father survived the battle of Okinawa but virtually all his classmates were killed,” Yara said. “I remember him drinking, and when he would drink he would always look sad.”

Yara’s party advocates an independent Ryukyu being tax-free or having a very low tax rate to attract corporations from around the world – “Like in Hong Kong, before,” he said – while domestic industry would focus on tourism, exports of high-end agricultural and marine products and the promotion of Ryukyuan culture and art.

An independent Ryukyu would also be free to exploit vast amounts of offshore natural resources – studies suggest the waters around the islands are high in hydrothermal deposits – while energy would come from plentiful supplies of solar and wind power.

Yara also envisages the strategically located Ryukyu Islands serving as the base for a disaster response organisation that could be swiftly dispatched to anywhere in the Asia-Pacific region, while he also has plans for specialist hospitals and rehabilitation facilities that would take advantage of the natural environment and be free for children from around the world.

01:59

In the heart of South America – Okinawa, Bolivia clings to Japanese root

Even more ambitiously, he believes it will be possible to defuse many of the territorial and security-related tensions constantly simmering below the surface in the region by creating what he describes as a “recreation centre” in Okinawa that would welcome warships and military personnel from every nearby nation, including North Korea, for regular get-to-know-you meetings.

In terms of an independent Ryukyu’s allies, Yara is keeping his options open. Certainly the US and Japan are possibilities, although he insists the US bases will need to go or the US will have to start paying rent, but he is not ruling out working with China, Russia or other “partners”, depending on the situation.

This open-minded approach to a future Ryukyu’s security needs has led to accusations the party is in part funded by Beijing, which is keen to prise the islands away from both Japan and the US as it seeks to expand its influence and power in the region. Nationalists flatly deny that accusation on the grounds they have no intention of exchanging one colonial overlord for another.

The biggest obstacle to Yara’s ambitions, inevitably, is Tokyo – although independence is not an absolute impossibility, according to Go Ito, a professor of politics at Meiji University.

“If there was sufficient support then a referendum on independence could be called, but there is a tremendous amount of risk attached to voting to leave Japan,” he said. “The biggest issue would be the sudden loss of financial support that is provided by Tokyo, and Okinawan people would have to accept their economy would suffer and their standard of living would inevitably go down.”

Construction is still the largest employer in the prefecture, he said, and that would dry up immediately if residents turned their backs on Tokyo. The other sources of revenue for the islands – agriculture, fisheries and tourism – would not be able to immediately pick up the slack.

“Independence activists everywhere are always rosy about how life will be after they win their freedom, but I think the people of Okinawa know how closely they are financially reliant on Tokyo,” Ito said. “Independence activists appeal to the public’s heart over their heads, and that certainly appeals to some, but I think that at the final reckoning, people would realise they were better off with keeping things as they are.”

There is a degree of support for independence, although polls suggest it has declined. A study in 2005 indicated 24.9 per cent of residents were in favour of independence, although that had declined to 20.6 per cent in 2007, while a poll by the Ryukyu Shimpo newspaper as recently as 2016 found just 2.6 per cent favoured full independence, while 15 per cent wanted a federal framework with local authority equal to that of the national government in terms of diplomacy and security.

The biggest problem that we face is that the general public does not know the history of Okinawa because of the history we are taught in school

In November 2014, Yara stood in the election for the Naha city council, winning just over 10,000 of the 140,000 votes cast. In July 2017, however, he won a mere 526 votes, although he attributes that disappointment to a crowded field of no fewer than 67 candidates. He remains upbeat about his campaign’s prospects.

“The biggest problem that we face is that the general public does not know the history of Okinawa because of the history we are taught in school,” he said. “Okinawans have been trained to think of themselves as Japanese. We have to be active in disseminating our information and we have to be patient. But I think our campaign is working. We are gradually winning recognition and support. I truly believe that we can be self-sufficient and independent.”