The Philippines wants to outlaw child marriage. But in Muslim-majority Bangsamoro, change will be hard

- Proposed legislation banning marriages for children under 18 conflicts with the country’s Code of Muslim Personal Laws, under which girls as young as 13 can be married

- Experts say decades of war in the Bangsamoro region have caused an increase in child brides, while long-held cultural practices could prove difficult to shift

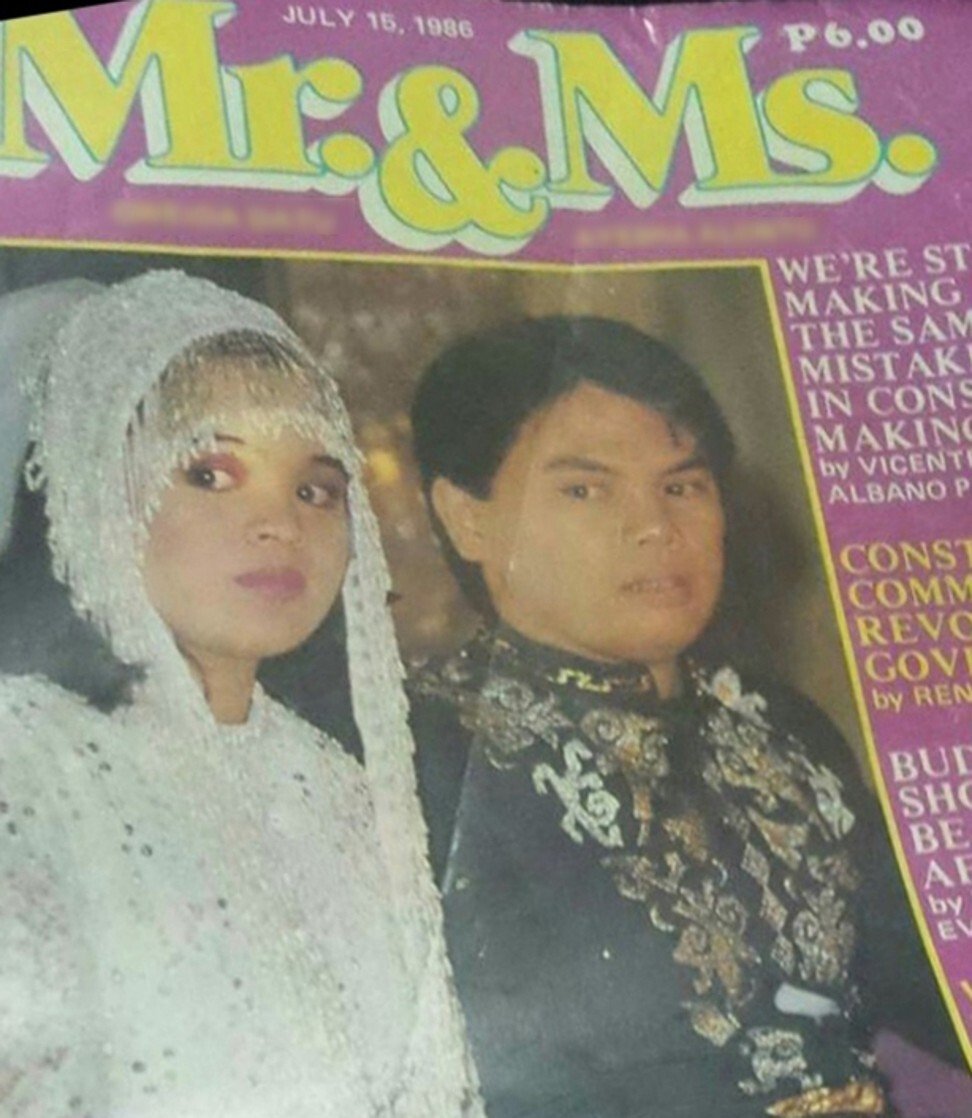

Ayesha Merdeka wants child marriages to be a thing of the past. They aren’t an abstract concept to her – they are the reality she has lived with for more than three decades after her grand wedding at the age of 15 made a splash in newspapers and magazines across the Philippines.

She is a member of a politically influential clan in what is now the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) – where most of the 3.8 million residents are Muslim, in contrast with the rest of the predominantly Catholic country – and hers was the first Muslim Maranao-style wedding to be held in the capital, Manila.

Ayesha’s father, Abul Khayr Alonto, was the founding Vice-Chairman of the Moro National Liberation Front. He recruited Nur Misuari, who became the group’s leader, into the rebel movement. Her father, who was appointed by President Rodrigo Duterte as chairman of the Mindanao Development Authority in 2016, died last year.

At the time of Ayesha’s wedding, then-president Corazon Aquino was seeking peace talks with the rebels. Several foreign diplomats from the US and Russian embassies attended the ceremony. But little did the guests know, the bride had no choice but to marry.

It was like having “an invisible gun on your head”, Ayesha, now 49, told This Week in Asia. She clarifies that she wasn’t forced into marriage – it was “more like [being] indoctrinated into the idea that marriage was a decision made by the elders. It’s like your mind was conditioned from the beginning that that area of your entire life is going to be decided by them.”

Ayesha, who still lives in the BARMM, said suitors, including those from abroad, began circling when she was 13 years old and still “boyish looking”. But her father put his foot down and said she had to marry within the clan.

He warned her that if she committed “a moral mistake, then I will make an example [of you] to the Bangsamoro women”, Ayesha recalled.

“The one thing that really held me after he said that,” she said, was that “his voice became imploring as he said, ‘Please don’t make me do that to you’. The voice is still at the back of my head but I trusted that my dad would choose the best man among the Moros [for me].”

‘AN ACT OF CHILD ABUSE’

According to Girls Not Brides, a partnership of civil society organisations committed to ending marriages involving children, 15 per cent of Filipino girls were married before their 18th birthday, and 2 per cent were married before the age of 15.

Boys in the Philippines are less likely to enter into child marriages – in 2017, there were 32,000 brides between the ages of 15 and 19, four times the number of grooms, according to official figures. Part of the problem, Girls Not Brides points out, is the trafficking of women and girls from rural regions to urban cities, as well as forced marriages.

Another issue the group identifies is religion. Most registered child marriages in the Philippines take place in the BARMM – which is in Mindanao, the country’s second-largest island – where women can marry at a very young age under the 1977 Code of Muslim Personal Laws.

That legislation, enacted through a decree from then president Ferdinand Marcos, set the marrying age for Muslims at 15, but provided an exception – girls can be married as young as 13, provided they are menstruating, and a wali, or guardian, petitions for the marriage.

Last month, Senate Bill 1373, which criminalises marriages between an adult and a minor – defined as a person under the age of 18 – was unanimously approved by the Senate. A similar measure, House Bill 1486, has bipartisan support and is awaiting a nod from the House of Representatives that is expected to come by next year.

The Senate bill, which calls child marriage “an act of child abuse as it debases, degrades and demeans the intrinsic worth and dignity of children”, aims to punish relatives, guardians and those who facilitate such marriages with a fine of not less than 50,000 pesos (US$1,037) and between six and 12 years in jail, as well as the “loss of parental authority” over the victim.

Its main sponsor, Senator Risa Hontiveros from the opposition Akbayan party, told local media after the vote that the issue of early and forced child marriages was “a tragic reality for scores of young girls who are forced by economic circumstances and cultural expectations to shelve their own dreams, begin families they are not ready for, and raise children even if their own childhoods have not yet ended”.

However, even if the law is passed, realities on the ground will make its implementation difficult, according to Muslim rights activists in the Philippines who are seeking to end the practice.

A senior member of the National Ulama Conference of the Philippines, speaking on condition of anonymity, said he did not think the proposed child-marriage law was “automatic for Muslims” given the concurrent existence of the Code of Muslim Personal Laws.

He revealed that there was an ongoing discussion between the ulamas on the conflict between the Code and the impending congressional legislation banning child marriages.

“We are trying to reconcile the two views – the Code says 15 [is the marrying age], while the [proposed Congress legislation] says 18,” he said, explaining that some Islamic scholars put the age of marriage for women “from the time she starts menstruating, but the Koran itself has no provision regarding that”.

‘IT STOPS WITH ME’

Experts say decades of war in the BARMM – including in the province of Magindanao, and the 2017 battle to retake the city of Marawi from Islamic State-affiliated militants – have made the region the poorest in the country, and caused a spike in the number of child brides.

“It alarmed us,” said Sittie Jehanne Mutin, former chair of the Regional Commission on Bangsamoro Women, of the rise in child brides among tens of thousands of internally displaced persons or refugees due to the protracted war between government troops and the separatist Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). The rebellion officially ended last year after a peace deal that saw MILF rebel commanders become administrators of the newly formed BARMM.

Mutin said the war had taken a toll on families taking care of young girls, and marrying them off meant fewer mouths to feed, while it was also a way of preventing possible sexual abuse since strangers were crammed together in refugee camps. The really poor families did not mind even if the groom was decades older, she said, so long as “they can afford the dowry”.

She pointed out that the situation could not be addressed simply by an outright ban since there were multiple laws that existed and were applicable, including international Islamic law; Philippine sharia law, as outlined under the Code of Muslim Personal Laws; as well as the various traditional and customary laws observed by the 13 Muslim-majority ethnic groups in Mindanao.

Ordinarily, Mutin added, arranged marriages were a custom with built-in protective mechanisms. For instance, “parents will never force a child to marry without really looking at the advantages for their own daughter. That’s usually very high on their list.”

This community aspect is also evident to columnist and peace advocate Samira Gutoc, who took part in drafting the Bangsamoro Basic Law for the BARMM. She said there were many instances when young couples were made to abstain from sexual relations until the girl reached “the age of maturity” or started menstruating.

“The purpose of marriage is not just to strengthen power relations; it also provides social protection [and] protection against family vendettas,” Gutoc said, pointing out that some marriages were arranged between clans after slights were exchanged so as to prevent the clans from warring.

She was almost made to marry young herself, and recalls “running away” to show her refusal to do so – following in the footsteps of her mother, who had flatly rejected the notion after seeing her older sister marry around the age of 13 and drop out of school to bear children.

As for Ayesha, when asked about her own marriage, she explained that there were some arranged marriages that worked because “Islam emphasises duty over individual rights”.

“It gets more complex when you really look at the culture,” she said. “I chose to be happy every day. There are a lot of things to be grateful for.”

Her husband visited and wooed her daily for three months before their wedding, keeping to a condition imposed by a stern aunt. “My aunt was crying throughout her wedding day because [she had only seen her husband] on that day.”

Ayesha, whose early marriage did not stop her from finishing a history degree and teaching for nearly four years in Libya, said Filipino Muslim women were “far more empowered” than those in the Middle East. In Libya, she would be summoned by the school head to “stop your revolution” about Muslim women’s rights.

It’s a revolution she continued at home. None of her three daughters – who are still single in their 20s and 30s – were forced into arranged marriages, she said, and her eldest son married for love.

“It stops with me,” said Ayesha, whose second given name, “Merdeka”, means freedom.