Breakdancing is going to be an Olympic sport. Will it give the South Korean scene a hand(stand)?

- Set to feature at the 2024 Paris Games, Korean B-boys and B-girls are hoping the inclusion will revitalise the country’s breakdancing culture

- While the country is ranked No 2 in the world and its crews and stars are renowned overseas, celebrity status at home is harder to come by

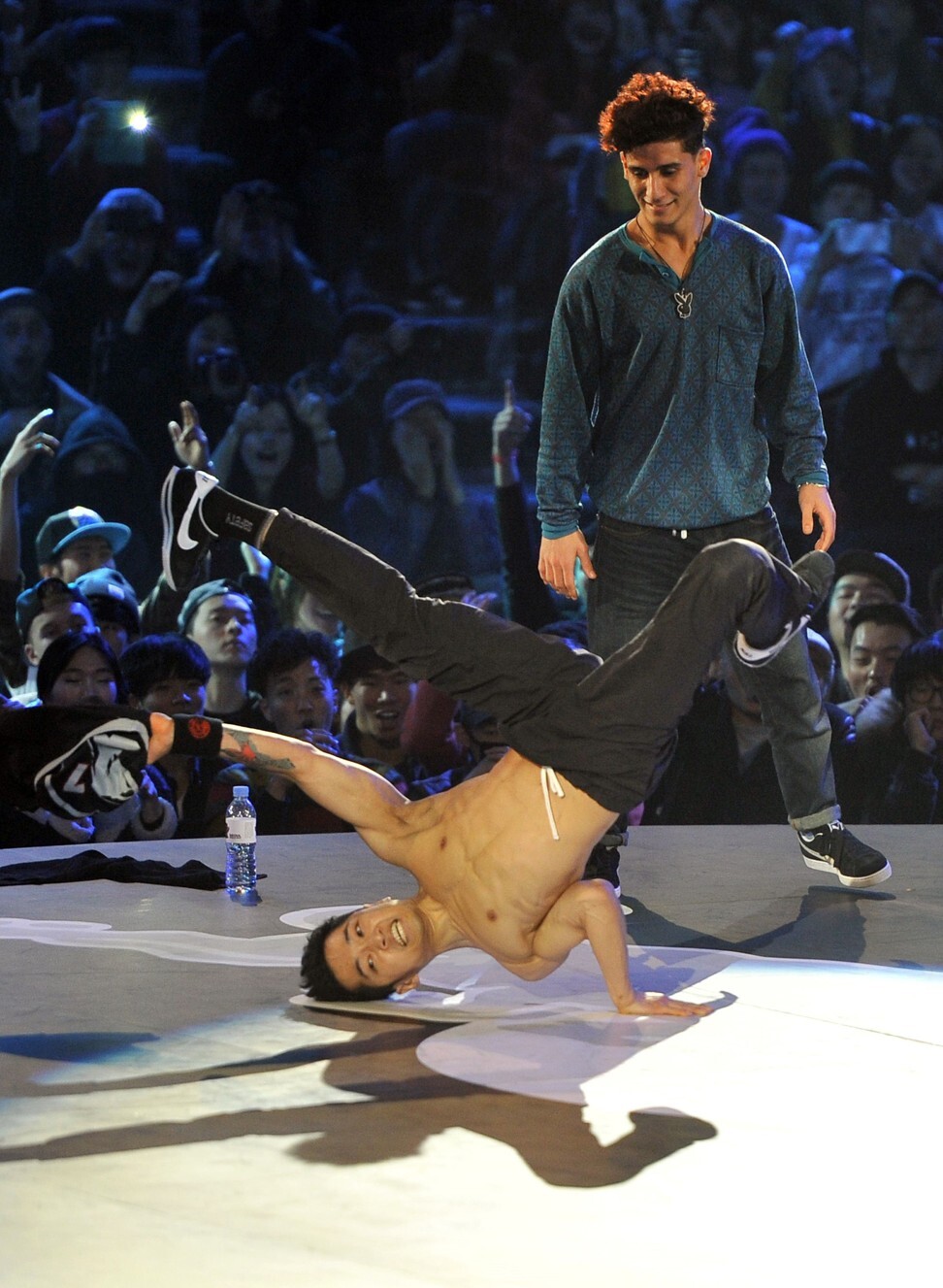

Breakdancing, for obvious reasons, has been one of the activities sidelined by the Covid-19 pandemic. Also known as “b-girling or b-boying”, its culture is all about rambunctious street performances and heated battles between crews showing off their windmills, airborne kicks and handstand freezes.

Dance studios across South Korea – a country traditionally hailed as being on top of the breakdancing world, along with the likes of the United States, France and Japan – are devoid of music and activity as the disease continues to spread. But with the International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) announcement earlier this month that competitive breakdancing would be included at the 2024 Paris Games, anticipation in the country is high.

Having already been featured at the 2018 Youth Olympics in Buenos Aires, the IOC decided that the sport would be added to the main competition alongside skateboarding, sport climbing and surfing in an attempt to connect with younger audiences after the declining viewership of previous Olympic Games. To South Korean crews, however, this isn’t just a chance to win a gold medal, it’s an opportunity for the revitalisation of Korean breakdancing culture.

“B-boys would half-jokingly talk with each other about performing at the Olympics in front of crowds of thousands one day,” says Flex, the leader of the Fusion MC crew, one of the front runners to represent the country in 2024.

Fusion MC – currently ranked the 21st best crew in the world by Bboyrankingz, the community’s leading website – last year became an official arts organisation of the city of Uijeongbu, just north of Seoul. Their dance studio has a meeting room filled with trophies and medals from competitions around the world, including a 2013 win at Battle of the Year, also known as the World Cup of breakdancing.

Many of the younger members, in fact, started breaking after seeing Flex’s amateur dance club performing in the city centre, and Fusion MC’s partnership with Uijeongbu has given the crew a financial backbone at a time when dancers have found it hard to eke out a living due to restrictions on stage performances.

“We are one of the few crews that are lucky enough to have financial support to continue practising in our dance studio for six hours a day, six days per week,” says Flex, who at 32 is the oldest member of the crew.

Before the pandemic, Fusion MC would collaborate with organisations in the city for street performances every weekend, and its members also received national recognition for competing on the television show Korea’s Got Talent. “Every time we were in the public eye, we were trying to make breakdancing more mainstream and approachable to the masses,” Flex says.

Even though South Korea is currently ranked No 2 in the world – behind the US – and is home to some of the planet’s most well-known breakdancers, the country’s B-boys and B-girls don’t have the celebrity status afforded to many others in the local entertainment industry.

“Breakdancing is not popular in South Korea,” claims Kim Geun-so, a founding member of People Crew, the country’s first B-boy crew, who is better known in the breakdancing community as Jerry. Now a professor at Seoul Hoseo Art College, the 44-year-old explains that local crews are much more known abroad than at home.

The heyday of South Korean breakdancing was in the 2000s, after Expression Crew became the first crew from the country to win Battle of the Year in 2002. Korean crews won five of the next 10 competitions, but have only won the annual event twice since.

“The synergy effect from competing for the top spot in a country with so many talented crews created the basis of South Korea‘s booming years,” Kim says. “But even after winning numerous international competitions overseas, Korean B-boy crews would come back home to see that nothing had changed with regards to their popularity or prestige other than the fact that they had a few more trophies to add to their collection.”

Because of this, he says, South Korean children want to become “K-pop stars who are living lavish lives and are constantly in the spotlight, not B-boys who dress in street clothes and practice in run-down dance studios”.

Kim compares the current state of Korean breakdancing, which is dominated by dancers in their 30s, with countries such as France and Japan, which have developed youth training programmes that have produced some of the world’s best young breakdancers.

However, he does see some hope at home, with some of the top crews becoming more professional and systematic in their management. Besides Fusion MC, Jinjo Crew – the No 3-ranked crew in the world, headed by the No 2 ranked B-boy, Wing – is starting to change the image of Korean breakdancers. In addition to a partnership with the city of Bucheon, the crew boasts sponsorships from the likes of Nike and Red Bull.

And inclusion at the Olympics is another opportunity to raise the profile of South Korea’s home-grown breakdancers.

Leon is Fusion MC’s best hope for the Paris Games. The 27-year-old is ranked No 69 in the world, but he has a track record of success in events such as the Red Bull BC One Asia Pacific Finals in 2015 and, three years later, the same event’s cypher, or unrestricted freestyle, version in South Korea.

“If practising in the studio was all that B-boys were known for, I’ve added some [weapons] to my training regime these days,” Leon says. “I’m approaching the road to the Olympics like any other athlete, going to the gym and the rehabilitation centre to prepare my body for the toughest competitions.”

However, there are those who worry that breakdancing is on its way to becoming more like a sport than an art form.

Kim, formerly of People Crew, also currently teaches breakdancing, after a bout of injuries saw him withdraw from competitive breakdancing. He still remembers the first time he saw a B-boy perform a “Nike freeze” on television more than 30 years ago: a handstand with one leg stretched and the other bent, mimicking the Nike logo.

“After I saw breakdancing for the first time on the American television show Soul Train, I started to visit clubs that were known to have a lot of Americans and hip-hop dancers,” he says. “We got into breakdancing simply because it looked cool and because it was art that we wanted to continue perfecting.”

However, Kim says it is equally important that any type of art needs to be known and liked by a lot of people: “What’s the use if no one watches our art?”

He sees the Olympics as a possible avenue to a second boom in Korean breakdancing, reminiscent of the glory days in the early 2000s when the world’s top-ranked crews all hailed from South Korea.

“Success in a global event like the Olympics may potentially change the minds of parents and kids who might later want to become a B-boy or b-girl representing South Korea on the biggest stage in the world.”

For more great stories on Korean entertainment, artist profiles and the latest news, visit K-post, SCMP's K-pop hub.