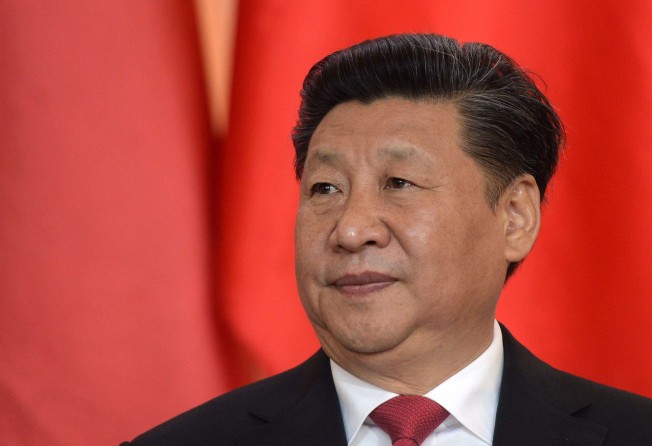

How even as ‘the core’, Xi faces resistance from China’s local officials

Two high-level meetings broadcast to the public in recent days have showcased the strengthening power of the undisputed ‘party leader’

If there’s one buzzword that encapsulates Chinese politics in 2016 and the year ahead, it has to be He Xin, or “the core”.

Last January, the Communist Party’s leadership for the first time publicly urged its 88 million members to embrace the “consciousness of the core”. Then in November, the party’s central committee bestowed the designation “core of the party centre” on President Xi Jinping ( 習近平 ).

No other Chinese leader in recent decades has concentrated so much power in his hands in such a short period of time. In just four years, Xi has accumulated sweeping control over the party, the state, military and economy, elevating him to the ranks of Mao Zedong (毛澤東) and Deng Xiaoping ( 鄧小平 ).

But Xi’s rise as an undisputed leader has also beentested by the entrenched tendency of local officials to disregard the decrees of central authorities in distant Beijing – a phenomenon succinctly summarised in the traditional Chinese saying: “The sky is high and the emperor is far away.”

Both Xi’s strengthening power and the issue of local officials were made more evident after the details of two recent meetings of the Politburo and its Standing Committee were splashed across national media – a very rare departure from standard protocol.

On Tuesday, national television devoted 16 minutes of its 30-minute prime time news programme to reporting the two-day Politburo meeting, chaired by Xi. As the camera panned across the 25-member meeting, each of China’s most powerful officials could be seen reading from prepared speeches and pledging their allegiance to Xi as the core of the party leadership, which the members saidconcerned the fundamental interests of the party and the nation, upheld party unity, the authority of the party centre and long term developments of the party and the country.

Xiemphasised strict discipline and unconditional loyalty as important guarantees for a centralised and unified party, and urged Politburo members to take the lead by complying with rules and regulations.

As Politburo meetings are generally closed-door events, the decision to broadcast the session was a clear sign of Xi’s expanding influence.

Much has been written in overseas media about Xi’s political ambitions since he was designated as the core of the leadership. But less has been reported on the deeper reasons for the designation and its wider implications.

It was not just his capability and personal ambition that led Xi to amass so much power so quickly. His rise was particularly helped by the widespread yearning for a stronger central authority following the ten-year reign of Xi’s predecessor, Hu Jintao (胡錦濤), from 2002 to 2012. During that decade, the mainland’s economy grew strongly, but Hu’s weak leadership contributed torampant official corruption and other political and social ills.

This gave rise to the saying that central government decrees do not make it out of Zhongnanhai, the downtown compound in Beijing where top leaders live and work. Local officials were left to merely pay lip service to such decrees.

More importantly, as Chinese officials readily admit, reforms to transform the economy have entered into “the deep-water zone”, which has prompted calls for a stronger central leadership to overcome resistance from local officials and tackle long-standing issues such as endemic pollution, imbalanced regional development, income disparity and social injustice.

History has also shown that whenever the central authority was strong, the country has tended to remain stable and its economy has grown steadily whereas a weak centre would lead to instability.

But even with Xi’s leadership, getting local officials to comply with the central government’s wishes has proven a daunting task. This explains why Xi chaired a session of the Politburo Standing Committee just 10 days ago to discuss punishments for nearly 140 local bureaucrats and officials of two steel companies found guilty of colluding to circumvent one of Xi’s economic priorities

Since late 2015, Xi has pushed for supply-side structural reforms to resolveimbalances in the economy bycutting industrial capacity and financial leverage, among other measures.

As a result, the government moved to reduce steel production capacity by 45 million tonnes and coal by 250 million tonnes in 2016 – targets that officials claimed were met ahead of schedule.

In reality, however, local officials have remained resistantto such directives. According to a Xinhua report on the Standing Committee meeting, numerous steel companies in Jiangsu ( 江蘇 ) and Hebei ( 河北 ) have openly flouted central government’s wishes by producing banned and substandard steel products with the help of local authorities. This forced the central government in November to send investigation teams to gather evidence.

Xi was believed to have called the meeting to discuss punishments for the officials, who included two deputy provincial governors from Jiangsu and Hebei who were held accountable for their oversight and failure to step in.

Meetings of the Politburo standing committees are rarely publicised, but on the few occasionsthey are, they usually focus on party and policy issues, responses to major natural disasters or industrial accidents.

By making the latest meeting public, Xi clearly saw the blatant disregard of local officials as a direct challenge to the central authority and intended to use the punishments as a stern warning to others. And with the central government vowing to make deeper cuts to industrial overcapacity in 2017, bringing local officials into line will be an interesting test of theauthority. ■

Wang Xiangwei is the former editor-in-chief of the South China Morning Post. He is now based in Beijing as editorial adviser to the paper