Beijing’s tight grip on economy leaves tycoons on a tightrope

The exoneration of Wumart founder Zhang Wenzhong raises hopes of a new approach to private enterprise in China. But opaque policymaking and the government’s stranglehold on the economy stand in the way of true change

By some estimates, China already has more US dollar billionaires than the United States and is gaining new ones at a faster rate than any other country. Many of these billionaires sit on the National People’s Congress, the country’s legislature, and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, the national advisory body, where they rub shoulders with senior government and party leaders, seeking opportunities to shape the direction of the world’s second-largest economy.

Like elsewhere in the world, mixing business with politics has pitfalls and even dangers. This is particularly so in China where, as the government’s stranglehold over the economy is still immense and the policymaking process opaque, most of them have little choice but to seek political patronage for preferential treatment and to expedite deals, among other things.

So their fortunes and even their well-being are subject to political whims. Strong political protection may make them richer but falling out of political favour may easily break them, leading to disgrace, jail or even death.

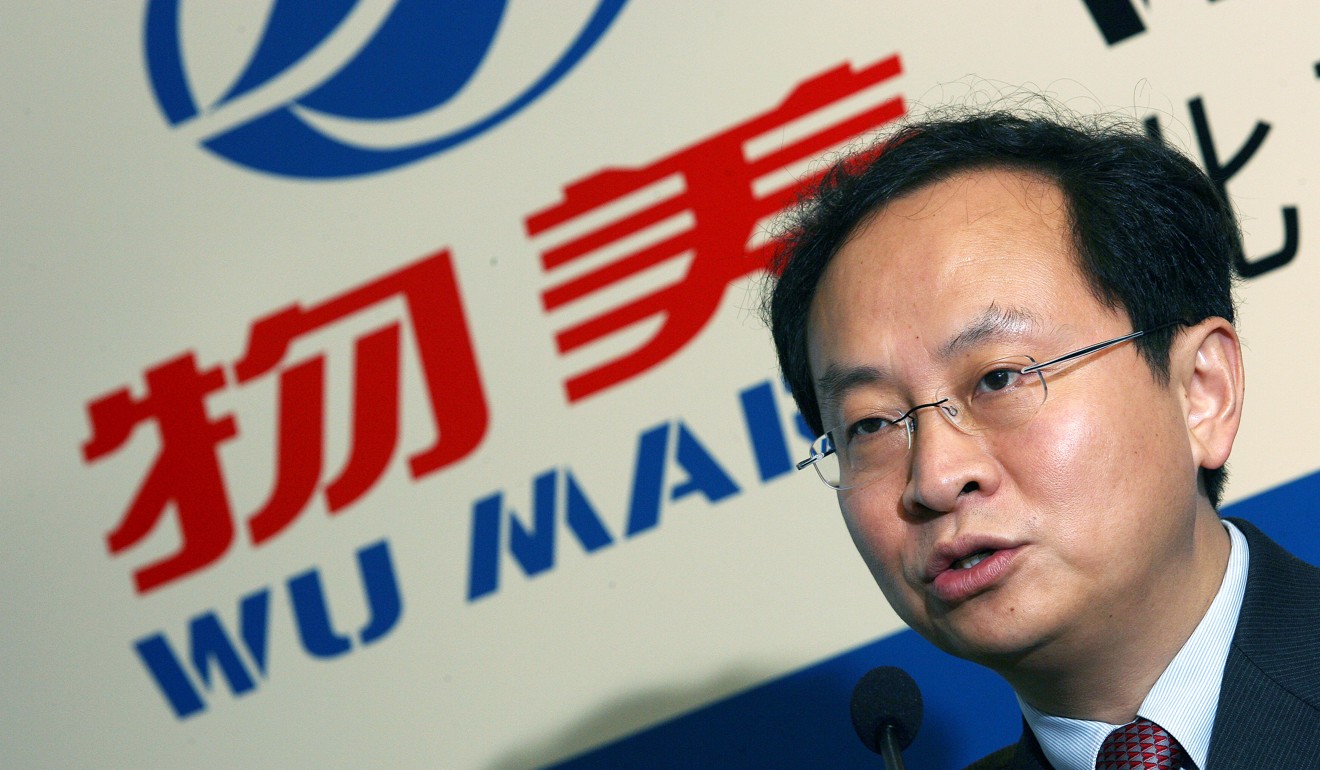

That explains why the announcement by the Supreme People’s Court just over a week ago that it had exonerated a supermarket tycoon jailed for fraud and embezzlement 10 years earlier caused such a stir, particularly in China’s embattled private sector.

On May 31, the court took the unusual move of broadcasting live on television the ruling that cleared Zhang and promised compensation for his jail time.

The state media hailed Zhang’s acquittal as a landmark case signalling China’s determination to better protect the legitimate rights of private businessmen, particularly their property rights.

Speaking to official media, Zhang was grateful to the Central Government for clearing his name and said “the correction will inject a new driving force into the development of private enterprise”.

Let’s hope so. This year marks the 40th anniversary of reforms and opening up launched by the late paramount leader Deng Xiaoping and China is preparing elaborate commemorative activities and vowing bolder moves to propel the economy to a whole new level.

Over the past four decades, many private businessmen have become fabulously rich as the private sector now contributes more than 60 per cent of China’s GDP and provides about 80 per cent of jobs. Yet they remain on precarious ground, subject to political whims, arbitrary convictions and being forced to bribe officials.

Back in the early 1980s, a landmark case involved a small-time vendor from Anhui who peddled sunflower seeds. Nian Guangjiu, who employed more than 100 workers, used sales promotions to market his products and made one million yuan in three months – an astronomical figure at that time. His entrepreneurship led him to be convicted three times by local courts on various trumped up changes, though he was exonerated after an intervention by Deng. In the end, the Nian case proved a watershed in China’s efforts to encourage development of the private sector as righting a wrong case was far more effective than a dozen government documents on educating people about the issue.

But violations of private property rights and the harassment of entrepreneurs have continued, not least because of “original sins” – the many businessmen in the early years of reform who were forced to breach laws or regulations later considered outdated and rescinded.

There have been many cases in which local authorities have tried to settle old scores by going after certain businesses, dampening investment sentiment.

Moreover, as their businesses grow, entrepreneurs have been forced to seek political patronage from officials because of the opaque decision-making process.

That set up the fall for Zhang, the supermarket tycoon. Graduating from Stanford’s School of Engineering, Zhang returned to China and launched the first Wumart store in Beijing in 1994. Ten years later his chain of stores accounted for one third of Beijing’s retail market. In 2003, Wumart became China’s first supermarket chain to list in Hong Kong’s main bourse. Alongside the expansion of his business, Zhang secured strong support from Liu Zhihua who later become vice-mayor of Beijing. Liu flew to Hong Kong for Wumart’s listing ceremony.

After Liu was investigated on suspicion of corruption in 2006, a number of businessmen seen as close to Liu were also probed, including Zhang that same year. But a thorough investigation turned up no evidence of impropriety between Zhang and Liu.

In 2009, a Hebei court convicted Zhang on three charges unrelated to Liu’s case and now the Supreme Court has ruled those charges were based on insufficient evidence and incorrect application of law. Zhang spent seven years incarcerated – from 2006, when he was held for questioning, to 2013, when he was released after two sentence reductions. He spent another five years clearing his name. Despite his imprisonment, his business empire has survived and Forbes estimates his personal wealth to be US$2.7 billion.

Over the past few years, leading tycoons including Xiao Jianhua of Tomorrow Group, a financial conglomerate, and Ye Jianming, the founder of one of China’s largest oil companies, have disappeared from public view and have presumably been under investigation. They are likely to emerge at some point for criminal trials that will end with lengthy jail sentences.

That is what happened to Wu Xiaohui, chairman of one of China’s biggest insurers and the owner of the Waldorf Astoria hotel in Manhattan, who last month was jailed for 18 years on charges of illegal fundraising and embezzlement. These tycoons may be accused of various crimes, but they have one thing in common – strong connections with senior officials who helped them to achieve their vast wealth.

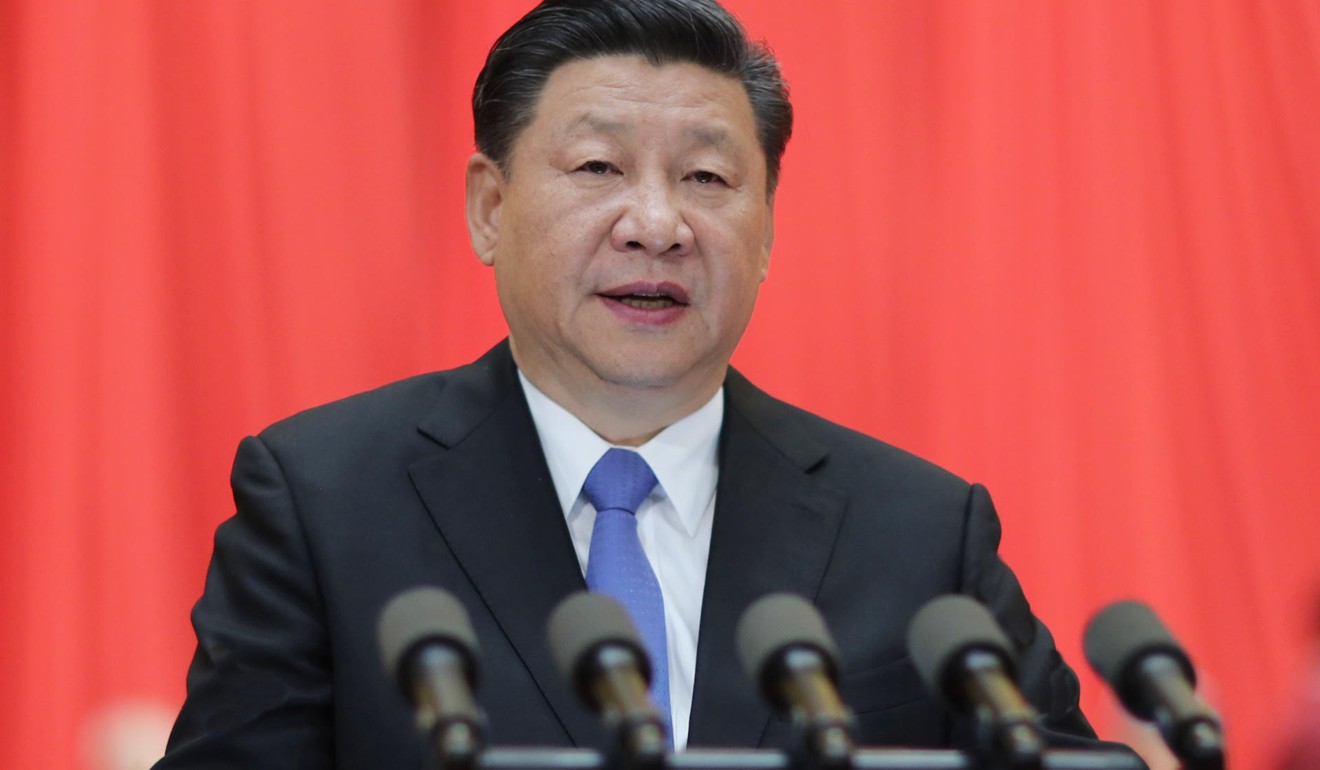

Vowing to tackle rampant collusion between businessmen and officials, Xi in 2016 began preaching about a new type of relationship between the two – one characterised by “honesty and sincerity”. But it will be hard for honesty and sincerity to take hold if the government does not loosen its stranglehold on the economy or rethink its opaque decision-making. ■

Wang Xiangwei is the former editor-in-chief of the South China Morning Post. He is now based in Beijing as editorial adviser to the paper