With China no longer aboard, Mahathir opens new chapter in Saga of the Malaysian People’s Car

The prime minister’s plans to revive Malaysia’s national car project is about more than just an automobile: it is about face, and one man’s enduring obsession with legacy

Malaysia’s newly elected Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad has raised the possibility of a new national car project, putting behind him the mixed fortunes of his previous initiative, Proton, launched over three decades ago.

“We need to go back to the idea of a national car,” he announced at the 24th Nikkei Conference in Tokyo on his first foreign trip since his election last month. “Our ambition is to start another national car, perhaps with some help from our partners in Southeast Asia … we want to access the world market.”

His announcement that Malaysia was seeking new automotive partners and that Proton with its 49.9 per cent Chinese holding was no longer the Malaysian national car, made so soon after his election, suggest he is wasting no time in writing a new chapter in Malaysia’s automotive history – a history largely down to him.

Malaysia, he said, has “most of the skills and technologies in regard to the design and production of a new car” thanks to two decades of cooperation with Japan’s Mitsubishi Motors. “There are certain parts of a car which are extremely expensive to develop. We will want to source some of those expensive parts from other countries, including of course from Japan.” China was pointedly not mentioned.

Mahathir hopes to produce a car which will conform to the Euro-5 or Euro-6 emission standards to access the world market. “We see in Silicon Valley there are a lot of new ideas that have come up, making use of IT and sensors used in building driverless cars.”

Mahathir’s remarks about a new national car provoked scepticism among industry analysts and on social media: citing the difficulty in penetrating a highly globalised market, the precedent of Proton and the fact that Proton and its nearest indigenous competitor Perodua have lost market share to foreign competitors. But the sceptics are missing the point. This is not about the globalised market, or about Proton, or Perodua. This is not even about tax-free access to the 623 million strong Association of Southeast Asian Nations bloc and multi-state cooperation in producing environmentally friendly hybrid power units. This is about history, and one man’s place in it.

So what about the history? The first Malaysian National Car Project, as it was known, was conceived in 1979 by Mahathir, approved by the Cabinet in 1982 and established as Proton – Perusahaan Otomobil Nasional Berhad – in 1983. Mahathir thus became probably the only head of state to found and head a national automobile company.

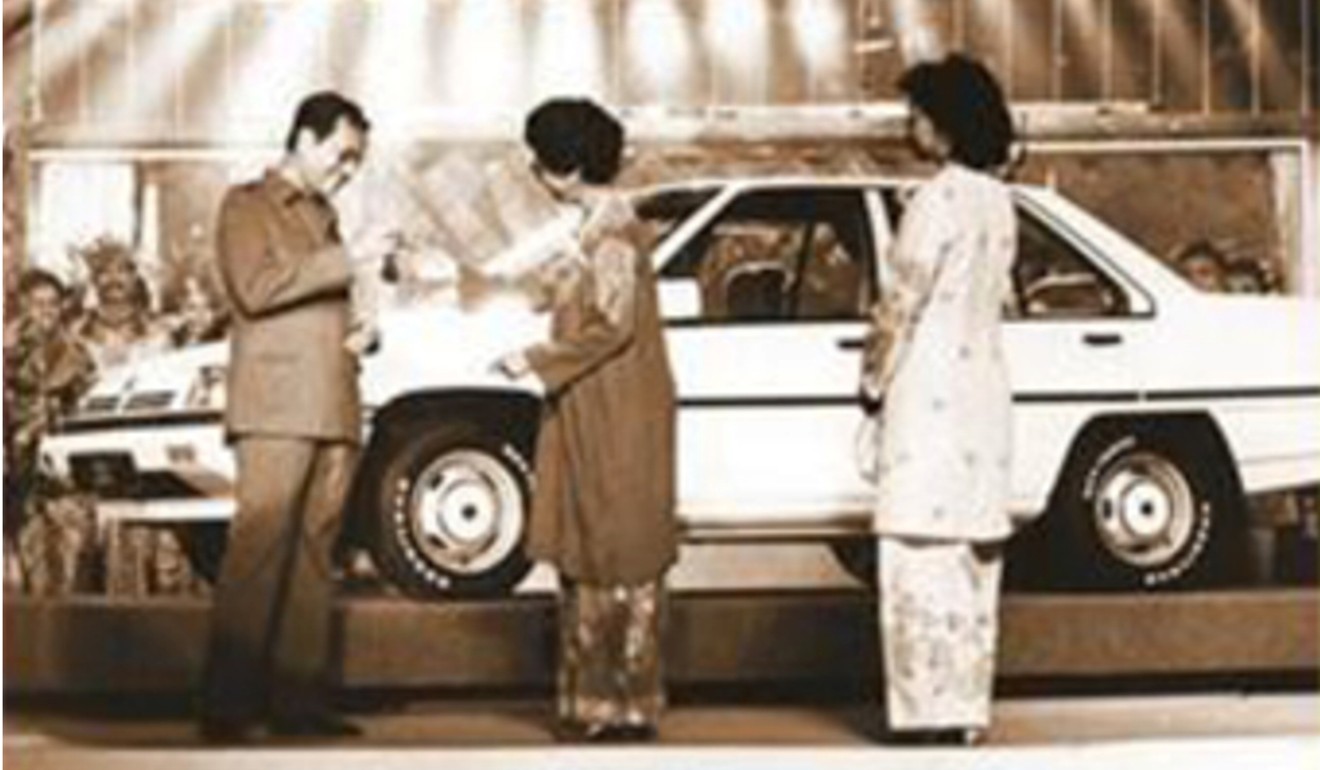

In 1985, he opened the Shah Alam plant: “The Proton Saga,” he declared of the first model, “is more than just a quality automobile. It is a symbol of Malaysians as a dignified people.”

The name derived from a Malaysian tree denoting resilience and indigenous identity.

Proton’s share of the domestic market for cars below 1,600cc peaked at 74 per cent, but demand outstripped supply and the government was losing 35,000 Malaysian ringgit (US$15,000 at the time) on each Saga sold. Following a locally mismanaged export foray into the United States, in 1993 the company came back under Malaysian management. Proton introduced new models and made inroads into European markets, but the entry of the privately owned Perodua, with superior engineering from Toyota, into the domestic market ended the state-owned monopoly of Malaysian auto production.

The second half of the 1990s saw competition and losses increase at home and abroad. Foreign dealerships deserted Proton and the marque became synonymous with poor quality for the buyer and poor returns for the taxpayer. In 2012, Proton was privatised by Malaysian conglomerate DRB – HICOM. With production slipping again by 2015, the government approved a soft federal loan of 1.25 billion Malaysian ringgit on one condition: find a foreign partner.

The answer came in the form of China’s Zhejiang Geely, which made a 49.9 per cent investment. This made Geely the first Chinese carmaker to enter the Southeast Asian market, taking a share of a market in which indigenous carmakers are protected by high tariffs on imports through the National Automotive Policy. Geely may have been foreign, but it was Chinese and Malaysia is 25 per cent Chinese. Malaysia kept face, its people’s car marque, and the jobs of 12,000 employees, while DRB-HICOM divested its loss-making holding.

Mahathir served as chairman of Proton until 2016, and his involvement drew criticism from Najib Razak, whom Mahathir defeated in last month’s election. Zhejian Geely has since struggled to turn Proton around.

So can the great survivor, the comeback king, get it right this time? If Malaysia and its Southeast Asian automotive partners can right the numbers that undid Proton, and create a niche, low-emission car for the driverless age for the domestic and export markets, Mahathir may well confound the sceptics.

Brand China is tarnished in Malaysia and ties between Japan and China are strained. With the precedent of a 15-year history with Mitsubishi, a new Malaysian national car will have a willing suitor. And Mahathir – who as a young doctor once sported a chauffeur-driven Pontiac Catalina – surely dreams of sitting in such a vehicle passing a Proton on the Kuala Lumpur Ring Road.

Above all, this is not just about a car: it is about face, and one man’s enduring obsession with the automobile as legacy.

At 92, Mahathir may cut a late Churchillian figure, but the room is with him. He is too astute not to learn from the lessons of history.

If he and his administration can be seen to redress the mismanagement and corruption endemic under his predecessor – much of it fuelled by the scale of Chinese investment – he may yet be indulged in his latest and probably last automotive dream.

Brand Proton may be dead and the Saga may have run out of road: but there are plenty more Malaysian indigenous trees from which to choose. Anyone for globosus? ■

Jonathan Mantle is the author of ‘Car Wars’ and ‘Companies that Changed the World’