Why so few Asian authors in airport bookstores?

The region needs an international-standard publisher to promote and explain Eastern perspectives to a global audience to complement Asia’s growing power and influence

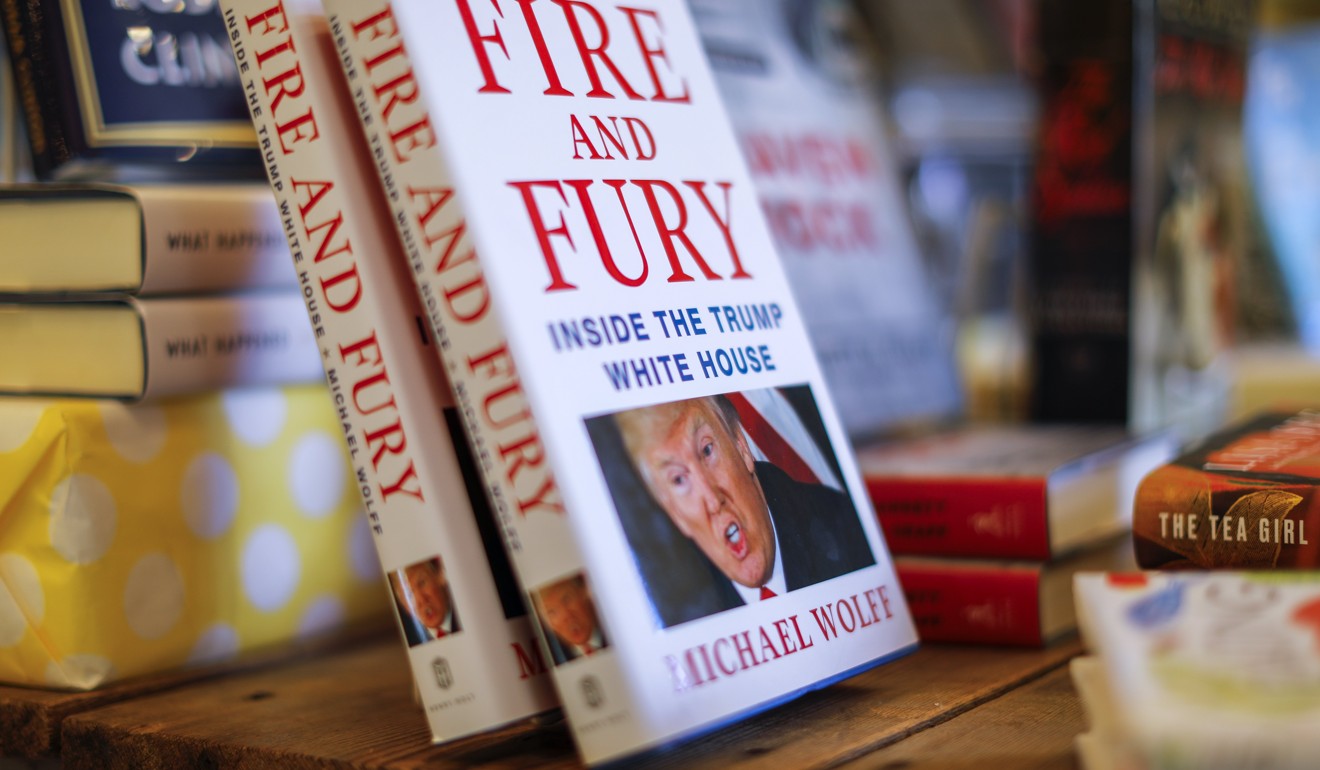

Walk into any international airport’s bookstore and, regardless of where you are, you’ll find the same types of books. There will be the one extolling the virtues of the latest American or European business tycoon. Several will debate the first years of US President Donald Trump’s White House. One will discuss technological disruption as viewed by Western experts. There will be several thick volumes about the first or second world wars, redescribing the victories of the Allies.

When you find a non-Western topic on a bookshelf, the book is invariably written by a Western writer (not to belittle the good writing or research that went into it).

This array of books offers slim pickings for non-Western customers or those interested in more global perspectives. The airport bookstore is the most visible representation of how little the cultural conversation deals with Asia. “Best of” lists from mainstream publications rarely feature books about Asia written by Asians.

The blinkers extend upwards to the highest levels: the Nobel Prize in Literature, for example, has only been awarded to five authors in Asia, and to no Indian author since 1913.

This sadly reflects a world where the wealth of non-Western knowledge and perspectives goes unrecognised and unpublished. This is not just a tragedy, but a practical problem, given the region’s growing prominence in world affairs. Asia, and indeed the world, needs other sources of knowledge to balance what is written in the West. Either Western publishers should recognise this opportunity for new ideas and customers – or Asia must give birth to its own group of publishers.

Asia does not have an international commercial publisher focused on the Asia market as a whole. Such a publisher would not just sell Western books to Asian readers, or sell Asian books to Westerners, but would also sell Asian books to Asian readers to knit together a truly “pan-Asian” reading audience.

China, India and Indonesia have large reading populations; some Western publishers have, in fact, launched imprints in India to publish Indian books for local readers. But, as of now, these industries are local. In contrast, Western publishers sell their work globally, including to many non-native English markets.

One would think that Asia would have enough English speakers to sustain a commercial English-language publisher (as opposed to an academic publisher, such as the National University of Singapore Press or Hong Kong University Press, or the few boutique publishers with limited regional reach). Hong Kong and Singapore are international cities that use English as one of their official languages; Australia and New Zealand are “Western” reading markets whose futures depend as much on their Asian neighbours as their Western counterparts. A couple of large English-language publishers in Asia would also be able to challenge the bias of retailers unwilling to showcase Asian writers. Finally, one could likely find a rapidly growing population of English speakers with at least some level of fluency in every Asian country.

More prominent Asian voices could only be a good thing. The region needs role models as its people develop new businesses, public policies and systems of government. It needs insights based on local research by its own writers, academics, business leaders, researchers and historians. Imagine how illuminating a “rewriting” of the region’s history as seen through the eyes of Asians could be?

Finally, there is a huge number of Asian writers with little chance of getting their work published. Writing is a tough business, regardless of where you live. Even in Western markets, there are countless writers who do not see success.

But we can agree that a good writer based in Ho Chi Minh City or Jakarta with a unique point of view would have a harder time getting published than a writer in Manchester or Sydney.

An international-standard publisher based out of Asia would need to do three things.

First, it must market and sell directly to Asian populations. Second, it would need to search for new and insightful Asian works, in English and other languages, and present them to a global audience.

Finally, it would need to act as the middleman between Asian authors and Asian readers. Asian authors would no longer need to define success as “making it big” in the West (which inevitably leads to a form of literature which panders to Western tastes), as they could succeed with Asian customers.

It would be remiss to ignore past pursuits of the “pan-Asian” market. Several publications, such as Asia Week and The Far Eastern Economic Review, were guided by the vision of an English-speaking market that stretches from Seoul to Sydney, only to be closed or continued in a much-reduced form.

Some have since argued that this means that a “pan-Asian” market of English-speakers does not exist. This may have been true in the past, but things are certainly different today, and changing rapidly.

First, the links connecting Asian countries are far tighter than they used to be. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) integration and China’s rise have encouraged cheaper, faster and tighter connections. The internet and smartphones also make marketing and distributing writing across international borders easier. The population of English speakers is now broader. In 2013, the British Council estimated the number of English speakers would swell to two billion by 2020. An analyst at Australia’s Centre for Independent Studies estimated there were 800 million English speakers in Asia alone.

Finally, Asia is more confident. The West’s missteps in the 21st century mean that Asian ideas and models are treated more seriously as potential models for the region and the rest of the world to follow.

If this works, it would help create a model for how publishing could succeed in the 21st century, especially outside the West. Having a publisher develop a successful model in the “pan-Asian” market – more disparate, diverse, and disconnected – would present great challenges, but determining a path forward for publishing in the digital age will be useful not just in Asia, but in the more mature markets of the US and the UK.

Building a pan-Asian publisher will be challenging. Some have tried before, at a time when the market may not have quite yet been ready. But perhaps the time for a “pan-Asian” market in publishing has come – or, perhaps, will come soon. A publisher based here in Asia will be well-placed to help drive the conversation about Asia’s future, as it tries to understand its own path in the 21st Century. ■

Chandran Nair is founder and CEO of the Global Institute For Tomorrow