Indonesia could be Beijing’s best belt and road friend

- Indonesia needs Chinese investment to close its gaping infrastructure gap so that development can be distributed equally across the archipelago

- But China also needs Indonesia to reach its economic goals overseas, say Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat and Dikanaya Tarahita

China has been one of the biggest foreign investors in Indonesia, spending no less than US$2.37 billion last year to finance 1,562 projects. And with new investments expected from agreements signed at last month’s Belt and Road Forum, China could soon be the archipelago’s largest investor.

This comes as no surprise, given the increasing convergence of interests between both economies.

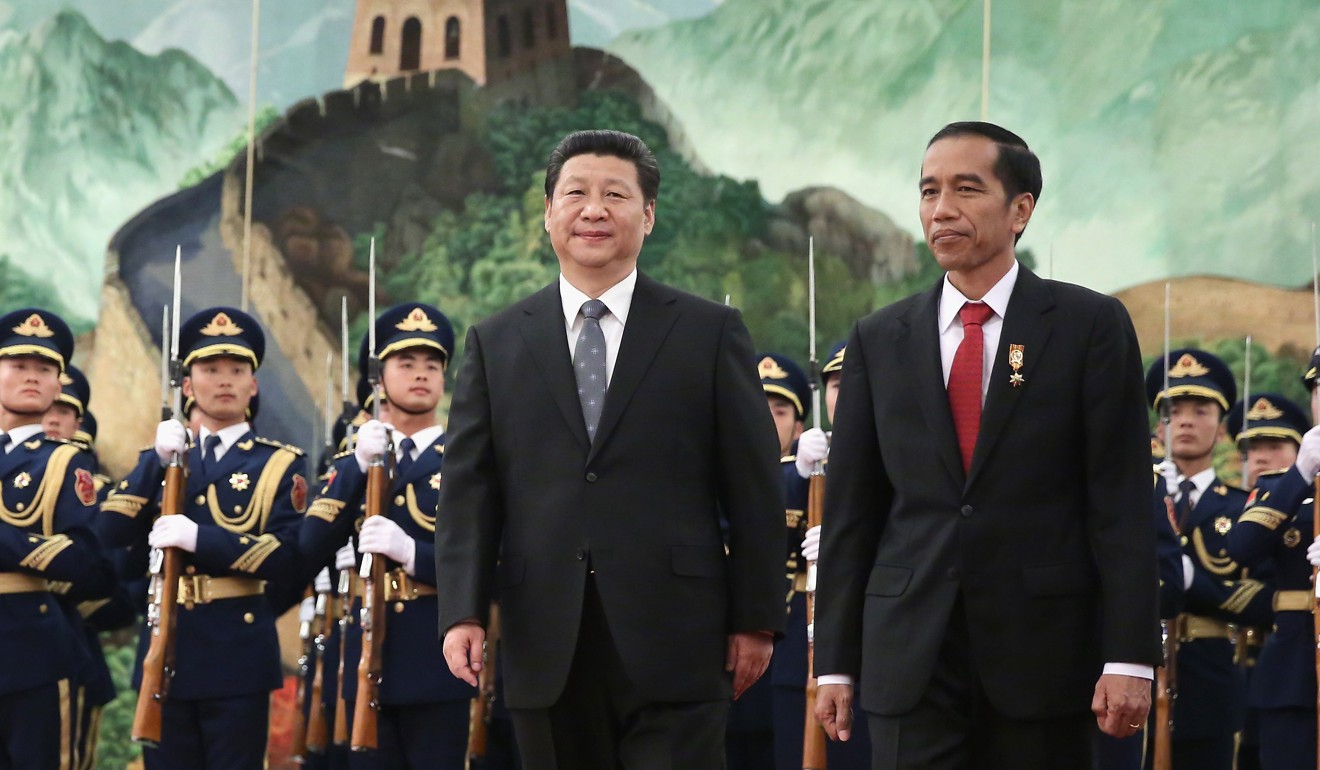

Incumbent president Joko Widodo, popularly known as Jokowi, has shown his commitment to further develop the country’s infrastructure and attain growth of 7.3 per cent.

Jokowi has prioritised the development of eastern Indonesia, which currently has poor infrastructure. But the country’s US$353 billion budget for the 2019-2020 financial year is far from enough to bridge the infrastructure gap so that development is distributed equally across the archipelago of 17,000 islands.

This is where China can play a role. One of China’s approaches to foreign policy has been to offer loans and investments to developing countries seeking to improve their crumbling infrastructure. This is a way for China to solve its overaccumulation of manufacturing capital in areas such as steel and asphalt, which need profitable outlets. The Belt and Road Initiative is expected to help channel this excess abroad.

But China’s interest in Indonesia goes beyond Jokowi’s infrastructure policy intersecting with its belt and road objectives.

The West has taken a tougher stance on China by reinforcing barriers to entry for Chinese businesses. Last year, Chinese investments in the United States and Canada were all but wiped out, nosediving 92 per cent from the previous year to US$2 billion, likely a result of the US-China trade war and a diplomatic spat over Huawei. Bilateral ties between Canada and China turned cold in December when Vancouver police arrested Huawei’s chief financial officer Sabrina Meng Wanzhou on a US warrant. Since then, China has arrested two Canadians and halted canola imports from two Canadian companies, with pork imports from two producers also banned.

The same is happening in Australia, with Chinese investment going down to US$8.2 billion last year compared to US$13 billion in 2017. Mining led the downside with a 90 per cent slump in investment to US$464 million.

Analysts have pointed to the changing nature of investment flows, with KPMG Australia’s head of Asian and international markets, Doug Ferguson, saying: “Chinese investment is definitely now flowing globally to Central Asia and Eastern Europe in accordance with the belt and road initiative.”

In diverting funds from the West, China has expended more effort to gain market share in other countries, especially those in regions that the belt and road plan covers.

Being the largest economy in Southeast Asia with a strategic location, Indonesia has become a priority in Chinese President Xi Jinping’s ambitious effort to revive the traditional Silk Road.

So while Indonesia may need Chinese investments to improve its economy, China needs Indonesia to reach its economic goals overseas.

And Indonesia is a good place to do business. Research by global consulting firm PwC, published in February last year, predicts it will become the fourth-largest economy in the world by 2050, behind China, India and the US.

The country’s middle class is growing and is expected to eventually make up 22 per cent of the population – from 45 million in 2010 to 60 million this year and an estimated 85 million by 2020.

Consumers are more affluent and the large pool of millennials – more than half of the country’s population of 265 million is estimated to be under the age of 40 – makes Indonesia an attractive target market for Chinese companies selling consumer goods and services.

Consumption is surging too, with consumer spending in the first quarter of 2019 reaching an all-time high of 1.44 quadrillion rupiah (US$98 billion). Looking forward, the number is projected to trend towards US$116 billion by 2020.

China has already recognised this – it supplied Indonesia with US$45.24 billion worth of goods last year, making up more than one-quarter of the country’s total imports.

Looking at these factors, it is not surprising that China sees Indonesia as an attractive country in which to implement its belt and road plans. Even in the midst of domestic opposition to “foreign domination”, it is likely to continue trying to realise its interests in the country. It knows all too well that the its planned belt and road maritime route from China to Europe is not possible without Jakarta.

Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat is a lecturer at the Islamic University of Indonesia and research associate at the Institute for Development of Economics and Finance in Jakarta

Dikanaya Tarahita is a human resource researcher and independent journalist based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia