Sant Kabir and spiritual rationalism in Narendra Modi’s India

- While Hindu nationalism and the primordial power of caste may seem all-pervasive in modern India, the questioning and challenging of both goes back hundreds of years

When Sant Kabir, the 15th-century mystic and poet, walked out of the city now known as Varanasi, in northern India’s Uttar Pradesh, he must have known he was leaving for the last time.

Devout Hindus, in the twilight of their lives, have long sought to head towards Varanasi and spend their remaining days in their religion’s holiest of cities alongside its holiest of rivers, the Ganges.

In contrast, Kabir chose to walk away, despite the wizened iconoclast having been born there – rejecting ancient Hindu practice and orthodoxy.

He was not the first and will not be the last to take the road away from Varanasi, forsaking the world of Brahmins and casteism. Indeed, while Hinduism – or rather, its Hindutva nationalist strain – and the primordial power of caste seem all-pervasive today, the questioning and challenging of both goes back to the time of the Gautama Buddha, who died nearly a thousand years before Kabir was born.

In fact, Kabir would most probably have passed the ruined monasteries and temples at Sarnath just outside Varanasi where the Buddha delivered his first sermon. While Buddhism itself has waned in its Indian birthplace, the reformist trends it started continue well into the present.

And Kabir was very much a champion of the reformist bhakti tradition. Born into a lowly weaver caste, he nevertheless studied Hindu scriptures and it is this eclecticism and passionate embrace of humanity that enriches his poetry. It possesses a stark beauty – celebrating both spirituality and pluralism – whilst dismissing hypocrisy and cant.

Kabir – at least in his afterlife – has since been claimed by both Hindus and Muslims. Indeed, there’s a legend that when Kabir died, locals from both faiths fought for the right to bury his remains according to their customs – but as they lifted the shroud that was covering his body, all they found were wildflowers. These were then divided: the Muslims buried their portion in Maghar while the Hindus brought theirs back to Varanasi to be cremated.

When Team Ceritalah visited the tomb in Maghar, in Uttar Pradesh’s Sant Kabir Nagar district, we came across a place of great reverence for both Hindus and Muslims. Even the Dalits (formerly so-called untouchables) flock here to pray for good harvests, jobs for their sons and protection from landlords.

Understandably perhaps, Kabir’s legacy has remained hotly contested and in an “only-in-India” moment, the BJP-backed prime minister, Narendra Modi, paid a visit to the tomb in June to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the sant’s death.

It seems as if Kabir, who in his life espoused a spiritual rationalism totally at-odds with (and arguably dangerous in) Modi’s India, is now being appropriated by all.

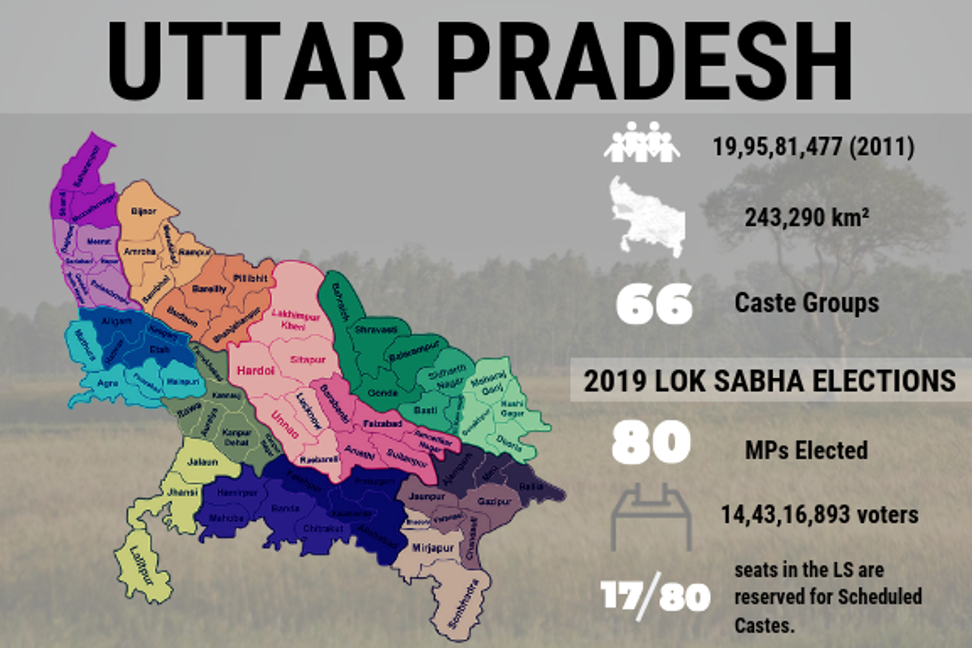

Moreover, when it comes to politics and society in India, all roads seem to lead to the Ganges. This is probably unsurprising when one considers, as Ceritalah has highlighted time again, the importance of Uttar Pradesh.

Of course, there’s more to India than just this one state, albeit the most-populous one with the most MPs. But Uttar Pradesh – including its portion of the Ganges – has been the birthplace of not just religious, but radical political movements.

Five centuries after Kabir, the socialist Ram Manohar Lohia rallied rural peasants, Ganges boatman and the sant’s weaver caste in opposition to the state’s feudal landlords.

Fast-forward to today and we find two Uttar Pradesh-based parties, the Samajwadi (SP, led by Akhilesh Yadav, a former chief minister of the state) and the Bahujan Samaj (BSP, led by another former chief minister, Mayawati) emerging as arguably the only real opposition to the BJP in the state.

While his father Mulayam Singh remains influential, Akhilesh’s SP sees itself as a continuation of Lohia’s socialist struggle, now backed by the agrarian Yadav caste. The impact of this was best seen in the small eastern Uttar Pradesh town of Basti, where Team Ceritalah found its local college brimming with students thanks to government scholarships and wizened old grandmothers receiving a monthly widow’s pension.

Mayawati’s rise to become a Dalit icon on the other hand has been well-documented. She also controversially sought to rename places or build monuments for the Dalit pantheon, such as B.R. Ambedkar.

This naturally runs counter to the vision of the BJP, which leads the state via the militant Hindu monk Yogi Adityanath. It speaks volumes that Adityanath – who has courted notoriety with his anti-Christian, Islamophobic and sexist tirades – is perceived as having turned his back on Uttar Pradesh’s capital, Lucknow.

Once the epicentre of the prosperous Awadh Muslim kingdom, the city of steep mosques and decadently rich biriani is everything that the Yogi and his BJP colleagues do not want India to be. It’s syncretic, a melting pot of cultural enrichment and courtly yet still endowed with a sense of fun.

Both Hindu and Muslim residents of Lucknow feel ignored if not disdained by the government that is housed in their own city, an occurrence they would never have thought possible.

Adityanath returns almost every night to his hometown of Gorakhpur, 270 kilometres away.

Perhaps inevitably, the latter is known for its Gorakhnath Math temple. When not busy being chief minister, Adityanath runs a large ashram and an armed religious outfit called the Hindu Yuva Vahini there.

Another “only in India” fact: Gorakphur is really close to Maghar, where Kabir reposes in a Muslim shrine.

Locals we talked to joke that their little town has become Uttar Pradesh’s second capital. Indeed, hamlets like theirs are where Adityanath has his base, eschewing the BJP’s former embrace of cities like Lucknow.

Under Adityanath, the party is showing that they too can play at “renaming” politics, with Allahabad now officially known as “Prayagraj”, while also pouring support into the Kumbh Mela festival that occurs every six years at the meeting of the Ganges and the Yamuna in Varanasi.

When Team Ceritalah gazed upon the Ganges, its gentle brown waters were flowing placidly. But this calm might be as deceptive as voting in the country’s drawn-out elections that ended on Sunday.

Kabir may have walked away from Varanasi. But his remains – if you believe the legend – partly rest there, cremated in Varanasi and buried in Maghar, both near or on the Ganges.

The Ganges has been the source of livelihood for the people who dwell on its banks. It has also birthed and sustained not only faiths that have captured the consciences of millions all over the world, but also the many facets of India’s identity: pluralistic and fanatic, radical and reactionary, egalitarian and caste-ridden.

Which will prevail in the end? We’ll find out soon enough, but whatever happens: the Ganges will continue to flow.