China, Japan and South Korea must choose: history or economics

- The three countries have a complicated rivalry over war history and territorial claims, but economic cooperation remains their biggest bond

- Leaders recently shared their desire for a free-trade agreement in a market of over 1.5 billion people

The historic tales of China’s ancient Three Kingdoms can be used to explain the complicated rivalry between China, Japan and South Korea, which have often had troubled relations despite their geographical proximity, similar cultures and close economic ties.

The three East Asian powers have taken turns at being the envy of the world with their miraculous growth after World War II, first seen by Japan, then South Korea and China. Today, China is Asia’s largest economy, Japan second and South Korea fourth. Combined, they account for a quarter of global economic output.

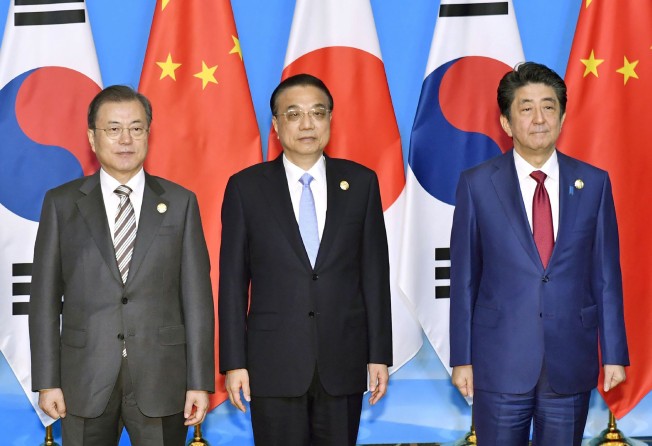

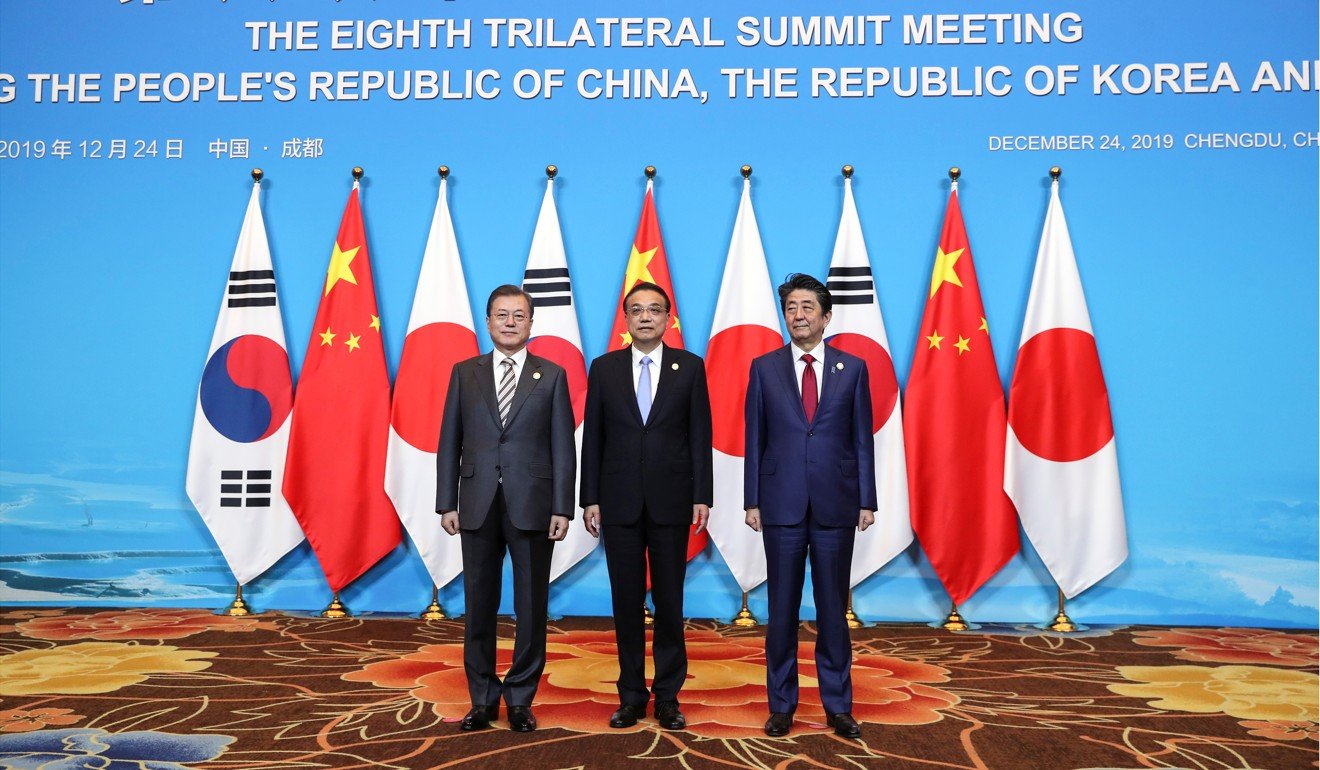

That is why the leaders of these nations, who met in a trilateral summit in China’s south-western Sichuan province on December 24, shared their desire for peace and prosperity despite the increased tensions on all sides of the regional triangle over the past decade.

Since the first summit in 2008, bilateral relations between Beijing and Tokyo, Beijing and Seoul, and Tokyo and Seoul have been locked in bitter disputes over war history, territory, regional security and other issues.

The modern history of East Asia saw Japan colonising China and Korea, followed by the 1950-53 Korean war that divided Korea into two opposite alliances, in which communist China fought on the side of North Korea and Japan on the side of South Korea, led by the United States.

Relations have become more complicated following dramatic geopolitical changes in the last few decades, which saw China become the world’s fastest-rising major power; Japan the world’s fastest-declining one; and South Korea an emerging regional economic and diplomatic power.

The Sichuan summit celebrated more than 20 years of cooperation, originally dating back to the aftermath of the 1997 Asian financial crisis. However, trilateral initiatives seeking to build confidence and trust have been slow to get going, not just because of the historical feuds but also because of divergent or conflicting geopolitical interests.

The summit came amid a bitter quarrel between Tokyo and Seoul, the uncertainty caused by the escalating trade war between the US and China, as well as the threat of North Korea resuming nuclear tests.

Sino-Japanese relationsrecovered only after Shinzo Abe’s ice-breaking trip to Beijing in October 2018. This was the first visit by a Japanese prime minister since 2011, when relations took a nosedive following a 2012 territorial dispute over a string of islands in the East China Sea, called the Senkakus by Japan and the Diaoyu by China. Anti-Japanese sentiments still run high in China as a result of the government’s high-profile World War II memorial activities in recent years.

Sino-Korean relations also experienced a major setback following Seoul’s agreement to deploy the US-built Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD) missile system in 2016 which Beijing viewed as a threat to its security. This led to an unofficial boycott of South Korean goods and movies, as well as a steep decline in the number of tourists.

Ties between Tokyo and Seoul have hit rock bottom in recent months over trade and a bitter feud related to Japan’s 1910-1945 occupation of the Korean peninsula. In late November, Seoul narrowly opted to continue an intelligence-sharing pact with Tokyo, reversing its prior decision to withdraw from the accord after intervention from Washington.

Economic cooperation remains the most significant bond between the three trade powers. Leaders shared their desire for a free-trade agreement in a market of over 1.5 billion people with trilateral trade of US$720 billion last year, which accounted for just shy of 24 per cent of the global total.

China is Japan’s largest trading partner and Japan is China’s third-largest export market. South Korea is also an important trade partner for both China and Japan.

Beijing sees the trade pact as an important part of its efforts to increase regional economic integration and diversify its markets in the face of escalating trade tensions with the United States. The three-way trade accord would lead to a tariff reduction on around 92 per cent of tradeable goods, making it one of the biggest multilateral free-trade deals China has negotiated.

The accord could also pave the way for Beijing and Seoul to join Tokyo in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a free-trade agreement which involves 11 Asia-Pacific countries, excluding the US. China was excluded from the pact when it was first drafted in 2015 under then US President Barack Obama’s “pivot to Asia” policy to counter Chinese influence. However, US President Donald Trump withdrew the US from the pact when he came to office.

Leaders also agreed to jointly push for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), an expansive multilateral trade deal spanning the Asia-Pacific, although its future is uncertain following India’s recent abrupt withdrawal.

Shared concerns over the threat from North Korea’s nuclear ambitions have long glued the three countries together diplomatically. The failures of three meetings between Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un prompted Tokyo and Seoul to seek Beijing’s help to break the impasse, as China is seen as North Korea’s sole ally and supporter.

Pragmatism might prevail as leaders hope booming business relations would help heal the festering wounds.

Beijing is also trying to exploit its two Asian neighbours’ increasing frictions with the US. The Trump administration threatened to punish Tokyo and Seoul over its complaints about the cost of maintaining US troops there. They are also at odds over trade issues.

However, Beijing’s shift from its “low-key” diplomacy to a high-profile and increasingly assertive posture in recent years has triggered distrust and animosity in the hearts of its Asian neighbours. The Pew Research Centre’s Global Attitudes survey in September suggested a record 85 per cent of Japanese and 63 per cent of South Koreans view China unfavourably, despite the improving ties.

Viewing China’s fast-rising military clout as a major threat to their security, Tokyo and Seoul have moved to forge closer defence ties with Washington, joining in a tripartite security system that would play a critical role in deterring China, along with North Korea and Russia.

Indeed, pragmatism might prevail as leaders hope booming business relations will help heal the festering wounds as a result of disputes over wars, history and territory, and strategic distrust. Ties will be repaired in anticipation of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s first state visit to Japan and expected trip to South Korea early this year.

But Tokyo and Seoul, as like-minded US allies, will side with Washington in the event of any military confrontation between the world’s two biggest rivals and political adversaries.

There is no historical period that offers richer theoretical arguments and insight into diplomacy and geopolitical strategy than the legendary Three Kingdoms era between AD220 and 280. One lesson from that time is that weaker states often ally themselves in an effort to resist the strongest, as seen by the alliance between Shu, based in Sichuan where the trilateral summit was held, and Wu in East China, against the Northern power of Wei.

The era was also full of tricks and conspiracies in battles, either at the negotiating table or on the field, as rivals lacked confidence and trust in each other. ■

Cary Huang is a veteran China affairs columnist, having written on the topic since the early 1990s

Purchase the China AI Report 2020 brought to you by SCMP Research and enjoy a 20% discount (original price US$400). This 60-page all new intelligence report gives you first-hand insights and analysis into the latest industry developments and intelligence about China AI. Get exclusive access to our webinars for continuous learning, and interact with China AI executives in live Q&A. Offer valid until 31 March 2020.