After Sri Lanka’s parliamentary polls, the Rajapaksas have their job cut out

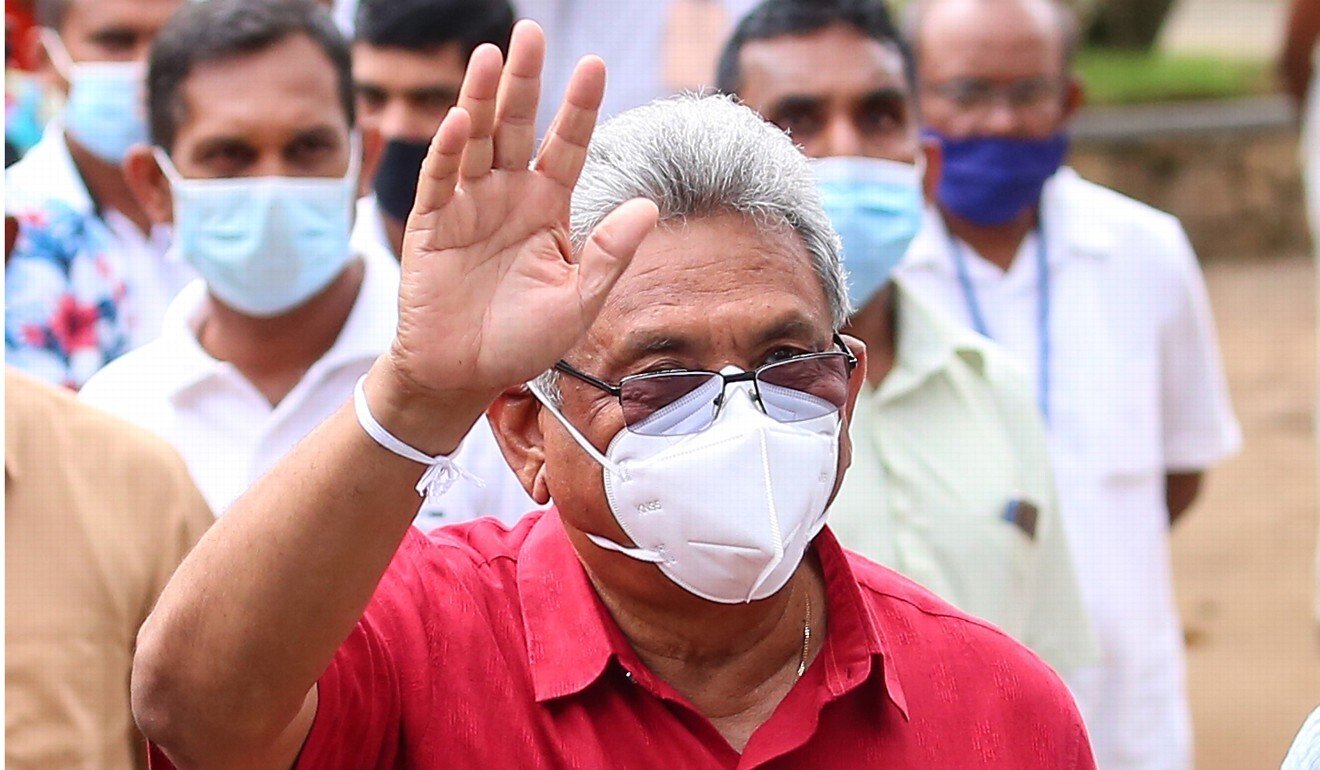

- The SLPP of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa and Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa won a two-thirds majority to effect constitutional reforms

- The West will have to rethink its Sri Lanka strategy, while the country will have to choose the straight and narrow path with China and other countries

Wednesday’s parliamentary polls have reaffirmed Sri Lanka’s faith in the ruling Rajapaksa government. However, the electoral decimation of the United National Party (UNP), the nation’s “grand old party”, and the weakening of the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), have a message, especially for the West, which now has to rethink its Sri Lanka strategy.

With the support of two Tamil allies who strategically contested alone, the Rajapaksa-led ruling Sri Lanka Podujana Party (SLPP) now has a total of 151 MPs, including Speaker, in the 225-member Parliament, giving it a two-thirds majority to effect promised constitutional reforms aimed at restoring executive power that was haphazardly diluted by the previous government, in office from 2015-19.

Despite two postponements caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, the effective management and containment of the virus – Sri Lanka has had 11 deaths and 2,900 confirmed cases – helped the Rajapaksa imagery in the parliamentary polls even more.

However, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s induction of uniformed officials, both serving and veterans, to lead task forces to address administrative hiccups has run into criticism for more reasons than one. In an ethnically-charged nation, Tamil-Hindus and Tamil-speaking Muslims see an entirely Sinhala-Buddhist task force to manage archaeological sites in multi-ethnic Eastern Province as an attempt to usurp their ancient history and places of worship.

Communication hiccup

The poll results may make diplomatic communication with Sri Lanka difficult as there is mutual distrust and discomfort between the West and ruling Rajapaksas.

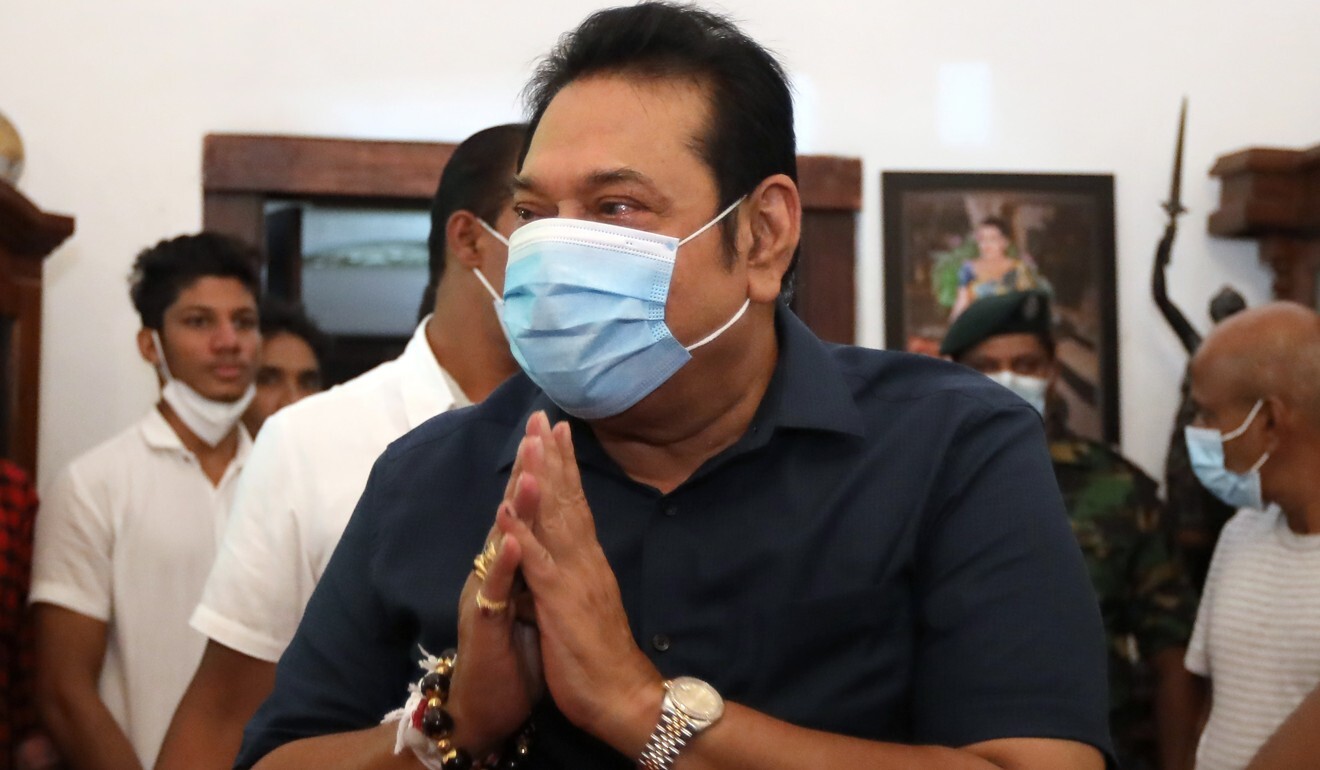

After the defeat of the UNP and dishonourable exit of three-time prime minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, the Rajapaksas have an opposition leader with an equally strong rural bias in Sajth Premadasa, leader of the breakaway SJB and son of former president Ranasinghe Premadasa, who was slain by the Tamil Tigers. The SJB is targeting their Sinhala-Buddhist nationalist constituency.

Having assumed moral responsibility to ensure justice for the war-affected Tamil minorities, the Rajapaksas will find communicating with the new hardline Tamil nationalist MPs tougher. The moderate TNA, seen as the West’s trusted ally, has fewer MPs now, forcing them to also take a tougher stand on the ethnic issue, when Western powers seemingly want to acknowledge the ground realities and rework their equations with the Rajapaksas.

Economy & foreign policy

The election results have legitimised Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa’s term, which commenced with his nomination by his brother Gotabaya on assuming office following a comfortable election victory last November. Their return to power after a five-year hiatus has restored a sense of political stability and national security, absent during the West-sponsored disastrous cohabitation of former president Maithripala Sirisena and prime minister Wickremesinghe.

For the next four years, the Rajapaksas have their job cut out. Truth be told, constitutional reforms can wait, given that the cohabitation this time is between brothers, and the accompanying ethnic issue cannot be resolved overnight. But the tottering economy cannot wait. Acknowledging this, the no-nonsense Gotabaya used his maiden overseas visit late last year to frankly ask neighbouring India for a US$1.5-billion cash swap facility and a three-year moratorium on a US$900 million loan.

New Delhi has since signed in the first instalment of a US$400 million cash swap and “technical discussions” are continuing.

India has its own concerns over Sri Lanka in matters relating to China, more so after the recent border stand-off and violence, followed by the “cartographic mischief” on a new national map that Nepal and Pakistan separately produced, purportedly at Beijing’s instance.

New Delhi did not have a problem when the earlier Rajapaksa government offered the Hambantota port construction-cum-concession contract to China. It was different when Colombo offered a berth for China’s submarines, and when the next Sri Lankan government handed over the Hambantota port to China on a 99-year lease. After stating before the election that he would review the new Hambantota deal, once elected, Gotabaya declared it was a “commercial agreement” and he could do nothing about it.

Trilateral agreements

India’s China concerns are security-centred, as are those of Sri Lanka’s other friends like Australia, Japan and the US. Forming the Indo-Pacific Quad, these four allies are worried about China’s expansionist tendencies in the Indian Ocean, and also the South China Sea and East China Sea. Sri Lanka cannot have it both ways, and the days of Colombo using locational advantage to bargain with bigger powers have to end.

India and Japan signed trilateral agreements to develop the historic eastern Trincomalee port and city, and to build Colombo Port’s Eastern Container Terminal (ECT). But the Rajapaksas have stalled India’s participation in the ECT project, confirmed by the previous administration, citing protests by left-leaning labour unions and self-styled Sinhala-Buddhist nationalist supremacists.

On the US front, the current government is “reviewing” its predecessor’s commitment to US$400 million development projects with concessions similar to some enjoyed by China.

The US is equally keen on the Rajapaksas taking forward the SOFA (Status of Forces Agreement), initialled by the predecessor, with powers for American soldiers to carry their personal arms on Sri Lankan soil and be exempt from local laws. As Sinhala/Sri Lankan nationalists, the Rajapaksas find it hard to accept this and market it to their domestic constituency.

In all this, the Rajapaksas will need reassurance that such cooperation will help blunt the West’s continued antagonism, especially on the war crimes probe against the nation’s armed forces, over which a crucial UN Human Rights Council vote is due in March. It is still a two-way street.

On China and other countries, the Rajapaksas will have to choose the straight and narrow path, without shifting the goalposts often, as was seen during Mahinda’s earlier period in office, if they expect reciprocity from the West and the rest.

N. Sathiya Moorthy is Distinguished Fellow and head of the Chennai Initiative at the Observer Research Foundation, a multidisciplinary Indian public-policy think-tank, headquartered in New Delhi.