How Vietnam has borrowed from China’s online censorship playbook

- Vietnam is keeping close tabs on public online discourse as it seeks to tap into social media-fuelled nationalism

- But it also tolerated online backlash against Jackie Chan over the South China Sea and anger over Singapore PM Lee Hsien Loong’s Khmer Rouge comments

Last week, a restaurant in Quebec, Canada, ate humble pie and promised to make changes to “vulgar and degrading puns” in its name and menu that many Vietnamese considered offensive to their culture.

In November last year, an online backlash declared Hong Kong-born film star Jackie Chan persona non grata in Vietnam. The rationale? Chan was accused of having spoken in support of China’s controversial nine-dash line, a demarcation that includes large swathes of the South China Sea. Vietnam has vehemently objected to such claims.

Only a month earlier, Vietnamese netizens spotted that Abominable , a film co-produced by DreamWorks and the Shanghai-based Pearl Studio, had a map that showed the nine-dash line, and quickly shared screenshots on social media. The film was pulled out of Vietnamese cinemas. This also led to the subsequent demotion of a senior Vietnamese official who was held accountable for allowing the release under her watch.

In June 2019, Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s tribute to the late Thai premier General Prem Tinsulanonda contained the words “invasion” and “occupation” to refer to Vietnam’s actions to oust the Khmer Rouge in the late 1970s, language that Vietnam and Cambodia said was tantamount to support for the genocidal regime of Pol Pot. This sparked a diplomatic crisis not seen in years between Singapore and its two Southeast Asian neighbours.

A wave of social media-fuelled nationalism has turned increasingly potent in the online sphere, leading the Vietnamese authorities to become acutely sensitive to and even accommodating of it. As it has turned out, such successive waves of online nationalism have galvanised all parties concerned – including the authorities – into taking action and making amends. This level of responsiveness is quite remarkable for Vietnam, a country that is believed to have followed in the Chinese footsteps to control the internet.

Granted, governments of all types – freer and those less free – have sought to tap into nationalism to boost their legitimacy. But responsiveness and legitimacy are particularly crucial to the resilience of authoritarian regimes, especially one on the verge of a leadership transition like Vietnam.

In a country where around two thirds of a population of 97 million are online and where Facebook boasts around 47 million active accounts to advertisers, the Vietnamese authorities have become increasingly fixated on gauging public sentiment online.

In November 2018, Vietnam set up a web-monitoring unit capable of scanning up to 100 million news items per day for “false information”. In 2016, the country also deployed a 10,000-strong cyber unit called Force 47 tasked with maintaining a “healthy” internet environment.

It is in this context that Vietnam has sought to appeal to online nationalism. Its propaganda tsars have bemoaned that the mainstream media all too often trail behind Facebook in shaping the narrative and even public opinion. But there were times when the authorities may have felt more comfortable letting the public sentiment online run its course.

Even though Jackie Chan has not been documented explicitly supporting China’s controversial maritime claims, he eventually capitulated, scrapping the Vietnam visit soon after the social media frenzy sent thousands of Vietnamese netizens storming the Facebook page of the host charity, Operation Smile.

In Chan’s case, the authorities remained almost reticent, issuing instead an oft-repeated standard statement that dismissed China’s nine-dash line and asserted Vietnam’s maritime sovereignty.

But notably, on November 6, just two days before Chan cancelled his charity visit, Vietnam’s deputy foreign minister Le Hoai Trung said at a conference in Hanoi that the country did not rule out legal action against China. The statement was made against the backdrop of a simmering stand-off after a Chinese oil survey vessel had been in Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone in the South China Sea since July.

In other cases, the Vietnamese authorities were less reticent, having taken serious note of such public sentiment on social media.

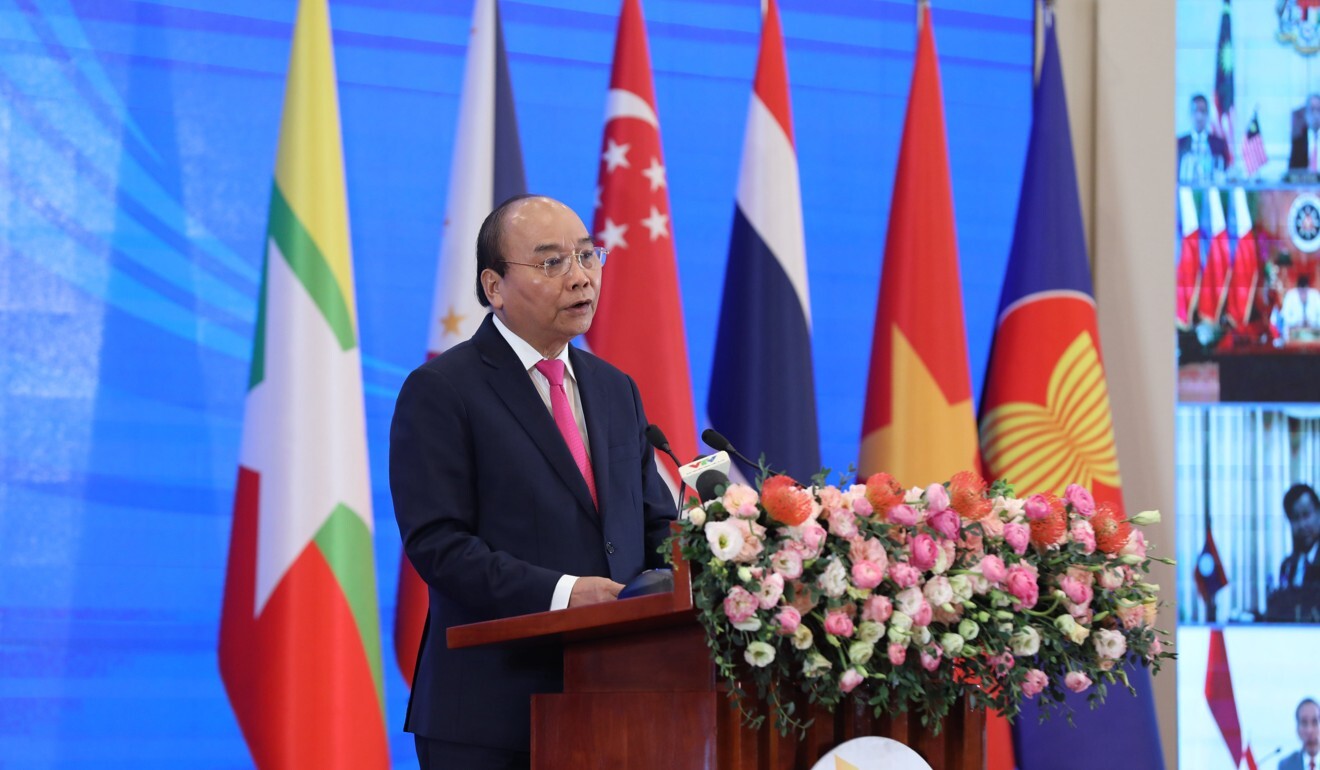

In the wake of the public outcry against the Singaporean prime minister’s words about the Khmer Rouge, Vietnam lodged a diplomatic protest against the city state. At a meeting on the sidelines of a June 2019 regional summit in Bangkok, Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc once again chided his Singaporean counterpart for offending Vietnam and Cambodia.

In January 2018, Daniel Hauer, an American teacher and internet sensation in Vietnam, got into hot water for making offensive comments about General Vo Nguyen Giap, one of the country’s most revered heroes who played an instrumental role in ousting French and American troops from the country. After Vietnamese netizens fulminated against Hauer and demanded his deportation, the authorities summoned him and let the mainstream media publish his public mea culpa.

The fact that Hauer’s subsequent remark in a private Facebook group, in which he disparaged “crazy nationalist” critics, came to light raised several intriguing questions: Was it because the prying eyes of the internet police were everywhere? Or was it simply because an angry netizen spilled the beans on him?

Social media can serve as a pressure release valve for public opinion.

What is apparent is how the Vietnamese authorities have increasingly kept close tabs on public online discourses and tried to be as responsive as they could. As argued elsewhere, social media is a concern for Chinese authorities, not so much for the public criticism, but more so for its ability to fuel collective action or organise protests. This is perhaps one of the most important chapters that Vietnam, a country that prizes political stability above all else, has taken from China’s online censorship playbook.

The takeaway here: As long as collective action is prevented, social media can serve as a pressure release valve for public opinion or even leave some elbow room for online activism.

Vietnam has been successful in tapping into nationalism to coalesce the public around the fight against the Covid-19 pandemic, which it has labelled as a foreign enemy. It remains to be seen how the country is going to play the online nationalism card in the lead up to its leadership reshuffle early next year.

Dien Nguyen An Luong is a Visiting Fellow with the Media, Technology and Society Programme of the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. This piece was first published in ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute’s ISEAS Commentary – 2020/135 on September 11, 2020.