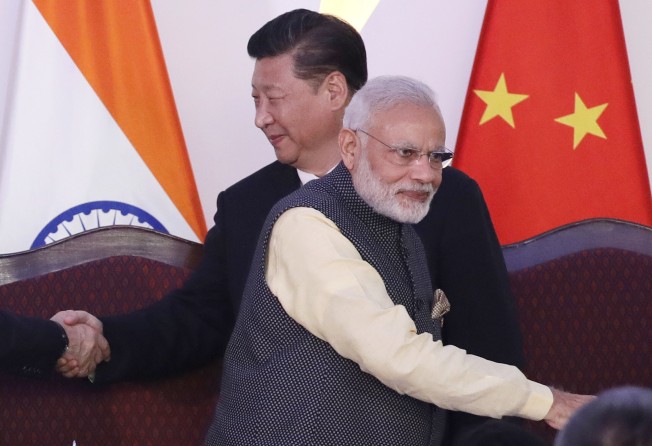

A year after deadly Galwan Valley clashes, India and China are struggling to rebuild mutual trust

- India has been willing to defer to Beijing’s ‘sensitivities’ on certain critical issues but is now seeking to redraw these red lines, insisting on reciprocity

- Despite both sides talking of peace, the ‘fog of war’ lingers, with competing narratives reinforcing perceptions of enduring rivalries

Under India’s presidency at the UN Security Council, there was this month an unprecedented stand-alone session devoted to maritime security, reaffirming the international rules-based order at sea.

Previously, such discussions have been prevented by Beijing’s sensitivities regarding the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and the overlapping territorial claims in the South China Sea.

Despite Beijing sending only a deputy permanent representative, India welcomed global support, including Russian President Vladimir Putin’s presence. From New Delhi’s perspective, the discussions were worthwhile.

Other actions – the recent naval exercise with Vietnam in the South China Sea, upcoming Malabar exercises with Quad partners near Guam and the recently concluded Colombo Security Conclave – underline India’s intent to expand partnerships and interoperability in the Indo-Pacific.

In the past, India has been willing to defer to Beijing’s sensitivities on certain critical issues. However, one year after the deadly clashes in the Galwan Valley, India is determined to redraw these red lines.

New Delhi now demands Beijing respect its concerns in areas it regards as equally important, insisting upon mutual respect as a prerequisite for rebuilding trust in a relationship that has become deeply strained. This is the new normal in India-China relations.

The two countries have held talks designed to de-escalate tensions along the countries’ shared border, known as the Line of Actual Control (LAC). Both sides have sought to continue dialogue but also seem willing to agree to disagree.

The official statements after India’s Foreign Minister Dr S. Jaishankar met his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi in July reflected this trend.

New Delhi maintains that issues of de-escalation at the LAC and cooperation with Beijing in other areas are linked. China, on the other hand, insists these issues be treated separately.

India’s statement reiterated “unilateral change along LAC was unacceptable” and “emphasised the need to follow through” on China’s previous commitments.

China’s statement said “the two sides must place the border issue in an appropriate position in bilateral relations” and “expand the positive momentum of bilateral cooperation”.

Vijay Gokhale, India’s former foreign secretary and ambassador to China, in July told The Hindu newspaper that Beijing’s “insensitivity” and its insistence that other countries consider issues according to Beijing’s perspective, was a weakness of Chinese diplomacy that other countries would begin to exploit.

The narratives being promoted publicly around Tibet are a case in point, and there are implications for the border dispute as China claims the entire Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh as “Southern Tibet”.

Beijing protested when US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken last month met representatives of the Dalai Lama and the exiled Tibetan government while visiting New Delhi. Chinese nationalist tabloid Global Times published a story about Beijing’s embassy in India opposing the meeting, as well as a cartoon suggesting the US was encouraging confrontation between China and India.

India sent a clear message when Prime Minister Narendra Modi wished the Dalai Lama a happy birthday last month. As villagers in eastern Ladakh celebrated the date, they also complained of Chinese army personnel across the Indus River near the LAC raising banners in protest.

Equally, events in China have caught New Delhi’s attention. Chinese President Xi promoted four senior military officers, including one who was at the centre of the Ladakh border conflict, to generals.

Before its independence day, India also presented bravery medals to 20 members of Indo-Tibetan Border Police who fought alongside the Indian Army in the Galwan Valley. Last year, a public funeral was organised by security forces for Nyima Tenzin, a soldier of Tibetan origin who was deployed with India’s elite Special Frontier Force during the clashes.

Despite both sides talking of peace, the “fog of war” lingers. Indian media reported 40 PLA soldiers were spotted on July 21 patrolling the central sector along the LAC near Barahoti.

Indian government agencies are also reportedly monitoring the PLA Air Force’s new base in Shakche near Ladakh, which supports China’s rapid response for combat operations. Indian government sources have been quoted saying China proceeded with the development of the Shakche base after assessing that the Indian Air Force was able to move into the conflict zone more quickly than the PLA Air Force.

Chinese state media covered Xi’s visit to Tibet – to Lhasa and Nyingchi, which border Arunachal Pradesh. Xi inspected Tibet’s first bullet train line, linking Lhasa and Nyingchi.

Indian media paid particular attention to comments from Zhu Weiqun, a senior Communist Party official formerly in charge of Tibet policy.

“If a scenario of a crisis happens at the border … the railway can act as a fast track for the delivery of strategic materials,” he said, Chinese state media reported.

India views China’s attempts to keep multiple points alive along the LAC as coercion. It is particularly sensitive to Chinese state media’s coverage of “Arunachal’s slow pace of development”.

According to Manjeet Pardesi, a professor of political science and international relations at Victoria University of Wellington, the lack of mutual trust stems from the fact “China perceives India as an asymmetric ‘imperial’ rival that interferes in China’s Tibet”, creating reputational cost for China.

This causes China to “lose face” when “it desires to be seen not just as a powerful country but a distinctive civilisation”, Pardesi said.

India has pointed out that respect for these “sensitivities” is a two-way street. It too regards China’s actions – including its obstruction of India’s infrastructure build-up and provocation along its borders and in its maritime sphere – as imposing “reputational cost”.

Yun Sun from the Stimson Centre in Washington highlights the Chinese dilemma, as Beijing wants to convey to New Delhi that “an alignment with the US will carry a certain cost”.

However, New Delhi objects to Beijing considering the Sino-Indian relationship through the prism of its rivalry with the US. It also rejects China labelling India’s aspirations expansionist. This conflicts with India’s vision for a multipolar Asia and a multipolar global order.

Both countries have made strategic plays around the other’s sensitivities, and perceptions of enduring rivalries have been reinforced. A year after the clashes in the Galwan Valley, it means India and China are in uncharted territory and the road to recovery is unclear. Competing narratives and absence of a real dialogue have done little to rebuild mutual trust.

Shruti Pandalai works on India’s foreign and security policy at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, a think tank funded by India’s Ministry of Defence. Views expressed here do not reflect those of her employer.