This is no K-drama: the fresh prince of South Korea is real royalty, and he’s American

- Five years ago, Andrew Lee found out his relative Yi Seok, ‘The Singing Prince’, was the last emperor of Korea’s Joseon dynasty

- Today, Lee is the official successor to the crown. This is his Cinderella story

Andrew Lee is princely, but in a modern, self-made tech-royalty sense rather than a traditional crown-and-sceptre way. His ears sparkle with diamond studs, while his shoulder-length curls are tucked under a flat-brimmed, hip-hop-style baseball cap emblazoned with the words “Handshake Hodler” – terms used in blockchain and crypto culture.

Lee, 34, also happens to be the newly crowned prince and successor to the imperial throne of Korea.

Until his inauguration in October, Lee led an existence typical to many Korean-Americans, running a tech company and raising two young children with his wife in the suburbs of Las Vegas, where the family recently relocated from Los Angeles.

But in an elaborate twist straight out of the plot of a South Korean drama, Lee’s life took a Cinderella-like turn five years ago when he found out he was related to Yi Seok, the “nominal emperor” of Korea and self-proclaimed remaining heir to the long-abolished and nearly forgotten Joseon dynasty, the region’s last monarchy, which ruled over the peninsula for over five centuries from 1392 to 1897.

Lee was born and raised in Indianapolis, the capital of Indiana, along the rust belt where only corn and other agricultural industries reign. He says his parents (his father is related to the Yi family) never disclosed their royal relations, so he only learned about the family dynasty through a passing reference from a relative. “I wasn’t aware of our family background,” Lee says.

“You don’t learn much about the Joseon empire or Korean history growing up in the US.”

He dropped out of university in his early 20s. “I don’t really have much of an educational background,” he says, adding that while he was not the best student, he had an interest in computers and coding from a young age. “I went to Purdue University, I ended up transferring to Buffalo, New York. At some point I just left school and started my work on the internet.”

Lee went on to found his own tech company, Private Internet Access – a VPN service provider in the United States. While Lee refuses to share who or how many use his services, citing user confidentiality, the firm is among the most well-known VPN providers in the world, according to user and internet search rankings.

And he has continued along this unconventional trajectory of success. A few years ago, when he finally met his relative Yi Seok, they got on so well Yi decided to make Andrew his heir.

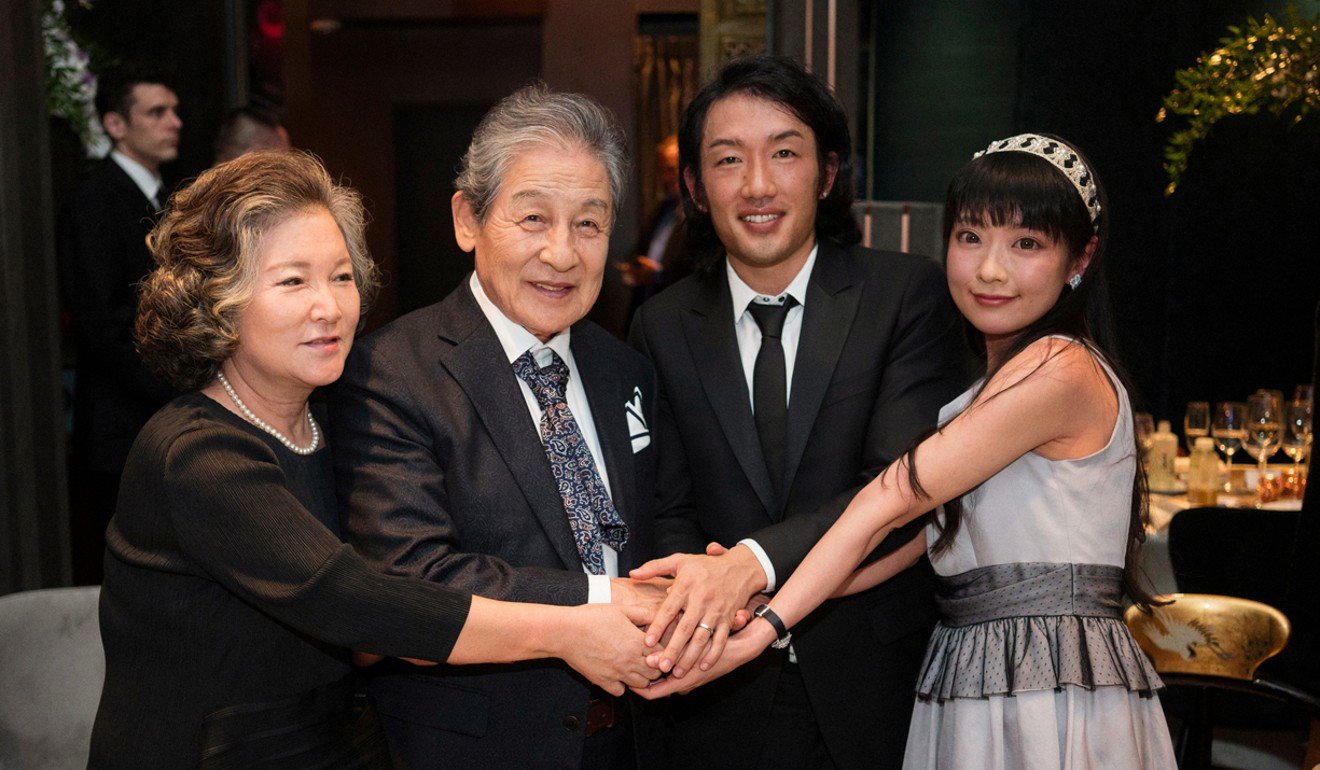

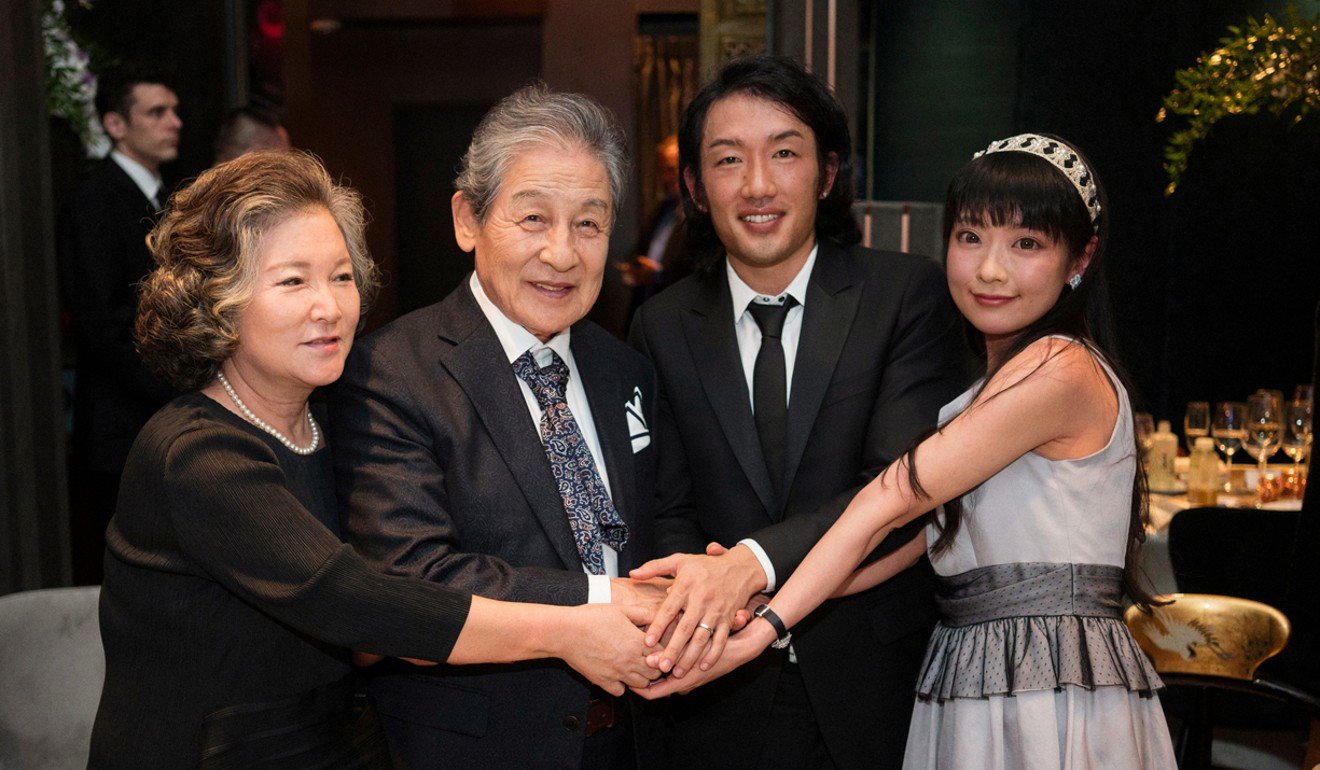

Last month, Yi held a “passing of the sword” ceremony inside the plushly orientalist decor of the Crustacean Beverly Hills, a high-end Vietnamese seafood restaurant in Los Angeles. “I will commit to the values of love, human rights, peace and freedom for humanity to the best of my ability,” Lee swore on a ceremonial sword. Those present included Korean government officials from Jeonju city, the family’s ancestral home; Los Angeles city council members; and Bermuda Premier David Burt.

I don’t go around saying ‘Hey, I’m a prince’, I stay pretty low key

“People think it’s cool that I’m royalty [now],” Lee says. “But I don’t go around saying ‘Hey, I’m a prince’, I stay pretty low key.”

And while he may be crown prince of Korea, Lee says culturally he feels more Korean-American; he has only visited his parents’ native South Korea a handful of times. Next year, however, he plans to visit Jeonju, where Yi resides.

THE SINGING PRINCE

Lee’s benefactor, Yi Seok, has led a colourful life.

Born in 1941, Yi lived in the shadows of his royal name for most of his existence. “I was born when my father Yi Kang, the second son of Emperor Gojong, was 62 years old,” he says, in an interview from Jeonju. “Being the ‘Last Prince of the Joseon dynasty’ is a burden because of our family’s long history.”

When the nation came under Japanese colonial rule in 1910, the Korean royal family was annexed and lost their official authority. As the last Joseon prince still living in South Korea, Yi was raised at Sadong Palace in Seoul, living there for the first few years of his life until the royal family was expelled from the palace following Korea’s liberation in 1945.

The family’s assets and properties became nationalised during this period, under the rule of president Syngman Rhee, who feared the royals could make a comeback.

In 1948, the Yi family was stripped of their titles and lost their formal recognition under the new constitution of South Korea. However, its remaining descendants continue to be recognised by some members of the public.

From a young age, Yi sought ways to support his family; his father passed away in the early 1950s. While studying Spanish at Seoul’s Hankook University of Foreign Languages, he realised he had a talent for singing. By the next decade, he was known as the “Singing Prince”.

“I won a prize during a singing competition and I realised I could work as a DJ and sing pop music, all the while supporting my family,” Yi says. “A composer gave me the single Dove’s Nest, and it became a big hit. Every Korean knew the song at the time,” he says, noting that it was among the top songs played at weddings during its release in 1967. “Some people still call me the ‘Dove Prince’ even now.”

This success did not last, however. Yi’s first marriage fell apart – “She didn’t like me, I was a poor prince” – and amid the political upheaval after the assassination of military dictator Park Chung-hee in 1979, Yi moved to the US to a new life. There, he cleaned pools and did other odd jobs, toiling away until the 1990s before finally returning to South Korea.

Yi was homeless for a period, until – rumour has it – a Korean reporter found him sleeping in a jjimjilbang, or bathhouse, and publicised the prince’s plight. The mayor of Jeonju offered Yi a home in his family’s ancestral town, and since then Yi and his second wife have become royal hosts. They can often be spotted in bright yellow robes, greeting the town’s tourists and visitors.

I think the government should do something for the people, and not become concerned about history

“Some people say the government should take care of the [remaining] royal family, but I think the government should do something for the people, and not become concerned about history,” he says, adding that the royal family has largely become forgotten.

Today, while most Koreans know Lee Jae-yong, the chairman and “crown prince” of Samsung, or Kim Jong-un, the self-styled supreme leader of North Korea, many Koreans – especially those who are younger – no longer know the present Yi family.

ROYAL REVIVAL

Despite his stance that the past should remain the past, Yi and his heir are angling for a royal comeback. The nominal emperor and prince are starting an imperial fund under which they will invest in emerging start-ups in South Korea.

“Our fund hasn’t officially started yet, the plan is for it to start in 2019,” Andrew Lee says. “Sometimes it’s really hard to start a business if you have a job, or if you’re a student in Korea … If you have funding to focus full-time on a project you believe in, you’ll actually make progress and be able to do that.”

Lee adds that they will also launch a coding school in South Korea called Hack Yo – “It’s kind of like saying ‘hack, yo’” – while explaining that in Korean the word hakyo also happens to mean “school”.

He likens his new role to the work of Sejong the Great, a popular Joseon king who ruled Korea in the 1400s and is best known as the inventor of hangul , the Korean alphabet, which is still used today.

Back then, it was mainly the wealthy upper classes that were literate in hanja , or Chinese characters. “You could only become rich if you could read or write. So it was a conundrum where everyone was screwed,” Lee explains. “King Sejong fixed this with the creation of hangul . In Korea now, the majority of people can read and write.”

What they want with Hack Yo, Lee says, is for everyone to how to code – which he claims is the language of the future. But at a time when young Koreans call their society “Hell Joseon” in reference to the rigid hierarchies and sorely limited social mobility that existed during the era, it’s difficult to imagine how a royal comeback and an imperial fund will be received.

Royal families can be a symbol of national pride and unity, like in the case of Great Britain or Japan, says Shin Gi-wook, a professor of sociology and director of the Korea Programme at Stanford University, but there’s no need for such a legacy in modern Korea.

“Sometimes modern societies will try to revitalise or reconstruct the past for the present, but I don’t think there is much appetite to promote royal families in [Korea],” he says, adding that the Korean royal family was often denounced as part of a bygone, passé era.

Nathan Millard, founder and CEO of G3 Partners, a Seoul-based PR firm specialising in marketing start-ups, agrees that most Koreans aren’t clamouring for a return of the nobility.

“It’s totally different from other countries that have acting royal families,” he says.

“I’m British. I like the British royal family. They are an institution and a cultural legacy of a rich history. They are a fantastic tourist attraction and a powerful diplomatic tool.

“They are also popular – the world tunes in to see them get married, or when they die.

“The Korean royal family had its time, but there’s nothing about them that is current or relevant,” Millard says. “To my knowledge there is no populist feeling about the royal family in Korea, either positive or negative, and they don’t seem to influence anything. It’s fine for them to launch a fund and support start-ups, but they have to articulate an actual value.”

Surprisingly, Yi Seok agrees that despite hanging on to his royal title, today’s Korean royalty live in a different world.

“Korean society has changed rapidly … The era when the privileged people ruled the world has gone,” he says, referencing gapjil – a slang term, referring to abuse of power, that has been trending heavily on Korean social media in light of recent public criticism of the country’s emphasis on status and privilege.

Over the past few years, politicians and public figures have been lambasted for their treatment of junior staff and customer service representatives within the nation’s extremely hierarchal society. Last year, a video of South Korean politician Kim Moo-sung went viral after he offhandedly waved a rolling suitcase to an aide while strolling out of the arrival area at Gimpo Airport in South Korea.

“There is no place for privileged people in Korea if they try to keep their privilege,” Yi says. “After all, these days, people gather in crowds on Twitter to debate what is right and wrong.”

In his successor, however, Yi sees promise for the future. “Andrew is a decent young man. He is a young entrepreneur who loves Korea … I’m 78 years old now, so this bright young man should try to do something for the people of Korea.”

Lee feels much the same way. “I don’t think there needs to be some absolute royal monarch,” he says. “Like the historical rule of our family – I don’t think this world needs that now … But at the same time I do think having a champion of the people is not a bad thing.”

So instead of being visible and spending his days atop a golden throne, Lee says becoming king means working behind the scenes to make an impact – something he hopes to achieve with the imperial start-up fund.

“I don’t want anything we’re doing to be about me,” he adds. “I’m just some dude.” ■

Additional reporting by Chaihyun Lee