‘It is modern-day slavery’: migrant workers from Indonesia’s East Nusa Tenggara face trafficking, abuse

- The impoverished province is a recruiting ground for many migrant workers, including those who are moved illegally within Indonesia’s borders

- Those seeking to return as they flee violence or exploitation turn to Antonious Remigius Abi, an ethics professor who also calls East Nusa Tenggara home

It was around 3am when Antonious Remigius Abi, an ethics professor at the Faculty of Law at Santo Thomas Catholic University in Medan, North Sumatra, was awoken by frantic knocking on his front door. When he opened it, he found six young women carrying what seemed like all their worldly possessions.

“They were begging for help, saying ‘Please protect us. Don’t tell anyone we’re here’,” said Abi, who recognised from their accents that the women were from his home province of East Nusa Tenggara (NTT) – one of the poorest in Indonesia. “They were clearly absolutely terrified.”

While their arrival on that night almost two years ago was dramatic, it was not particularly surprising. The softly spoken lecturer has become known in Medan over the past few years as the main source of support for migrant workers from NTT fleeing abuse from their employers and wanting to return home.

NTT is one of the main recruiting grounds for migrant workers from Indonesia. Domestic work is seen as a lucrative profession for many young women from the province, due in part to widespread poverty and the lack of other options. As of September 2019, NTT had a poverty rate of 20.62 compared with the national average of 9.22, according to the Indonesian Bureau of Statistics.

The exact numbers of migrant workers from NTT are difficult to source, because many of them are recruited illegally or using forged documents, but the Indonesian Migrant Workers Placement, Protection and Monitoring Agency (BP3TKI) in the province said 119 migrant workers from NTT had died in 2019 alone.

In 2018, the death of Adelina Sau, a domestic worker from the province, sparked a scandal in Malaysia after her autopsy revealed acute malnutrition and untreated, infected wounds, along with acid burns and dog-bite marks. While her 59-year-old employer was charged with murder, the case was dropped in 2019 due to a lack of evidence.

An estimated 2.7 million Indonesian migrant workers are in Malaysia, according to government statistics, though only about one-third are documented. Allegations of abuse have sparked diplomatic flashpoints between the countries, with the Indonesian Foreign Ministry in November calling on Malaysian authorities to better monitor employers and guarantee protection of migrant workers after news emerged that an Indonesian domestic worker had been beaten, cut, scalded with hot water and denied food.

OVERBURDENED AND ABUSED

Abi from Santo Thomas Catholic University became involved in helping migrant workers return to NTT a few years ago, after a migrant worker in Medan managed to contact the lecturer’s family in Kefamenanu, who in turn called him and asked for help. He has since become known as the go-to person for mistreated migrant workers, and often visits their homes to advocate on their behalf.

“I say that I’m a lecturer at the faculty of law,” Abi said, laughing. “I don’t tell them I teach ethics.”

He explains that workers are usually taken by boat from Kupang in NTT to Makassar in Sulawesi, where their phones are confiscated. They are then taken to Jakarta and on to Medan, where they are told they will receive training before flying to Malaysia. Often, they are simply sent to work with local families instead.

“Every year there are two or three new cases, usually involving more than one domestic helper. Some are underaged, maybe 14 to 16 years old. Their documents have been falsified to make them seem older,” Abi said. “In all of these cases we find one or a combination of several things. The domestic helpers are overburdened with work and can’t cope, there is psychological abuse, or there is actual physical violence.”

03:53

Domestic helpers in Hong Kong pitch in to try and stop the spread of coronavirus in the city

Yet prosecutions remain scarce. If apprehended, local recruiters in NTT often claim they thought they were recruiting for reputable employment agencies. Employment agencies in turn say they recruited the women in good faith and cannot be held responsible for the actions of employers – who deny that any abuse took place, or say they paid their workers’ salaries to the employment agencies. In the endless cycle of blame, it is the migrant workers who are left with few options other than to call someone like Abi and hope to negotiate some kind of settlement that will allow them to return home.

Dr Maidin Gultom, dean of the law faculty at the Santo Thomas Catholic University, said misinterpretations of the law did not help the situation. “It is human trafficking pure and simple, and the workers do not need to have been taken to a foreign country for that to be the case,” he said, adding that it was rarely viewed this way by the local authorities if domestic workers were employed in other parts of Indonesia.

“It is exploitation and nonsense from the employment agencies who claim that they can’t protect the workers they have themselves recruited. But there are rarely legal channels available to these women because they are seen as insignificant even though they are victims.”

“The root of the problem in NTT is the vicious cycle of poverty in villages where many youngsters drop out of school and have no work,” said Damai Pakpahan, the Indonesia director of NGO Protection International. “Another issue is that the government does not prepare domestic workers in terms of their rights and monitoring issues.”

A draft bill that would improve workers’ rights, known as the Domestic Workers Bill, has been stalled in Indonesian parliament for almost 15 years.

‘IT SCARES THEM’

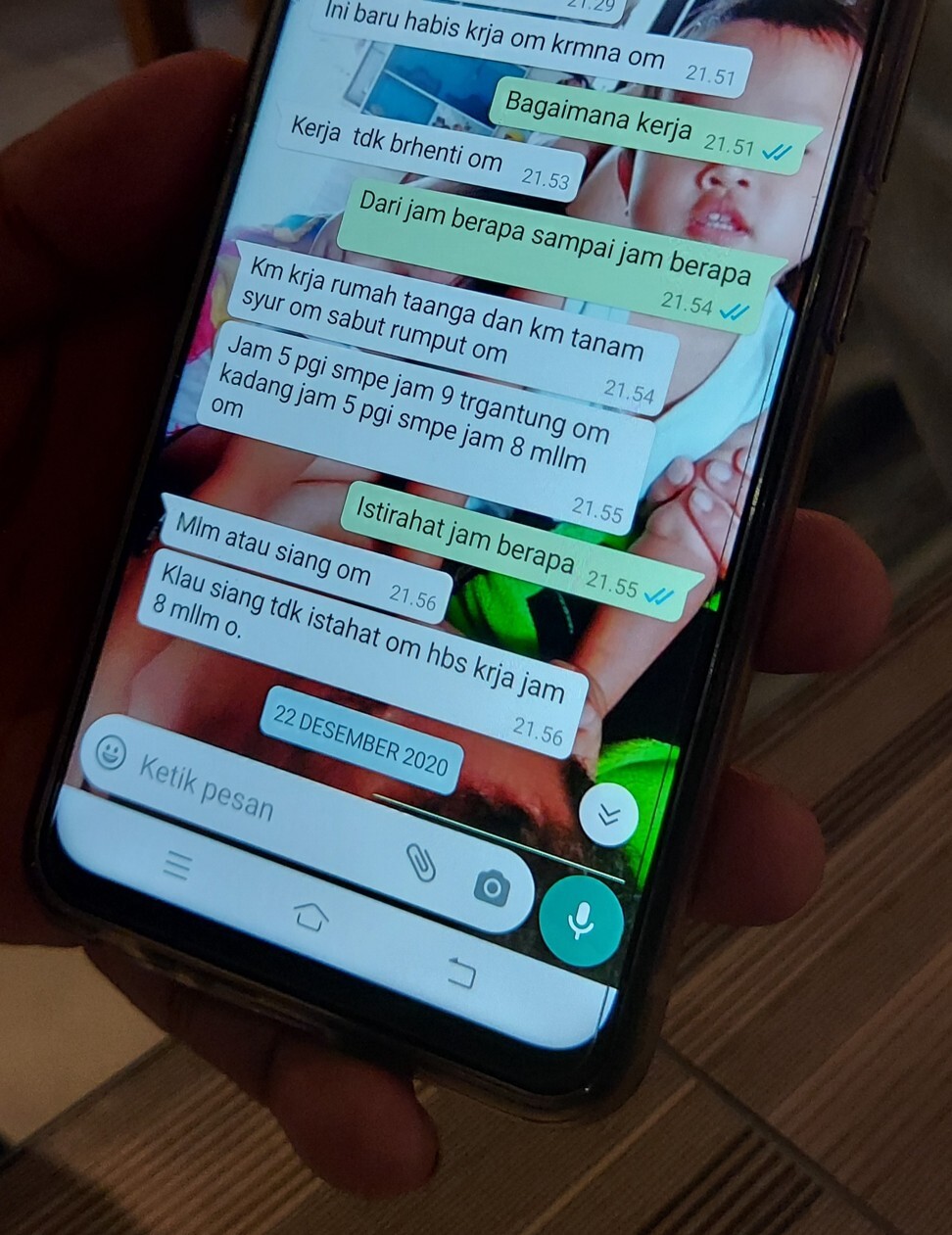

At the moment, Abi is helping a young domestic worker from NTT, Agnes – whose name has been changed to protect her identity – who has been in touch with him almost daily. He shows This Week in Asia the messages in which she says she works from 5am to 9pm every day. “She has also told me that her employer regularly abuses her verbally, calling her stupid and uneducated because she is from NTT,” Abi said.

He said he only showed up at a home after making inquiries in the neighbourhood. “In all the cases I have worked on, the information given to me by the domestic helpers has always been true, but I can’t just rush in without doing my due diligence first,” he said, adding that employers are usually shaken by his arrival.

“Their workers are uneducated kids from NTT, so they think everyone from there is like that. When they see someone from NTT who is educated and works at a university, it scares them. I use the strategy of breaking the stereotype to my advantage, to get them to listen to me.”

If they refuse to allow the domestic worker to return home, or try to withhold wages, Abi reports the case to the local authorities in NTT and the police in Medan, although going through legal channels can be challenging with the often limited evidence available.

Ranto Sibarani, a prominent human rights lawyer in Medan, has handled a number of such cases. “The abuse flourishes from the beginning. Migrant workers have no bargaining power once they go with a recruiter and they are victims before they even start work. The root of the violence comes from their lack of options and inability to find work in NTT,” he said.

“To reduce the abuse, the government needs to implement more robust regulations to punish the people who commit violence against domestic workers and we need to hear more in the media about those who have been punished, as well as the stories from the workers themselves.”

Abi is currently trying to raise the funds for a grass roots training programme in NTT that would allow former migrant workers to travel to remote villagers, share their experiences and warn others not to believe the empty promises made by recruiters.

He said he would continue to take on cases such as those of Agnes out of a sense of familial responsibility for migrant workers from the province who feel alone and isolated. In the case of the young women who found their way to his home in the early hours of the morning, the local NTT community in Medan pooled their resources to buy tickets to help them return home.

“The feeling of brotherhood among people from NTT is so strong,” Abi said. “If you hurt, then I hurt. It is called empathy. Some people in this world seem to lack it, but many of these workers are really suffering.

“It is modern-day slavery.”