Hunting Hambali: bringing ‘Southeast Asia’s Osama bin Laden’ to justice

- The Indonesian accused of masterminding the 2002 Bali bombings has been held for the past 15 years at the US military prison in Guantanamo Bay

- He remains one of a handful of high-value detainees at the facility still considered a high-risk threat to the US and its allies

Two decades after Singapore began cracking down on a pan-Southeast Asia terrorist group calling itself Jemaah Islamiah (JI), the network’s operations leader, Hambali, remains at Guantanamo Bay awaiting trial. The evidence against him shows that he took orders and money from the al-Qaeda mastermind behind 9/11 to stage terrorist attacks in the region, including the deadly Bali bombings in 2002, and was planning yet more attacks when captured in 2003. In the first of a two-part feature, Susan Sim, who was a journalist in Jakarta during the events of September 11, 2001, takes a look at his legacy of mayhem.

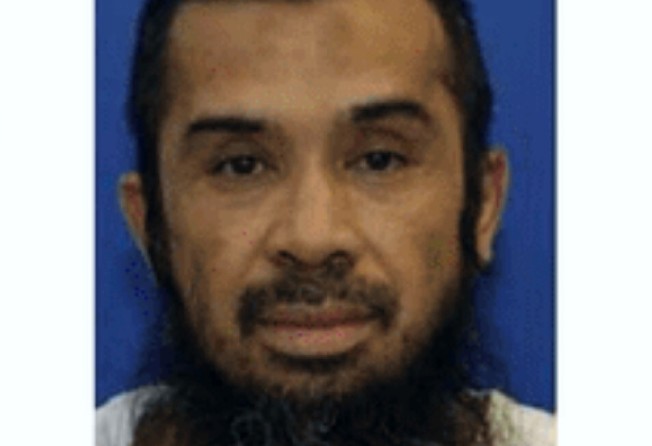

As the 19th anniversary of the 2002 Bali bombings approached earlier this year, the Indonesian accused of masterminding the attacks appeared before a United States military commission in Guantanamo Bay, where he has been held for the past 15 years.

Riduan Isamuddin, better known as Hambali, was charged with conspiring to carry out the Bali attacks as well as a suicide bombing at the JW Marriott Hotel Jakarta in 2003 that together left 213 people dead, including 88 Australians, 38 Indonesians, 23 Britons, 11 Hong Kong residents and seven Americans.

Dubbed “the Osama bin Laden of Southeast Asia” by the CIA, Hambali was captured in Thailand in 2003. Held first on the Indian Ocean island of Diego Garcia before being sent to Guantanamo Bay in September 2006, he remains one of a handful of high-value detainees at the US military prison still considered a high-risk “threat to the US, its interests and allies”.

His “hatred for the US”, steadfast support for extremist causes and promotion of “violent jihad while leading daily prayers and lectures” were highlighted in a 2016 detainee profile, which also noted that during his time in detention he had “emerged as a mentor and teacher” to fellow detainees.

I was a journalist in Jakarta in 2000 when Hambali staged his first terrorist attacks and over the years, I have both spoken to the counterterrorism officials who hunted him and former members of his terrorist network who opposed his violent agenda and dropped out.

The Hambali story is as much about international resolve to stop him as that of his efforts to terrorise the region.

‘Someone was carrying the bomb when it blew up’

General Gories Mere has never forgotten his first suicide bombing investigation. When we met on the eve of the 10th anniversary of the Bali bombings, Indonesia’s top counterterrorism police officer was about to retire.

He had many stories to share, but perhaps because a credible terrorist threat had been made against the commemorations, the 2002 attacks were at the forefront of his mind.

As the Indonesian police’s top troubleshooter even then, Gories was tasked with uncovering who was behind the bombings in the Kuta tourist district on the night of October 12, 2002.

No group had claimed responsibility for the attacks. To identify the culprits, Gories and his task force would have to uncover the attack modus operandi. How, for instance, did the terrorists get the first bomb into Paddy’s Bar?

The Indonesian police did not then have advanced forensic capabilities, and since a bomb had also been detonated outside the US consulate in Denpasar that night, the US offered the assistance of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

A few days after the attack, Gories watched as several FBI bomb scene specialists reconstructed the blast trajectories to determine where the bomb had been placed in Paddy’s Bar when it detonated.

The trajectories converged at a spot about one metre (3 feet) above the broken ground. Was there a high table or bar stool there, Gories asked one of his investigators? The officer consulted a crime scene diagram and replied: “Tak ada meja atau kursi di sana, pak [There was no table or chair there, Sir].”

“The bomb exploded in mid-air,” Gories recalled of the moment he realised a suicide bomber had struck Paddy’s Bar, shock still reverberating in his voice despite the passage of time.

“Someone was carrying the bomb when it blew up.”

A human head and parts of a right leg and a left leg had been found near the bomb crater. A forensic pathologist among the growing army of foreign experts examining the scene had established the parts were from the same person. Gories now knew no one had identified the body because it was that of the suicide bomber.

Indonesia had now become the 21st country to be struck by suicide bombers since the tactic was first used in Lebanon in 1981.

Until the Bali blasts, most Southeast Asian observers believed suicide bombing to be culturally anathema even to Indonesian extremists. Jihad, yes, but blowing oneself up to kill others?

No way, everyone said. Even al-Qaeda had decided not to rely on local talent to carry out the wave of truck bombings it was planning in Singapore after the 9/11 attacks; the locals were in charge of reconnaissance and procuring the explosives, but the six suicide bombers required were to be selected from among its Yemeni and Saudi operatives.

Gories learned later that Indonesia’s first suicide bomber was a young man from Central Java who went by the name Iqbal.

Never fully identified to this day, Iqbal sent hundreds fleeing into the streets of Bali, to be maimed and slaughtered by another suicide bomber in a white van laden with 950kg (2,000lbs) of explosives outside the Sari Club across the street from Paddy’s Bar.

By zeroing in on a crucial lead – the discovery of the vehicle identification number of the white van led to a name that matched one in a photo album that one of Gories’ deputies had compiled from interviews with militants detained by the Singapore internal security service – the Bali blasts task force eventually caught most of the men who built the bombs, selected the targets, and dispatched the suicide bombers.

Those arrested confirmed what most counterterrorism specialists had suspected as soon as the bombs went off – Hambali was behind the attack.

‘The Osama of Asia’

Riduan Isamuddin was 21 when he left his hometown of Cianjur in Indonesia’s West Java province to look for a job in Malaysia in 1985.

He married a Malaysian Chinese woman who had converted to Islam and joined a mosque, where he would later claim he was “brainwashed” into pursuing jihad (holy war) by the exiled leader of Indonesian rebel group Darul Islam.

Within a year he was in Afghanistan, where he first received military training and fought for 18 months alongside other foreign fighters to liberate the country from Soviet occupation.

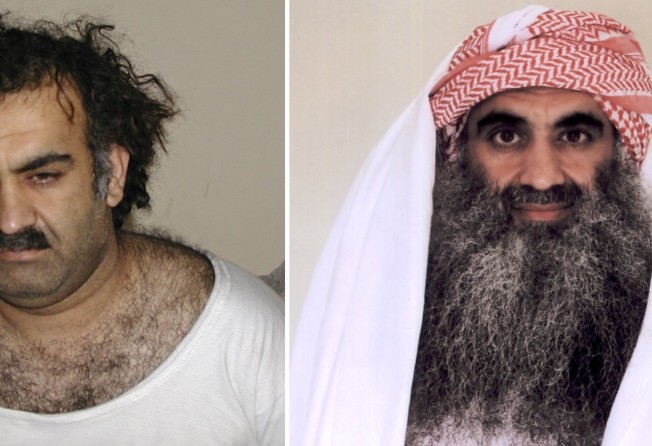

Here he adopted the nom de guerre Hambali and formed a bond with fellow foreign fighter Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM), a Pakistani militant he would keep in touch with even after leaving Afghanistan in 1988.

Darul Islam sent some 200 Indonesians to what was known as the Afghanistan Mujahideen Military Academy between 1986 and 1995. Hambali was not a top trainee nor destined to become one of Darul Islam’s leaders.

He instead aligned himself with a splinter group favoured by the Afghan veterans called Jemaah Islamiah (JI), and travelled across Southeast Asia establishing links between it and other militant groups and promoting extremist violence.

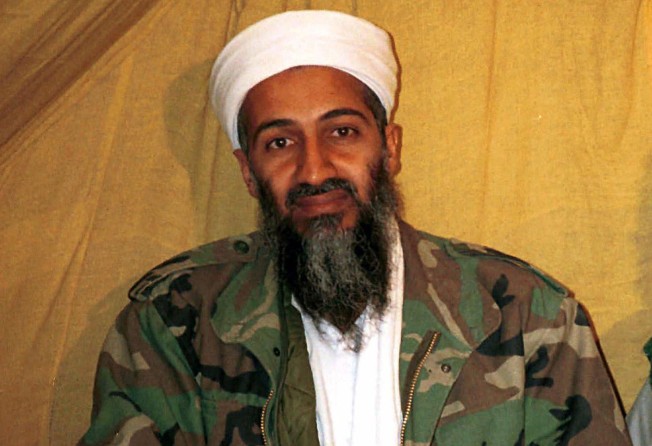

Hambali’s friendship with KSM – who would later be described by the US as the principal architect of the September 11 attacks – not only gave him access to al-Qaeda funds, but to the group’s leader.

In 1996, he was invited to spend three or four days with Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan, after which it was agreed that al-Qaeda would work with JI on “targets of mutual interest”.

Following his capture in 2003, KSM told American interrogators that he found Hambali to be “charismatic and popular”, with “loyal and well-prepared” recruits whose main targets of attack were Australia, the US, Britain and Israel.

KSM described Hambali as “a trusted and respected operative”, but said al-Qaeda’s relationship with him and JI was “determined by need”.

If al-Qaeda operatives needed to visit Southeast Asia, Hambali would help sort out the logistics – even arranging a flat in Kuala Lumpur for KSM to use so he could meet with two of the September 11 hijackers before they left for the US to begin flight school training.

When Hambali proposed opening a second front in al-Qaeda’s war on America by attacking US civilian and military targets in Southeast Asia, KSM sent him funds and advisers, and promised him suicide bombers.

Soon after the September 11 attacks, an al-Qaeda operative travelled to Singapore to direct local JI members on a plan to attack the US embassy and several other high-profile targets in the city state using truck bombs.

The plan was foiled following an informer’s tip-off, which led Singapore’s Internal Security Department to mount one of the largest operations in its history with the aim of uncovering the terrorist network.

JI members arrested in December 2001 named Hambali as the leader of the group’s Singapore and Malaysia arm, called Mantiqi 1 – though Hambali was operating throughout the region.

Hambali was soon also wanted in the Philippines for planning the bombing of passenger trains in Manila in December 2000, in Indonesia for organising the bombing of Christian churches on Christmas Eve of that same year, and in Malaysia in connection with bank robberies by militants linked to JI. The US also wanted to question him about his connections to KSM.

After the Singapore arrests, Hambali gathered what was left of his network in Malaysia and instructed them to retaliate against the country.

One five-men cell went so far as buying tickets for a flight out of Bangkok that they intended to hijack and crash into Changi Airport, but the plan was aborted after an aviation alert was sent out by Singapore authorities and the cell’s leader saw his name in the press.

Thwarted again, Hambali summoned his cell leaders and bomb makers from Malaysia and Indonesia to a meeting in Bangkok in early 2002. With the promise of al-Qaeda funding, he told them to find soft targets elsewhere in the region, such as bars, cafes and nightclubs frequented by tourists.

By his own account, Hambali received at least US$86,000 from al-Qaeda to fund JI attacks in Southeast Asia – money he jealously guarded.

Nasir Abas, who ran JI’s training camps in the Philippines in the late 1990s before deciding to leave the group after the Bali bombings, remembers Hambali refusing to give him money to buy computers for his camp.

“But if I had a plan for bombing churches in Kota Kinabalu, he would have found the money,” Nasir, who now works with the Indonesian police to deradicalise extremists, told me.

“He had no money for training. But for operations, he’d find money in one night.”

Hambali himself led a frugal life on the run. At the time of his capture, he was living in a flat in Thailand with no air conditioning that cost him US$60 a month in rent.

Thai investigators found only fresh eggs in the flat, and learned from Hambali’s wife that he would walk to the nearby 7-Eleven to buy eggs and cook all their meals at home. About the only thing of value he ever gave her, she said, was a pair of gold and diamond earrings.

By some estimates, the 2002 Bali bombings cost about US$35,000 to execute – including money for a van, bomb-making materials and renting safe houses where the explosives were assembled. In addition to the funds provided by Hambali, the terrorist cell also raised money by hacking computers and robbing a jewellery shop.

Originally planned for September 11, 2002 – to mark the first anniversary of al-Qaeda’s attack on the US – the Bali bombings were instead delayed until October 12 because the explosives were not ready in time.

Pleased by the attack’s “success”, KSM sent Hambali another US$50,000 for the next operation, and to help the families of those arrested. His courier was a Pakistani named Majid Khan who had studied in the US.

Most of that cash went towards financing the attack on the JW Marriott Hotel in Jakarta in August 2003, Hambali acknowledged under interrogation. But by then a Malaysian named Noordin M Top was making a bid for Hambali’s mantle as Indonesia’s most dangerous terrorist.

Susan Sim is a former journalist, intelligence analyst and diplomat who served as Singapore’s deputy chief of mission at its Washington DC embassy from 2003 to 2006. She is currently vice-president for Asia with The Soufan Group, a global strategic consultancy, and Adjunct Senior Fellow with the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore