Singapore’s George Yeo on Southeast Asia’s Chinese diaspora, regional anti-Chinese sentiment, and Lee Kuan Yew’s US-China calculations

- The ex-foreign minister believes the relationship between China and Singapore’s Chinese diaspora will strengthen as Beijing’s influence in global politics and economics grows

- Singapore’s ‘Chinese-ness’ can be appealing to diaspora communities, but city state is conscious that Asean neighbours could view it as ‘an agent of China’, he adds

For half a year, Singapore’s former foreign minister George Yeo met and mused over a wide range of topics with writer Woon Tai Ho and research assistant Keith Yap, in weekly interview sessions which lasted two to three hours each time. The result of the interviews is a series of three books. In the first book, George Yeo: Musings, the 67-year-old offers his views on India, China, Asean, Europe, the United States and other parts of the world, and how Singapore’s history and destiny are connected to all of them. In this excerpt, Yeo addresses Singapore’s strong diasporic links with China, its relationship with the mainland and regional suspicions about these ties.

How will Singapore’s connection with China affect its ties with other countries?

As China moves to centre stage in global politics and economics, the relationship between China and the Chinese diaspora will naturally grow stronger. Chinese communities which lost their connection to China (like the Peranakans of Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore) are finding renewed interest in Chinese heritage and language. For generations, the Peranakans of Singapore and Malaya developed their own subculture.

They were self-consciously Chinese but looked down on new Chinese migrants, whom they called the sinkeh (新客). Peranakan food is a favourite cuisine among Singaporeans and Malaysians. The fastidiousness of their womenfolk is expressed not only in their food and dressing but also, and especially, in their jewellery.

When in mourning, the women wear only silver jewellery as gold is reserved for celebrations. In 1993, Edmond Chin put together a delightful exhibition called “Gilding the Phoenix” at the old Tao Nan School, which became a part of the Asian Civilisations Museum.

Many of Singapore’s first generation of leaders including Lee Kuan Yew, Goh Keng Swee and Lim Kim San were Peranakans. With the rise of China, Peranakans are reconnecting to their mother culture. This creates new tensions.

In the US today, American-Chinese working in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) have suddenly found themselves under surveillance or suspicion by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) because of worsening relations between the US and China.

In 2018, the director of the FBI, Christopher Wray, said the US was concerned with “the China threat as not just a whole-of-government threat, but a whole-of-society threat on their end”, which required “a whole-of-society response by us”.

In a speech at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in January 2022, Wray stressed again, “I want to focus on it here tonight because it’s reached a new level – more brazen, more damaging, than ever before, and it’s vital, vital that all of us focus on that threat together”.

In Southeast Asia, ethnic Chinese have gone through difficult periods in the past. After South Vietnam fell to the North in 1975, the first waves of boatpeople were mostly Chinese.

Under Suharto, Indonesia banned Chinese language and literature, probably the only country in the world to do such a thing. I remember reading with disgust customs forms which stated that, along with drugs and firearms, Chinese-language material was also considered contraband. In Thailand, those of Chinese descent were not allowed to join the army (although many still did).

Anti-Chinese sentiment

The main cause of anti-Chinese sentiment in Southeast Asia is the disproportionate role ethnic Chinese play in business. Among the very wealthy, many are ethnic Chinese. Some are known for their philanthropic work like Lee Kong Chian’s family, but a few behave badly and live ostentatiously. Thailand’s King Rama VI criticised the ethnic Chinese as the “Jews of the East” even though his own ancestor, Rama I, had Chinese blood.

They are also seen as being disloyal or not loyal enough. Overseas Chinese supported China’s resistance against increasing Japanese encroachment into the Chinese mainland from the early 1930s.

Tan Kah Kee organised the Nanyang Federation of China Relief Fund Technicians. From 1939 to 1942, over 3,000 overseas Chinese volunteered as truck drivers and mechanics in China along the Rangoon-Yunnan Road. About 1,800 technicians died from bombing, disease and exhaustion.

His nephew, Tan Keong Choon, raised money to build a memorial by Dian Lake near Kunming to remember their sacrifice. At the Ee Hoe Hean Club in Singapore, there is an interesting memorial hall to Tan Kah Kee and other Singapore-Chinese leaders.

Japan viewed overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia as extensions of China. Japan’s invasion of Southeast Asia was carefully planned for years before it was executed in December 1941. Plans for the Malayan Campaign were made in Taiwan (which Japan took from Qing China in 1895).

In his book, The Killer They Called a God, Ian Ward writes about how Lieutenant Colonel Masanobu Tsuji drew up a detailed plan to eliminate many overseas Chinese once the Japanese army had occupied Singapore. Post-war sources revealed that the order was to kill 50,000. The Japanese referred to the Sook Ching as the Kakyō Shukusei (華僑粛清), meaning purging of overseas Chinese. Sook Ching was second only to Nanjing in the cruelty inflicted on a civilian population.

During the Japanese occupation of Malaya, the Malayan Peoples’ Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), led by the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM), fought a guerilla war against the Japanese in the jungle. They were mostly Chinese. Between the Japanese surrender on August 15, 1945, and the return of British forces in September that year, the MPAJA took action against Japanese collaborators, many of whom were Malay.

Ultimately, the failure of the CPM struggle in Malaya was due to their inability to win over the Malays, who expressed their nationalism through the United Malays National Organisation (Umno).

The Malayan Emergency will eventually be seen in the historical context as a nationalist struggle which failed because of racial division which the British exploited. Many young men lost their lives in pursuit of a righteous cause. Robert Kuok burns a joss stick every day for his second brother, who was killed by the British during the Emergency and whom he admired for his good-heartedness, brilliance and eloquence.

The Straits Times had a photographer, Sim Chi Yin, who accompanied me on a number of overseas trips when I was a minister. On one such trip to Hong Kong, I bumped into her in Stanley one evening. She told me that she had an exhibition on the Emergency. When I asked her about the reason for her interest, she said that it was the story of her grandfather, who had been banished to China during the Emergency and killed by the Kuomintang (KMT). The exhibition was titled “One Day We’ll Understand”.

In both Malaya and Singapore, the British were determined to hand power over to credible nationalist groups who were less unfriendly to them. In Malaya, the proposal for a Malayan Union was changed to one for the Malayan Federation, enshrining the position of the sultans and Malay rights.

In Singapore, the British favoured Lee Kuan Yew and his faction in the People’s Action Party (PAP). Both direct and indirect British interventions at critical moments were decisive. The British did not want an independent Singapore because it could become a satellite of China. They manoeuvred for Singapore to gain independence through the merger with Malaysia.

Lee Kuan Yew later said that Sarawak and Sabah were the dowry the British gave to [Malaysia’s independence leader] Tunku Abdul Rahman to admit Singapore into Malaysia. When the Tunku agreed two years later that Singapore could go free, Lee Kuan Yew wrote that he kept it a closely-guarded secret from the British until it was irreversible because they would have thwarted it.

Although many ethnic Chinese in Southeast Asia threw themselves into nationalist struggles against the colonial enemy, like the Philippines’ José Rizal, as a group they were sometimes seen to be less supportive, as in Indonesia, or too aligned with China-backed communist movements, as in Thailand and Malaya. When, for whatever reason, countries in Southeast Asia are unhappy with their indigenous Chinese populations, they project their unhappiness on Singapore as a headquarters for Southeast Asian Chinese.

Regional suspicions about Singapore

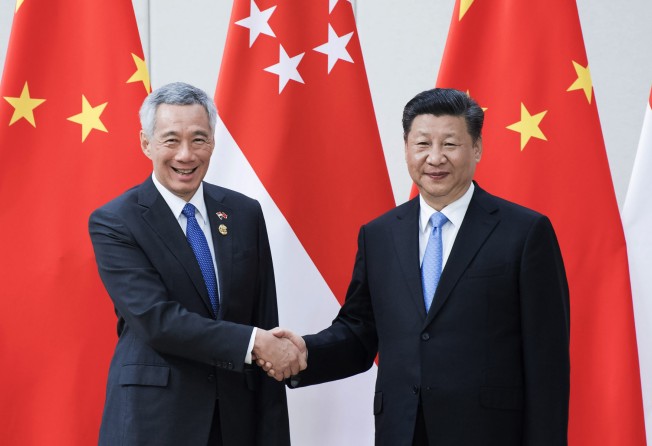

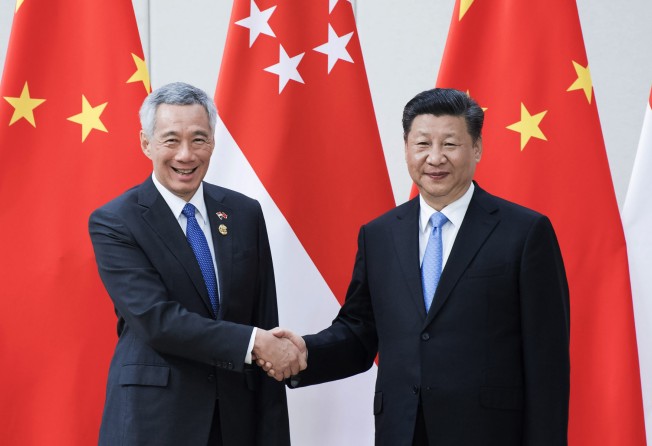

Whatever we say or do, the fact is that many countries factor Singapore’s Chinese-ness into their planning and calculations. For this reason, Lee Kuan Yew held back diplomatic relations with China until Indonesia had done so. To some extent, we have succeeded in convincing other countries that while Singapore has close cultural ties to China; on political matters, we calculate in our own self-interest.

One day in the mid-1990s, Singapore’s relations with China went through a bad patch. Indonesian Foreign Minister Ali Alatas expressed his concern about the state of Singapore-China relations to me, and indirectly offered his assistance. I was pleasantly surprised that here was Indonesia worried that we were having bad relations with China.

For a period, Vietnam viewed us with suspicion, too. After Vietnamese divisions moved into Cambodia in 1978, Singapore, together with other Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) countries, worked with China to support anti-Vietnam forces in Cambodia. (Unlike China and Thailand, Singapore kept a distance from the Khmer Rouge but supported all other factions.)

At the United Nations and other international gatherings, we combined efforts to deny legitimacy to the government in Phnom Penh installed by Vietnam. After 10 years, Vietnam withdrew from Cambodia. They then decided to follow China in gradually opening up its economy.

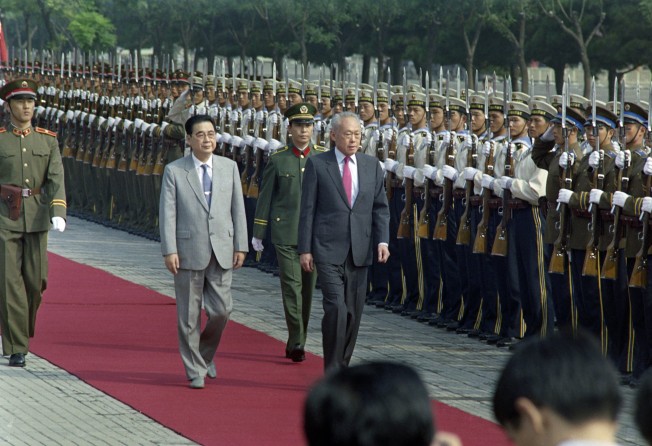

Prime Minister Vo Van Kiet visited Singapore in 1991. At the end of a dinner hosted by Lee Kuan Yew at the Istana, Kiet asked Lee Kuan Yew to be an adviser to Vietnam. Although he was taken aback and promised to visit Vietnam regularly, he did not agree to become an adviser.

I accompanied Lee Kuan Yew on his first three trips to Vietnam. Relations steadily improved. The first Vietnam Singapore Industrial Project (VSIP), was a mini-Suzhou, established near Ho Chi Minh City in 1996. (Since then many VSIPs have sprouted across the length of Vietnam.) When I was Minister for Trade and Industry, I co-chaired a bilateral commission with the Vietnam Minister for Planning as my counterpart. Whenever meetings were held in Hanoi, I called on PM Phan Van Khai. He was always polite but somewhat formal until, one year, he spoke to me as if I was his minister and started giving me “homework”.

Something had happened. My belief was that Vietnam had come to the conclusion that Singapore was not an agent of China and could become a strategic partner. On Khai’s next visit to Singapore in 2004, the two countries launched the Connectivity Initiative, which I helped put together for Goh Chok Tong.

Will the suspicions ebb eventually?

I doubt so. Chinese-ness is an inseparable part of Singapore. Others believe and expect that so long as Singapore’s core interests are not affected, Chinese-Singaporeans are likely to view China with greater sympathy.

Some of my Chinese Singaporean friends who are critical of China nonetheless get upset when they see Western countries finding fault with China. Singapore’s one-China policy is not merely a decision. The position that Taiwan is part of China and only separated because of Japan up to 1945 and the US after that is widely held by older Chinese-Singaporeans.

A Singapore government that departs from this policy is likely to face strong opposition from the majority of older Chinese-Singaporeans. In 1989, I was asked by Lee Kuan Yew to announce in Parliament that Singapore would allow US military forces in the Pacific to use our base facilities after the closure of Clark Air Base and Subic Bay.

Without the US, Singapore could not be sure that the Straits of Malacca and Singapore Strait, which are our lifelines, would always be kept open. Lee Kuan Yew was, however, very clear that should there be conflict between the US and China over Taiwan, Singapore would not be involved. I don’t believe that position has changed despite close defence links between Singapore and the US.

Chinese communities everywhere in Southeast Asia are conscious of their “Jewish” status. Anti-Chinese sentiments have generally subsided but they are still there in the soil. In countries where bad experiences are more recent, a certain sense of insecurity is pervasive, like background music. Singapore is a safe harbour they know they can turn to in a crisis. In Singapore, they can celebrate their Chinese-ness without worrying that some may take offence. However, there are a few who worry that if Singapore emphasises its Chinese-ness too much, they might be negatively affected. In my years as minister, I was conscious of this dynamic.

During my time at the Ministry of Information and the Arts, one of my missions was to promote Singapore’s diverse heritage, including our Chinese heritage. An Indonesian scholar of Chinese descent whom I know well whispered to a Singaporean friend of mine that he was uncomfortable with what I was doing.

That was during the Suharto years when Chinese language and culture were suppressed in Indonesia. At the launch of the Chinese Heritage Centre in 1995, Mochtar Riady, an Indonesian-Chinese tycoon and a member of the Advisory Board, came for the first meeting chaired by Wee Cho Yaw. He told the meeting that he received a phone call the day before from the Indonesian Home Minister asking him why he was going to Singapore for the meeting. It was a hint which he happily brushed aside.

In 1998, Indonesia was shaken to its core by the Asian financial crisis. Shadowy figures orchestrated racist attacks on Chinese-Indonesians. Many fled to Singapore and stayed here for months. I used to go running along East Coast Park and I remember seeing many of them taking evening strolls – women with their children and helpers in tow looking out to the sea.

Two years later, at a Ministry of Trade and Industry event, we invited the Indonesian scholar who had been uncomfortable with my promotion of Chinese heritage to give an in-house talk on the Indonesian economy. Before he began, he expressed his gratitude to Singapore for our assistance to Indonesian Chinese in their darkest hour of need, choking on his tears.

Who we are is not only who we think we are, but also how others see us. We have to be aware of the games which big powers play, whether to influence us or to sow seeds of suspicion here.

George Yeo: Musings is available at all major bookstores in Singapore and Hong Kong from September 2022.