New Indonesian-Chinese ‘kya-kya’ market a cultural and tourism hub for Surabaya

- The port city has often had a Chinatown market but discrimination against Chinese people over the centuries has meant a ‘kya-kya’ was not a given

- Now a new weekend night market has opened, with local government backing and halal Chinese food to appeal to the Muslim-majority population

Silvia Gunawan’s 13km journey from her home in the western suburbs of Surabaya to the Indonesian port city’s northern area was marred by heavy traffic and took an hour, but she was not fazed.

The Chinatown night market, an initiative to promote the area’s Chinese heritage, was relaunching to great fanfare on September 10, and the 39-year-old did not want to miss it.

Known locally as “kya-kya”, it had been closed since 2005. After a mammoth launch back in 2003, the then privately-run night market opened to foodies every day of the week before closing down, seemingly due to dwindling sales.

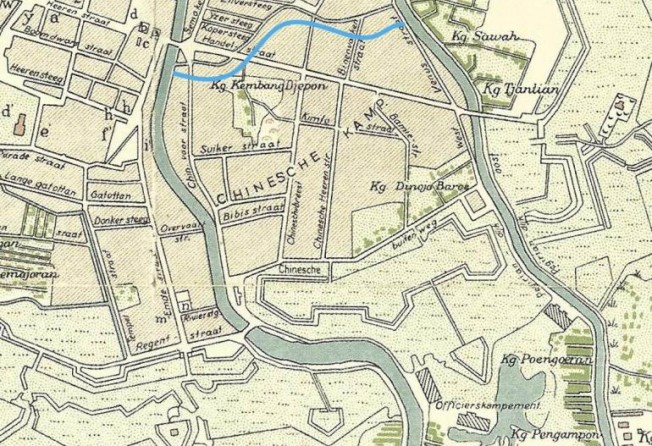

In the daytime, though, the street is – and has been for hundreds of years – full of bustling shops, a thriving thoroughfare in a Chinatown dating back to Dutch colonial times.

“It was quite a long drive, but I was curious to see kya-kya again,” said Gunawan, whose mother and teenage daughter had also tagged along to enjoy the revamped weekend-only market, which is, this time around, backed by the local government.

The term kya-kya is Hokkien in origin, meaning “walkabout”, to denote a sprawling night market where alfresco stalls sell culinary delights and other trinkets associated with Chinese culture.

Putra, 28, who lives in the southern part of Surabaya, had also driven across the Muslim-majority city with his wife and two toddlers. “I came for the food, mainly. My wife saw the announcement of kya-kya’s relaunch on Instagram,” he said.

The grand opening of the new night market saw the always popular Kembang Jepun area packed with thousands of people checking out the dozens of food stalls open for business.

The mayor of Surabaya, Eri Chayadi, declared kya-kya officially open.

“To differentiate from the old kya-kya market, the new market is a local government initiative and the food on offer is the halal version of Chinese cuisine. This was deliberate so the market can have a broader mass appeal,” said local land and housing official Iman Krestian, involved in the project because the land the market operates on comes under his jurisdiction.

He said the revival of kya-kya was based on the mayor’s vision of economic empowerment and local tourism. “We’ve made it mandatory for tenants at the market to employ local people. We hope the initiative will benefit those who live around the area,” said Krestian.

Kya-kya was also a push to entrench Chinatown and the history of the city’s ethnic Chinese as part of Surabaya’s cultural identity, he said. The Chinatown experience would include tours on becak (rickshaw) of nearby Chinese heritage landmarks such as the Boen Bio Confucian temple and the Han family ancestral shrine, Iman said.

Freddy Istanto, chairman of the Surabaya Heritage Society and also executive director of the 2003-2005 market, said he was delighted the new kya-kya would operate as part of a government initiative.

“It goes to show how attitudes have changed within government circles when it comes to accommodating Chinese culture,” he said.

He recalled how the idea of a Surabaya Chinatown had been nothing short of revolutionary back in the 2000s. The immediate years after the ouster of President Suharto in 1998, Istanto explained, gradually saw the re-emergence of Chinese culture in Indonesia.

During Suharto’s authoritarian 32-year rule, Chinese cultural expressions had been banned, including the use of Chinese names by Indonesian-Chinese. Discriminatory laws meant ethnically-Chinese Indonesians were treated as second-class citizens or worse, entrenching ethnic hatred that had been around for centuries.

It was not until 2000 under President Abdurrahman Wahid that public celebrations of the Chinese Lunar New Year festival were again allowed in Indonesia. Two years later, President Megawati Sukarnoputri declared the occasion a public holiday.

“When we first put forward the idea of resurrecting Chinatown in 2003, there was a lot of opposition to it from the authorities. We presented it to the municipal council and it was shot down immediately,” said Istanto.

During the Dutch colonial period, which ended in 1942 when Japan invaded Indonesia, Kembang Jepun, officially known as Handelstraat (Trade Street), was the thoroughfare which divided the Chinese district from the Malay Kampoong area. The zone around the street was known to many, possibly even before the war, as Kembang Jepun (Japanese Beauty) due to the proliferation of Geisha bars in its vicinity.

Istanto said re-establishing Kembang Jepun as an unmistakably Chinese landmark back in 2003-2005 was the brainchild of media tycoon Dahlan Iskan, who owns the Jawa Pos Group. Dahlan in turn asked Istanto to become his collaborator in the privately-funded project.

“After the council poured cold water on our idea, we decided to press ahead discreetly. The dragon gates had to be constructed in secret and we decided to have them installed on the site after midnight in a hush-hush operation,” Istanto said.

The new face of Kembang Jepun was presented to the city of Surabaya in 2003 on the 710th anniversary of the foundation of the city. The kya-kya project, Istanto claimed at the time, would quickly become a city icon due to plenty of media attention, endorsements from well-known people, and, more importantly, funding from the city’s 50 most prominent Indonesian Chinese businesspeople.

“Most Indonesian-Chinese figures I talked to at the time were supportive of the project,” said Istanto. “There was a longing for Chinese cultural visibility. But at the same time, we were worried about possible adverse public reactions, too.”

But their fears of a public backlash proved to be unfounded. Kya-kya had a phenomenal run for two years with over 400 hawkers at its height, Istanto said. “Kya-kya became an icon precisely because it was unequivocally Chinese.”

Since then, the idea of Chinatown has become more mainstream, leading to this year’s market relaunch.

Stall owner Tjahjono Harjono, an Indonesian-Chinese and chairman of the Indonesian Association of Restaurateurs (Apkrindo), was optimistic the 2022 night market would become a new culinary hub for Surabaya.

He said 50 per cent of kya-kya tenants are Apkrindo members and they had seen record sales on the first two nights. “There was also a lot of interest in non-halal fare so we may rise to the challenge by devoting a special section to pork dishes.”

Istanto cautioned that the new kya-kya, despite its inclusive aspirations, must never abandon the cultural idiosyncrasies that make a Chinatown.

“The Chinese attributes are the ‘genius loci’ (protective spirits), creating a distinctive atmosphere. Without them, it becomes just another place to hang out,” he said.

Istanto added that, given the popularity of online food ordering services in Surabaya today, the new kya-kya faces considerable challenges.

But Krestian said the new market will be constantly assessed and improved to ensure its sustainability.

“We are cautiously optimistic, which is why for the time being it is only operational at weekends.”