Can China ever move on from Mao Zedong?

Strands of Maoist thought are re-emerging forty years after the chairman’s death, raising fears that official ambiguity on his legacy has left the soil of revolution fertile

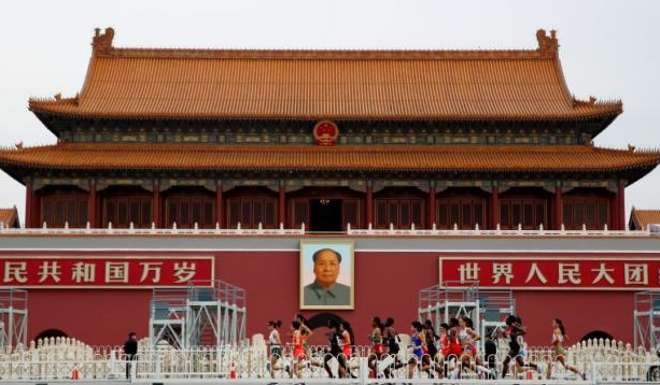

For half a century, Mao Zedong ( 毛澤東 ) has stared down at the throngs who visit Tiananmen Square.

In what is one of the world’s most recognisable portraits, his gaze meets visitors straight on – as it has ever since October 1, 1967, at the height of the Cultural Revolution.

Over the years the portrait has become an archetypal image of the former chairman of the Communist Party of China, yet what many of those who visit today may not appreciate is its subtle difference to an earlier portrayal that once hung in its place.

That version, a side-on portrait showing only the left side of Mao’s face, fell out of favour due to fears it suggested he heeded and trusted only one side. Far better the version that remains today, in which Mao looks straight forward, both ears visible, open to all sides.

This more open image of Mao, presented at China’s symbolic hub of power, is quite different to how the party described him in 1981.

“He gradually became proud and disconnected from reality and the people. His subjectivism and arbitrary style deteriorated, and he became above the central leadership of the party,” said an official resolution giving a verdict on Mao’s rule during the revolution.

“[This] impaired and damaged the collective leadership of the party and the state.”

Friday marked the 40th anniversary of Mao’s death, which brought about the end of the Cultural Revolution, a decade of social and political upheaval when the personality cult surrounding Mao and his political teachings were at their peak.

But four decades on, China is still struggling to come to terms with the legacy of a man who is printed on 100 yuan bills yet elicits mixed feelings across the country.

Admirers, many of whom celebrate Mao’s birth in his hometown Shaoshan, Hunan ( 湖南 ) province, every year in a carnival-style parade, pay him a deference that befits a god.

They are among the growing minority of Chinese who feel nostalgia for the Mao era. Support for his ideas have spread beyond laid-off workers and the uneducated poor to younger generations born after his death, even those educated overseas.

This support is often rooted in disappointment at a country that displays one of the world’s biggest wealth gaps and rampant corruption, for which Maoists blame market reforms and the intrusion of Western values.

Critics of Mao, on the other hand, see him as a merciless and Machiavellian dictator who was indifferent to the loss of countless innocent lives in order to achieve his political goals, who uprooted traditional culture and purged intellectuals along with his colleagues.

The Cultural Revolution, which Mao is said to have seen as one of his two greatest achievements, has been compared by critics to a campaign by the First Emperor of Qin more than 2,000 years ago, when he ordered soldiers to burn historical books and bury scholars alive.

To many, the party’s attitude towards Mao and his legacies is as clear as mud. The 1981 resolution, under the watch of Deng Xiaoping ( 鄧小平 ), said that “70 per cent of his work was right and 30 per cent was wrong”. It credited Mao for laying the foundation of China as a modern state, including the basic developments of industry and agriculture. It also praised him for thawing ties with the West, which had boycotted the communist state for decades.

The resolution’s political undertones were more ambiguous, with it holding him responsible for starting and leading the Cultural Revolution, which it said was a “catastrophe” and “not social progress in any sense”.

The party was unequivocal about ridding the country of his legacies, pulling down countless Mao statues across the country, jailing revolutionary fanatics and embracing foreign investment.

While the resolution contained unprecedented criticisms of Mao, it also tried to contain the damage to his image, claiming that much of the wrongdoing had been done “behind his back”. Instead, it blamed Lin Biao ( 林彪 ), Mao’s handpicked successor, and the Gang of Four, led by Mao’s wife Jiang Qing ( 江青 ), despite a wide acceptance among scholars that those people owed their power to Mao’s endorsement.

The danger of insufficient reflection regarding Mao’s legacy after all these years is alarming even to elites within the party, who firmly support one-party rule.

Zhang Musheng, considered among the influential ‘princelings’ – the children of veteran communists from before the revolution who retain powerful connections with the top leadership – is among them.

“Mao was definitely wrong about the philosophy of struggle,” said Zhang, who, like many who grew up reading the chairman’s works, can quote Mao on his philosophy of struggle: “To struggle with Heaven, the joy is boundless! To struggle with earth, the joy is boundless! To struggle with people, the joy is boundless!”

Zhang said that despite the party’s focus on economic development, in its incomplete reflection on his legacy, it had failed to question his reasons for starting the revolution.

The problem of over-concentration of power – recognised by Deng as the cause of political mayhem during the Mao era – had never been solved, Zhang said. “Deng could not resist the temptation of power, either,” he said. “He had the final say over almost everything then.”

When Deng became the supreme leader in the 1980s, he had the last word over issues ranging from the appointment of top cadres to the shooting of student protesters in Tiananmen Square, allowing limited scope for challenges from others in the leadership.

And while Deng ordered the political system be overhauled, when he heard of a suggestion to further empower the National People’s Congress, China’s legislature, he told the drafters of his plan to steer clear of Western notions of separation of powers.

While Deng held on to a concentration of power, he also oversaw comparative political tolerance, under which liberals dominated most official academies and think tanks and critical studies of the Cultural Revolution were popular.

But there has always been a red line around Mao as a totem of the party’s power.

When three young people threw eggs at Mao’s portrait in Tiananmen Square in May, 1989, pro-democracy student protesters swiftly handed them to the police, fearing the trio were plainclothes officers trying to frame them and create a pretext for a crackdown. Student leaders later regretted doing so – the trio were jailed for more than 10 years.

After the Tiananmen crackdown, the party moved swiftly to tighten restrictions on public discussions of the Cultural Revolution and other unflattering periods of the Mao era.

Deng’s plans for political reform were sidelined in the years that followed. The party’s decision-making procedures for key policies have remained unchanged and there is little balance to be found outside the echelon of the top few people – let alone from any institutions outside the party.

“The soil of the Cultural Revolution is still fertile now,” Zhang said. “Power is still highly concentrated, sometimes on one man alone. It’s very dangerous.”

Despite this widely held concern, the top leadership has rarely made even the slightest mention of the revolution, let alone criticised it.

It surprised many when former premier Wen Jiabao (溫家寶) brought up the topic while urging political reform four years ago.

“Without the success of political reform ... tragedies like the Cultural Revolution may recur. Every responsible party member should feel the urgency,” Wen told reporters in 2012, recalling the 1981 resolution.

The discussion has grown more delicate since, especially following the remark in 2013 by Xi Jinping (then the new general secretary) that Mao’s three-decade rule “could not be repudiated” by the era of reform started by Deng in the late 1970s – an argument not broached by top leaders in past decades.

“Try to picture, if we fully repudiate Comrade Mao Zedong, can our party stand still? Can socialism stand still? They won’t be able to, and chaos is doomed to follow,” Xi said, adding that attitudes towards Mao were “more a political issue” than a historical one.

“Subversive forces outside and inside China” were always trying to use the history of China to “confuse the hearts and minds”, with the ultimate purpose of overthrowing the communist regime, he said.

Some have wondered whether Xi’s remark, though not directly contradicting the 1981 resolution, signalled the party’s attitude had tilted favourably towards Mao’s political legacies.

He Yiting, vice-president of Party School of the Central Committee, said Xi’s remark was a “further development under the new era” of the resolution.

A resurgence in favourable attitudes towards Mao had stalled the progress of mild political reforms under one party rule, said Andrew Walder, an expert on the Cultural Revolution with Stanford University.

“Mao, above all, was a leader who attacked bureaucratic privilege in the most radical of possible ways, and kept corruption to very modest levels... practically non-existent by current standards in China,” said Walder. “The consequence, of course, is that political liberalisation ‘Chinese style’ has been put on indefinite hold.”

Walder’s concern is sensed within the party, too. Xi’s protective remark regarding the Mao era would cause confusion and a revival of Maoism among cadres, said Wang Haiguang, a former professor with the Party School, the party’s top academy.

“Three decades of reforms were built on the ground that the first thirty years were repudiated. It’s very wrong to say we should inherit Mao’s legacies,” said Wang, who witnessed the party’s efforts to contain Mao’s legacy in the 1980s, when the party encouraged discussion of the revolution.

“It would cause a revival of leftist thoughts like class struggle and cause confusion over political and historical concepts,” said the retired professor who taught party history to cadres.

“[Cadres] would forget that all the reforms are built on the denial of ultra-leftist thoughts ... they would see tragedies in the Mao era as hymns,” said Wang. “There are consequences already, as some cadres are reaffirming the concept of class struggle.”

Wang Weiguang, a ministerial level cadre, is among the most high-profile officials to trumpet the once-sidelined teachings of Mao, including class struggle.

As the director of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, he argued in an article in 2014 that socialism and capitalism remained “in a life-or-death struggle” and that class struggle “would never be quenched” – using terms popular in the revolution.

In 1962, Mao had urged the country to “never forget” class struggle, which was then not the priority of the party. Four years later, he used the same concept to start a decade-long revolution to destroy numerous intellectuals and cadres.

The debate about class struggle has resurged after decades of disproportional studies of the Mao era, under an unwritten rule of “better to go left than right”.

Many documents about the Cultural Revolution are still closed to the public and non-official scholars.

Reading the papers written by Red Guards that are archived in Beijing’s National Library of China, for instance, requires approval from the General Office of the Central Committee, the Central Organisation Department or the Ministry of Public Security, according to Yin Hongbiao, an expert on the revolution formerly with Peking University.

While it remains very hard to get funding for academic studies on the revolution, funds are never short for subjects like industrial achievements under Mao.

The same is true at the Party School, an academy once dominated by reform-minded liberals.

Wang Haiguang, the retired professor, said courses critical of the revolution had been significantly condensed since the 1990s, while courses on Mao’s leadership style had been on the rise.

The trend has become more noticeable in the past four years. Two years ago, around the same time discussions about “class struggle” resurfaced, Yanhuang Chunqiu, an influential and respected magazine catering to the party’s liberal camp, was put under the supervision of an academy under the Ministry of Culture, paving the way for its demise.

Until then the magazine had remained – remarkably – immune to China’s far-reaching censorship system, thanks to the support of many party elders.

Founded in 1991 by Xiao Ke, one of the seven retired generals who wrote to Deng advising against martial law in Beijing before the 1989 crackdown, the magazine has often explored the details left out of official narratives on the Mao era, sometimes challenging those narratives.

It had received open support from many retired senior cadres, including Li Rui, once a secretary of Mao, who later oversaw the appointment of cadres to ministerial level positions. Xi Zhongxun ( 習仲勛 ), President Xi’s father and a former deputy premier, wrote a calligraphic scroll in 2001 to praise the publication.

Yet as the party introduced a new slogan, declaring war on “historical nihilism” – a term referring to challenges to official narratives of history – the magazine found it was no longer an exception.

Its new supervisory body decided in July to sack publisher Du Daozheng, an influential and liberal-minded party elder.

The abrupt change took place only two months after the 50th anniversary of the start of the Cultural Revolution, and coincided with bombshell articles run by the magazine in which influential party intellectuals called for greater reflection on the revolution.

Its original authors and editors, furious at the decision, decided to boycott the academy. But they were soon replaced by Maoist scholars who slammed the magazine as “anti-Mao” and “anti-communist”.

“What happened to Yanhuang Chunqiu is an important signal,” said Yin Hongbiao.

“After the example was set, I’m afraid other publications would not dare to run articles that expose or explore negative facts in history.”

As early as 2010, when Xi was the president of the Party School, he had started making speeches on the necessity of upholding the “correct” narrative of history, linking the issue to the political safety of the party. He continued to do so after rising to the top of the party in 2012.

“Overthrowing a country usually starts with destroying its history,” Xi said in the 2013 speech, calling for a “correct” attitude towards the Mao era. He went on to warn that fully repudiating Joseph Stalin was one of the key reasons the Soviet Union collapsed.

“They don’t necessarily want the Cultural Revolution to recur, but they definitely [see talking about it] as a liability,” said Ye Yonglie, a writer who has close ties with the authorities and has published multiple books about the revolution on the mainland.

The mistakes of Mao were seen by the party as being as fatal as the mistakes of Stalin, Ye said. “They don’t deny the mistakes of Mao, but would [rather] not talk too much about it.”

Later in 2013, Xi again brought up the collapse of the Soviet Union. He urged the propaganda authorities to give no space to rumours that “distorted the history of the party and the country” and to proactively denounce those “rumours”.

The meeting was held on the 22nd anniversary of the 1991 coup in the Soviet Union, when hardliners of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union tried to seize power from the reform-minded president, Mikhail Gorbachev, without success. Gorbachev resigned four months later, dismantling the massive empire.

Xi did more than just talk about efforts to distort history. Top-level inspectors, key to Xi’s anti-graft campaign, slammed the party’s top academy in February as being “not proactive enough to [speak] against historical nihilism”.

Despite the party’s trumpeting of Mao, it remained highly selective when choosing which legacies to continue, said Ding Xueliang, a professor of sociology with the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

“The party today doesn’t treat any of Mao’s legacies seriously, except for the ones they really need,” Ding said. Absolute control over the military, a system for coercion, and effective management of party members were among the few things the party was willing to learn from Mao, he said.

It was unlikely that today’s party would allow a bottom-up mass movement like the Cultural Revolution to cleanse its own leaders, Ding said.

“For them, the most scary part of the Cultural Revolution was that incumbent party leaders were targeted. Mao aimed to oust the majority of cadres. The leaders now would never do that.”

While current leaders tiptoe over the legacies of Mao, it seems to many that the controversial late leader is the only choice for the party to rally the country behind.

“If you want to harken back to a grand national tradition, there is really no one else to stand in as a founder,” said Andrew Walder with Stanford University.

“The current leadership’s conception of the party’s good traditions actually are more accurately associated with a different leader, Liu Shaoqi ( 劉少奇 ), whose primary contributions were to strengthen the party’s discipline and ensure effective governance,” said Walder.

Liu, who never sought to confront Mao’s authority, had overseen the daily operation of the state for about half a decade before his fall in the revolution. Though Liu was equally iron-handed in political purges, he did try to rid the party of fanaticism during the Great Famine, and to contain anarchy at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, both to the discomfort of Mao.

Other party elders, like Zhou Enlai (周恩來) and Deng, are often seen as merely implementing Mao’s wishes, even though Deng led the country out of the debris following Mao’s death.

But many scholars, including Walder, believe Xi’s campaign to restore Mao’s reputation, though partly tactical, is also sincere.

“He does harken back to the Maoism of the pre-Cultural Revolution era,” said Walder. “The idea of pure commitment to party ideals and selfless serving of the people is something that surely inspired him and his generation then.”

Xi, who has repeatedly emphasised that “revolutionary ideals are higher than the sky”, saw his deep faith in Mao’s doctrines unshaken despite the sufferings of himself and his father during the revolution.

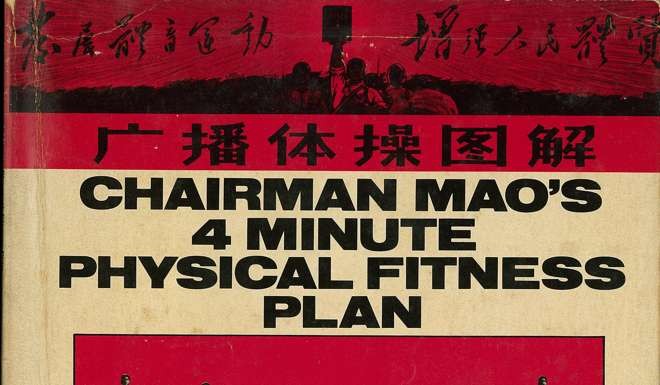

In an interview in 2000, Xi, then governor of Fujian ( 福建 ) province, said he read Quotations from Chairman Mao every night during the revolution, a period when his father was labelled an “anti-party element”. Around that time, Xi himself was besieged by a mob and later sent to the countryside for hard labour.

Historians argue Xi’s generation, born in the 1950s after the party fully asserted ideological controls, grew up without formal education through the Cultural Revolution and are therefore heavily influenced by communist traditions.

But generational attitudes, much like the portrait in Tiananmen Square, can change, and the next crop of leaders may have lost their natural affection for Mao.

“[Xi’s generation] were the most profoundly educated with communist traditions, but they’ll be the last generation,” said Liu Xiaomeng, a historian with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the central government’s top think tank.

The next generation of Chinese leaders, born after the 1960s, mostly received college education after the revolution ended and matured through the 1980s, when the party embraced unprecedented political tolerance and openness.

Should Xi, like previous leaders of the past three decades, step down after two five-year terms, the next generation of cadres will rule China following the 20th party congress in 2022.

“They grew up in a period of much greater freedom and openness to the outside world – they are also much better educated,” said Walder with Stanford University. “I would be surprised if their world view and attitudes were not more liberal.”