What’s driving Malaysian support for Islamic penal code?

Critics say introduction of a strict sharia punishment code known as hudud could dissuade investment, strain social harmony, ruin Malaysia’s reputation and encourage extremism. So why would PM Najib Razak view it as a vote-winner?

As Malaysia considers the introduction of a strict sharia punishment code known as hudud, minorities have been left to consider their place in a country once lauded for diversity and moderation – and to ponder the wisdom of experts who warn creeping Islamisation could breed extremism.

Scenes of the tens of thousands who gathered in Kuala Lumpur in February to show their support for hudud are fresh in the minds of lawmakers who are being urged to debate the implementation of aspects of the code before the current parliamentary session ends on April 6.

Also at the forefront of their minds – and not least that of embattled Prime Minister Najib Razak – is the looming general election widely expected to be held this year. For the first time since the country’s independence from Britain in the 1950s, there appears a real possibility that the ruling coalition known as the Barisan Nasional (or National Front) could lose power (it clung on at the last election, in 2013, despite losing the popular vote).

Given the tightness of the margins, an issue that for decades has been too divisive for lawmakers to entertain has emerged as an unlikely kingmaker.

Under Malaysia’s parallel legal system, secular federal laws operate in tandem with sharia courts that have jurisdiction only over Muslims and only in some aspects of (mostly civil) law that are not covered by the federal law. However, at present, those sharia courts are restricted from implementing the harshest punishments, for those crimes said to violate God’s boundaries (or hudud). In its purest, strictest interpretation, the hudud code prescribes amputations, stonings and even crucifixion for certain offences.

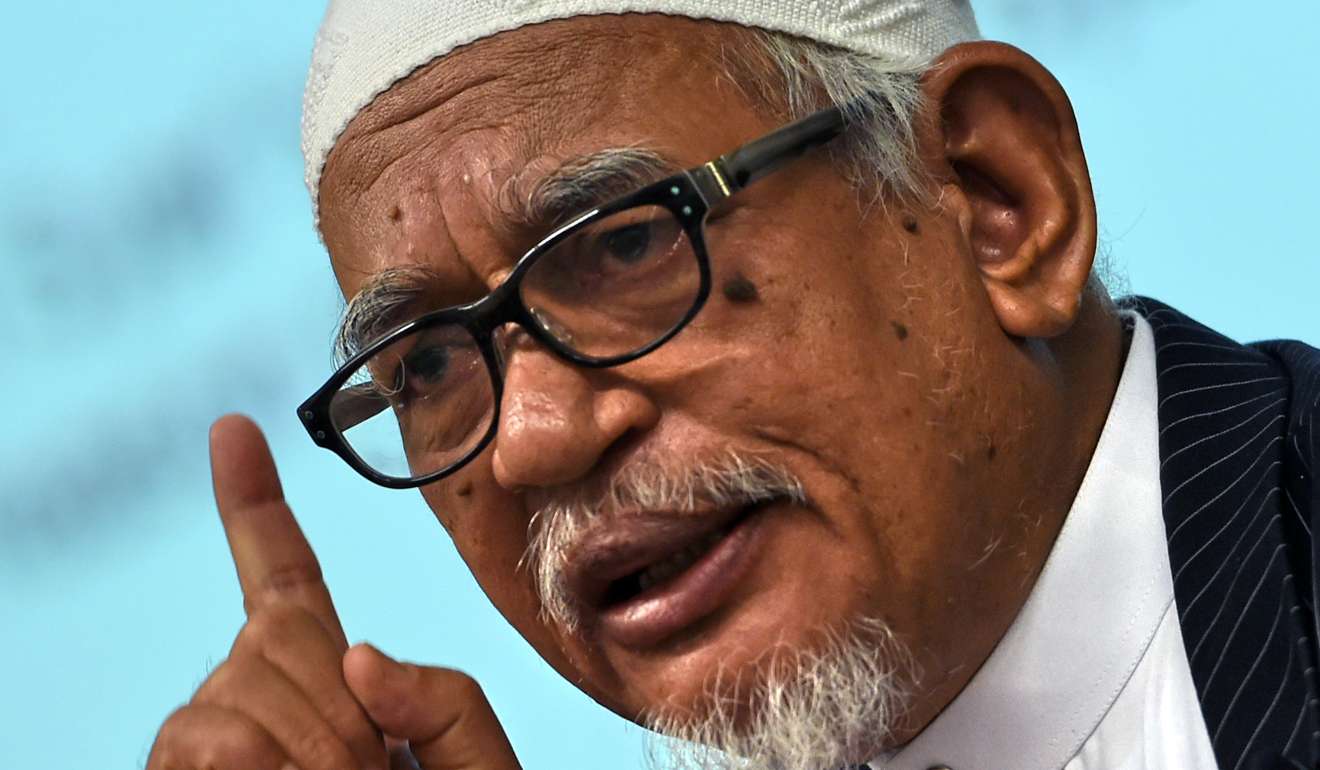

But there is sizeable support for implementing hudud – witnessed most recently at the rally in the capital to support a private member’s bill by Abdul Hadi Awang, the leader of the country’s influential Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS). His bill’s scope is limited: it seeks only to ease some of the restrictions imposed on the sharia courts and – the more archaic punishments, such as crucifixion, would remain off limits.

Still, the limited scope of the bill has done little to dispel the doubts of those who fear that in playing to the rural Muslim voters the politicians are embarking on a slippery slope.

Abdul Hadi’s bill alarms many of the country’s non-Malay minorities who see such efforts as part of a creeping Islamisation of the multi-ethnic country and claim it would dissuade investors and strain social harmony. About 23 per cent of Malaysians are ethnic Chinese and seven per cent Indian. The direst warnings see it as contributing to a climate of religious conservatism that could leave the country a fertile ground for the Islamic State terrorist group.

That leaves all eyes on Najib, who leads the United Malays National Organisation, the main party in the ruling coalition, and who is in need of a popularity boost.

On first glance, Najib appears an unlikely supporter of the bill. The ruling coalition has often exploited the issue to drive a wedge between opposition parties such as the PAS – the biggest Islamist party – and the secular Democratic Action Party. And it has been successful in doing so: in 2015, disagreement over hudud caused the disbandment of the opposition coalition, the People’s Alliance, just two years after it lost the 2013 elections (despite winning the popular vote).

But Najib has plenty of reasons to rethink his position, not least among them the loss of support he has felt since being linked to a scandal at the state fund 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), where investigators reportedly traced some US$700 million wired into his bank accounts. Both the fund and Najib deny wrongdoing, but the scandal has encouraged many Malaysians, particularly urbanites and non-Muslims, to turn away from his ruling coalition.

His response has been to court the PAS on the basis of Malay-Muslim unity with his own party. While he has so far stopped short of endorsing the bill, opponents fear that will be the ultimate quid pro quo the PAS demands.

Najib’s ploy, at least for now, appears to be working. The government’s move in May last year to allow Abdul Hadi to table the bill – the first private member’s bill to gain a hearing since 1988 – set the media agenda for two by-elections the following month, both of which were won by Najib’s ruling coalition with increased margins.

Given such developments, it’s perhaps unsurprising that the bill’s supporters are optimistic.

Yet Najib is wielding a double-edged sword. Some of his party’s partners in the ruling coalition, such as the Malaysian Chinese Association, have threatened to vote against the bill, while ministers and business groups warn it could drive away investors already spooked by the 1MDB scandal.

In June, the International Trade and Industry Minister Ong Ka Chuan warned passing the bill would cause investors to reconsider their place in Malaysia. “Our trade will be affected and this will be detrimental to our economic fundamentals,” he said.

Even more striking are the warnings that calls for hudud are part of a creeping Islamisation that will breed extremism. In testimony to the US congress on assessing the threat terrorist group Islamic State posed to Southeast Asia, Joseph Liow of the Brookings Institution think tank said “the climate of religious conservatism and intolerance [in Malaysia] has created fertile conditions for [Islamic State’s] ideology to gain popularity”.

While stressing that supporters of hudud were generally non-violent, Badrul Hisham Ismail, of Iman Research, said they nevertheless shared a strand of thought with the terrorist group. “It’s that perception that by going back to so-called pure Islam, you can solve problems – crime, corruption, socio-economic problems,” Badrul said.

The PAS brushes such warnings aside. “Investors will be assured if a country practices a system and laws that are just and transparent with zero corruption,” said the party’s information chief Nasrudin Hassan. “That is what Islam wants to build, through sharia law.”

DECADES OF DIVISION

The debate must be seen against a backdrop of decades of division on the issue, which reaches to the heart of Malaysia’s parallel legal system.

While Malaysia’s secular federal laws are based on the common law legal system inherited as a result of the country’s colonisation by Britain in the early 19th century, the constitution gives individual states the authority to legislate for offences and punishment of Muslims, except for matters already covered by federal law. This parallel sharia system covers matters like family law, religious observances and offences not covered by federal law such as adultery, false accusation of adultery, intoxication and heresy. Offences like theft, robbery, rape, murder, incest and unnatural sex are dealt with by the Federal Penal Code and hence off-limits for the states.

The constitution also limits sharia courts in the penalties they can impose. The Sharia Courts (Criminal Jurisdiction) Act 1965 imposes limits of a maximum of three years jail, fines of up to RM5,000 (HK$8,700) and whippings of up to six lashes.

It is these limits that the latest bill seeks to change – it envisages limits of a maximum of 30 years’ imprisonment, fines of up to RM100,000 and 100 lashes.

In 1993 and 2002, the state legislatures of Kelantan and Terengganu approved the use of hudud punishments such as amputation, stoning and crucifixion for offences such as theft, robbery, fornication, sodomy, false accusation of fornication, drinking and heresy.

But these punishments were unenforceable as they contravened the constitution’s limits on sharia.

While the hudud bill would not change this, critics fear it will be the thin end of the wedge – encouraging other states to follow suit and giving fuel to groups already calling for a wider application of hudud. “This will open the floodgates,” said Wong Chin Huat from the Penang Institute think tank.

Indeed, some groups are already calling for a wider application of hudud. While the PAS maintains that hudud should not be imposed on non-Muslims, groups like the influential Malaysian Muslim Solidarity (ISMA) movement have called for its universal application. The ISMA president, Abdullah Zaik, said: “We believe an Islamic system can be accepted and will assure everyone that an Islamic system will protect their interests.”

The appetite for hudud had been building long before the rally in Kuala Lumpur. In a 2014 survey by pollsters Merdeka Centre, 71 per cent of Malay-Muslims supported its introduction (though approval from non-Malays was below 30 per cent).

That has led some to claim that increasing distrust in the government, rising crime and costs of living are fuelling an urge among Muslims to look to the divine for solutions. Others blame the PAS for indoctrinating Malay Muslims to believe that rejecting hudud is a rejection of Islam. “Today, even non-devout Muslims will say they want hudud, out of fear of apostasy,” said Wan Ji Wan Hussin, a Muslim preacher who has left the party.

Yet the Merdeka Centre poll also showed only 30 per cent of Malays thought the nation was ready for it.

This hesitance was echoed by Che Ibrahim Mohamed, a sharia lawyer and former member of the Kelantan technical committee on hudud. “[Hudud] shouldn’t be the priority right now,” he said.

“We need to ensure the needs of the people are met first. When their educational and welfare needs are met, then we can talk about the law. It’s like building a house, and hudud is the fence. We need to ensure the house is functional first before safeguarding it with a fence.”

ISMA’s Abdullah was not impressed by such arguments. “If crimes can be stopped solely by way of education and understanding, we would choose that path too. But where [society has been] unable to curb crime, the laws need to be in place. We do not need to wait for society to understand before implementing those laws.”

A LOSING BATTLE

With such firm views on either side of the debate it may seem hard to envisage a common ground being reached any time soon. Yet it might be that the two sides already have something in common – a misunderstanding about sharia.

Dzulkefly Ahmad, a former PAS leader who formed a new party, Amanah, said that the debate had “reduced everything to the punitive.... but sharia is not about that at all”.

He noted that the Arabic word ‘hukm’ was used in the Koran to mean arbitration, judgment, authority and Allah’s will, but “the Malay word ‘hukum’, as used in Malay-Muslim society, had come to mean punishment and the penal code”. Consequently, “we’re in a losing battle if we want to disentangle [the debate]”.

Not only has this reductionism oversimplified the matter, it has made hudud appear a panacea in the Malay-Muslim psyche – a cure for crime, a symbol of identity, a cause for the politicians, a vote winner for a down at luck prime minister. Whether or not the present bill passes – and whether or not it leads to the slippery slope feared by some, Dzulkefly is keen to shatter such illusions. “There has been empirical research done on countries that have implemented hudud and there is actually an inverse correlation between hudud and quality of life and justice. Sudan, Pakistan, Nigeria – look at their level of integrity, income disparity, crime, violence. It is not that simplistic,” he said.

“A lot of factors contribute to crime. But in this simplistic mind, if you get hudud implemented, all problems of man will be solved. If that was the case, the Prophet would’ve pronounced hudud from day one.” ■