Umbrellas now and then: 20 years since Hong Kong handover, have things really changed?

The sun may have set on Britain’s last major colony two decades ago, but today it is largely business as usual in the Chinese SAR of Hong Kong

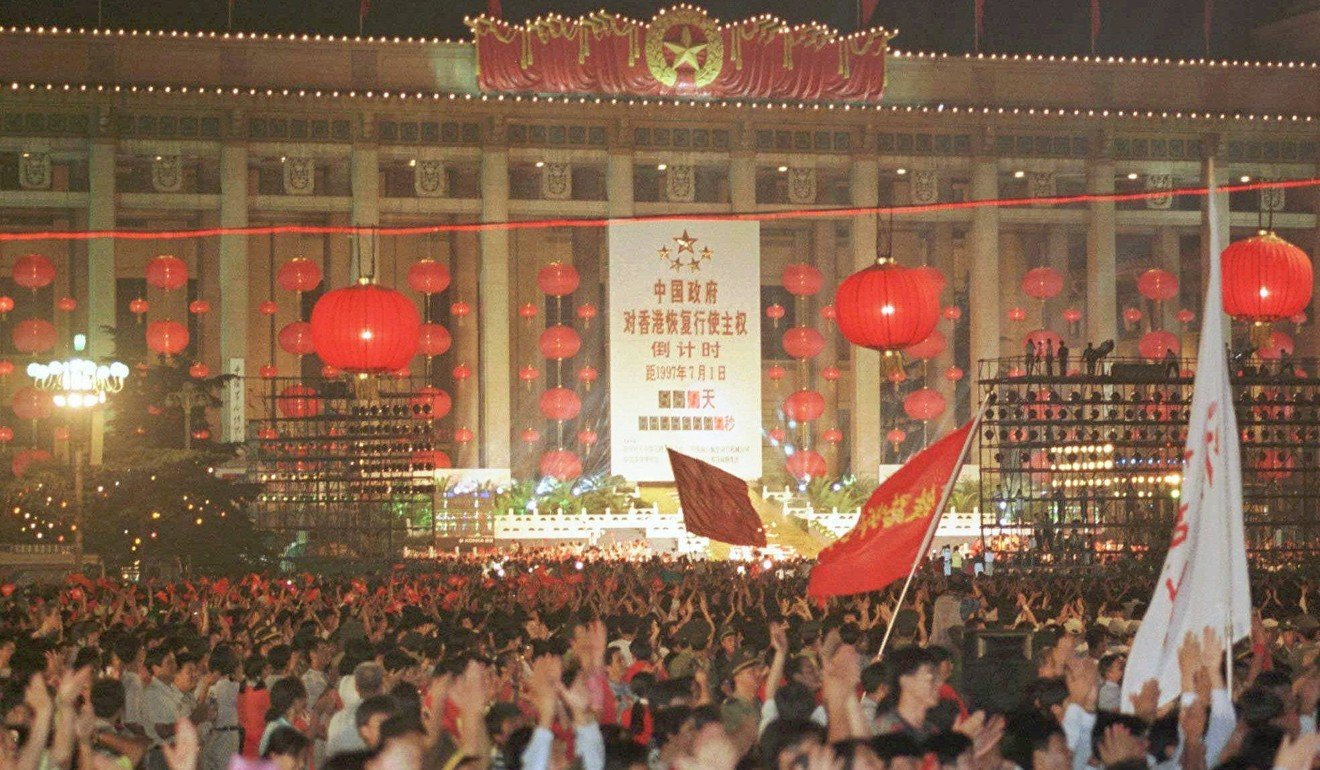

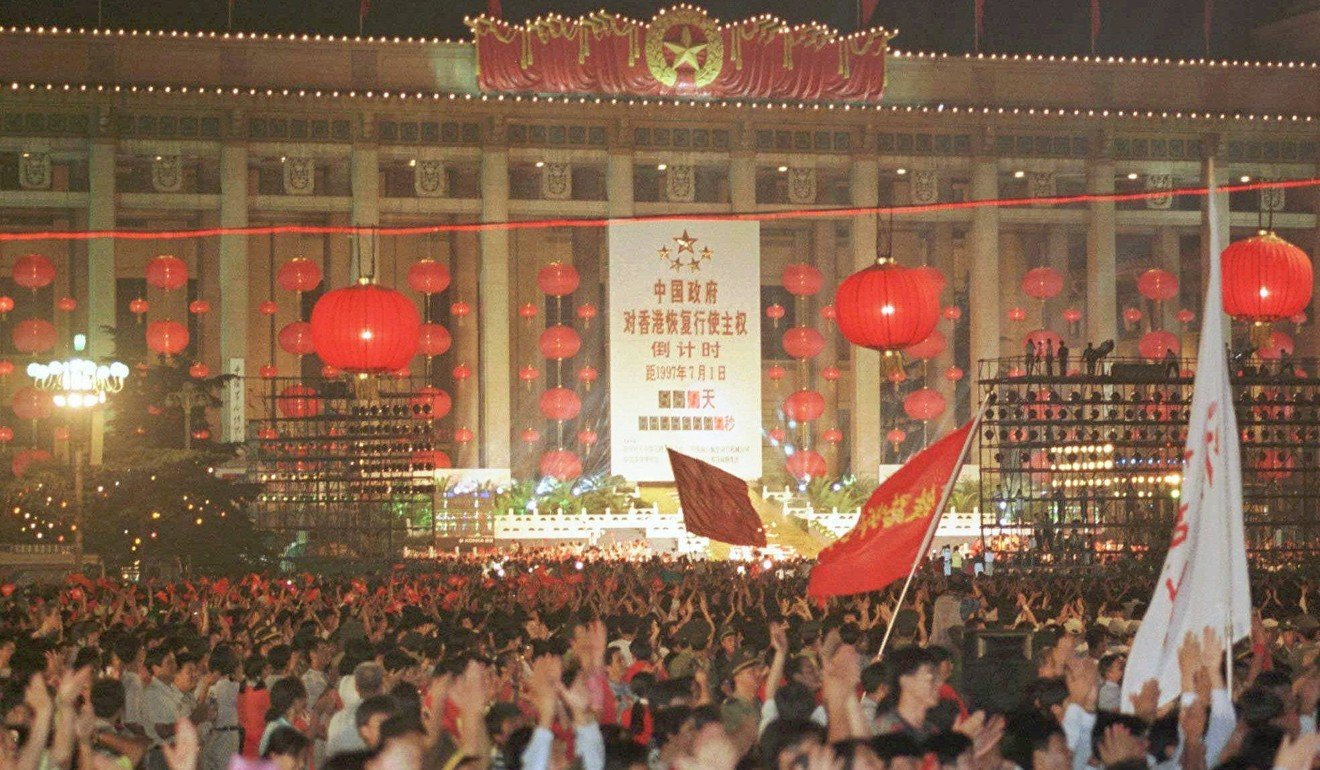

For a moment in history preceded by epic anticipation and morbid speculation – by a giant clock display in Tiananmen Square counting down the days, hours and minutes to Hong Kong’s return and Fortune magazine’s The Death of Hong Kong cover story two years earlier – the night of June 30, 1997 could not have been more uneventful. Within days of the People’s Liberation Army soldiers moving into barracks vacated by the British, there were complaints from nearby shopkeepers that business had plummeted. The protests by the Democratic Party on the night of the handover did not end, as many had predicted, in the arrest of its leader, Martin Lee Chu-ming. Even Hong Kong Human Rights Monitor found little to complain about on that night of civilised protests and civilised policing: “In general, the police were very well organised and sensitive. The main blemish was … the police set up a sound system and played Beethoven’s 5th from it. This … is an unacceptable and unlawful curtailment of [demonstrators’] right to freedom of expression.”

I had moved from New York to Hong Kong the previous year with Time magazine, so seduced by the prospect that I accepted the job as the magazine’s regional business writer without even asking on what terms. My first assignment on June 30 was interviewing Jan Morris, the author of the finest book on Hong Kong in the run-up to 1997 because she sought to capture its energy and resilience in a series of snapshots and steered clear of apocalyptic predictions. When we met, Morris likened Governor Chris Patten, about to take a break in France to write a book, to the great orator Cicero biding his time in exile from Rome a couple of millennia earlier. It seemed only a matter of months before the Conservative Party, then as now short of leaders with Lord Patten’s charisma, would summon him to greater things. I would see Patten twice that day, first as his car drove by in the morning to loud cheers from the crowds and then at the departure of the Royal Yacht Britannia.

On the night of June 30 and in the days after, the city witnessed downpours like something out of a myth. It rained non-stop through the handover ceremonies. The soldiers were drenched, the grandees attending had to have umbrellas hoisted above them. As Prince Charles mingled with guests invited to the departure of the Britannia a couple of hours later, he made light of it: “I have never given a speech before completely under water.” Conscious the occasion was also a public-private farewell for Patten and his family, Prince Charles kept a low profile.

Even the relentless rain could not hide that Patten and his daughters were weeping as the Britannia pulled away from the docks on its last journey home before it was decommissioned. Two curious coincidences marked the event: The handover that night of this gleaming jewel-box of a city was 100 years since Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee on June 22, 1897. And, the first royal passengers on the Britannia in 1954 had been Prince Charles, then 5, and his sister Anne.

Inevitably, given the ambivalence and anxiety about Communist China taking over this outpost of entrepreneurial energy, many saw the deluge as an omen. The genial security guard at my building remarked: “The heavens are crying for us.”

Shortly before the signing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration in 1984, the colonial government set up an ”assessment office” to survey how the population felt about it, headed by a distinguished Oxford academic and the respected Hong Kong judge, Simon Li. As ever with colonial Hong Kong, whose bizarre functional constituencies in the legislature complicate decision-making to this day, professional associations and unions were among those whose opinions were recorded. There ought to have been a referendum, opined the Cotton Bleaching and Dyeing Free Workers’ Union. The report noted “neither positive enthusiasm nor passive acquiescence” but a bedrock of “realism”. The people of Hong Kong had not been consulted, but remained instinctively businesslike; those who could were hedging their bets, noted Morris.

In the mid-1990s, Li Ruihuan, a liberal opponent of former president Jiang Zemin who stepped down from China’s Standing Committee in 2002, said of Beijing’s relationship with Hong Kong: “If you don’t understand something, you are unaware of what makes it valuable, and it will be difficult to keep it intact.” He likened the world’s most futuristic metropolis to an antique teapot that shouldn’t be scraped too hard. It was a curious analogy, except in relation to the city’s common law system. The principal challenge for China in administering Hong Kong was always going to be understanding the fierce independence of the judiciary and, even more counter-intuitively, allowing elections of the city’s chief executive and legislature in which it could not control the outcome.

For a Communist dictatorship, both were utterly alien notions. By contrast, Hong Kong’s oligopolies in real estate, ports and retailing and its currency peg to the US dollar were not difficult for Beijing to relate to since China follows a state-led capitalism that even disallows unions while its central bank manages a tight trading band with the US dollar. The hardest leaps of faith for Beijing was the idea that allowing greater democracy would boost the local government’s legitimacy and that the judiciary is intended to be a restraint on the executive in a common law system. The real divide was that Hong Kong might physically be part of China, but metaphysically was from a different planet as a city with the rule of law and a mostly free press.

And so it proved. Just a week or two after I returned to Hong Kong in January 1999 as a correspondent for the Financial Times, a thunderstorm of a constitutional story broke over the city. On January 29, 1999, the Court of Final Appeal (CFA) ruled that mainland children with a Hong Kong permanent resident as a parent had the right to live in the city. Reuniting families underpins immigration decisions in many Western countries, but in a ruling boldly and beautifully written, the CFA judges used the case as a Rosetta Stone to expound on how an autonomous court, navigating between two radically different judicial languages, would work. In the case of a conflict with mainland law, the judges asserted that Hong Kong’s laws would prevail. I was making a transition from a magazine’s weekly deadlines to daily news reporting. This story brought on something akin to a panic attack. I happened to call the University of Hong Kong’s law school that evening. By a stroke of luck, I was given the home number of Yash Ghai, a Kenyan-born academic who was the world’s leading expert on the constitutional affairs of newly independent developing countries.

This was a legal battle that, like one of those television soap operas, would run and run. Instead of glamorous LA Law lawyers on Star TV in the 1990s, however, Hong Kong was treated to multiple press conferences where the officials of the Tung Chee-hwa administration won the case in the court of public opinion, a prelude to asking Beijing for its interpretation of this radical judgement. The Hong Kong government unveiled estimates implausibly suggesting that as many as 1.67 million mainland people had the right of abode because of the liberal ruling. Perhaps the anger and prejudices of Hong Kong’s public against mainland Chinese in recent years would have happened anyway given news stories of them snapping up apartments, accessing local schools for their children and conspicuously bidding high at auctions for art and antique vases, but that campaign could not have helped.

Predictably, Beijing overruled the judgement. An article in the Melbourne University Law Review observed, “As subsequent events were to demonstrate, the Standing Committee’s power to issue unilateral interpretations of the Basic Law proved to be the crucial breach in the ‘firewall’ sought to be erected around Hong Kong’s judicial autonomy by the CFA.”

In November last year, in the “interpretation” handed down on the ousting of pro-independence lawmakers from the Legislative Council (LegCo), Beijing pre-empted Hong Kong courts from even making a decision.

Did the CFA overstep? As Ghai would argue, the court was standing up for the “semi-sovereignty” promised by the Basic Law. It is not a subsidiary court to the National People’s Congress. In an article, Ghai quoted the late Deng Xiaoping ( 鄧小平 ) arguing in 1984 that the autonomy accorded Hong Kong was unprecedented – and indeed it is. In May, an Australian lawyer helped me with a will domiciled in Hong Kong covering my bank accounts in the city and in London, a sign of faith in the day-to-day functioning of the legal system I would have thought silly when I first moved here in 1996.

CHANGED?

About 10 days into the umbrella movement in October 2014, a banker carrying a golf club for some reason decided to take a short cut back to his office through the protests in Admiralty. Immediately, students on mini-bicycles rushed over and implored him not to bring a “weapon” into the area. Small stools and makeshift ladders were used to help people get over the three-foot high barriers on the highway. “We don’t want anyone getting hurt,” a teenager said to me.

Almost anyone from Hong Kong travelling, say, to New York or New Delhi is often asked: Has Hong Kong changed? It has not changed enough – even if it is a much kinder, gentler place at street level than I remember in the 1990s. From bureaucrats who devise threadbare social support systems with a stingy colonial book-keeping mindset to signalling Beijing’s choice for the city’s chief executive through choreographed handshakes or telephone calls, Hong Kong seems much as before. A city with a per capita income higher than Britain’s still does too little to help almost a million people who live below the poverty line. It is hard not to be moved by the recurring sight of elderly women pulling carts of flattened cardboard boxes three times their weight as they heave their way past designer stores.

Yet, the government underestimates its fiscal surplus year after year; fiscal reserves are expected to hit HK$952 billion by next March. The outgoing administration may have found more parcels of land for housing than it is given credit for, but until the clans in the New Territories are taken on, housing will remain out of reach for many of the city’s young middle class. I was recently part of a surreal discussion with a Hong Kong friend who is a PR professional married to an engineer. She is unable to buy even a tiny flat and we discussed whether she should arbitrage her Macau residency (she has a parent from Macau) to buy more cheaply there instead.

Every incoming chief executive is first denied the political leverage that would flow from being elected by universal suffrage and then hamstrung by vested interests legitimised by functional constituencies for professions ranging from finance to agriculture and fisheries: Lilliputian leaders are tied down by many other Lilliputians. Beijing has typically anointed as its chief executive candidate either senior civil servants or, as in Communist China, princelings such as Tung and Henry Tang Ying-yen who inherited their wealth and position. My last “political” story for the Financial Times in March 2013 was the sale by Henry Tang at a Christie’s auction of part of his vast collection of exceptional Burgundy wines. In no other plutocracy, other than Trump’s America perhaps, would a politician, whose election campaign had been torpedoed by the discovery of an enormous illegally built wine cellar, preface a wine auction with these words: “I have assembled a collection that many would die for, but alas, I am mortal.”

As the 20th anniversary of the handover approaches, what used to be the old government offices on Lower Albert Road are under scaffolding. As I walk by daily, it is hard not to be reminded of C.H. Tung’s mantra repeated in almost every interview: “One country, two systems is working well. Hong Kong is moving forward.” And, of Donald Tsang Yam-kuen’s reply as financial secretary when asked by a reporter why he wore bow ties. They were less expensive than ties – if one was comparing brands like Hermes – the police officer’s son said revealingly two decades before he was handed a harsh prison sentence for not disclosing a potential conflict of interest. As chief executive, Tsang transferred the government’s office to the corporate-Stalinist skyscrapers in Admiralty, now defined in our mind’s eye as the backdrop for the protests of 2012 and 2014.

The security guards at what is today a mostly empty building are as professional as the ones I remember two decades ago. Despite the construction work, the place is spotless. Alongside the banners decorated with the slogan of the 20th anniversary – “Together Progress Opportunity” – flutters a more modest one, calling for applications from blue-collar workers to upgrade their skills. The giant blue gauze bandage that hangs over the compact and easily accessible office complex thus seems an allegory of a city where the ordinary immigration official, fireman and bank clerk remains supremely efficient, courteous and among the most conscientious anywhere, yet Hong Kong is encumbered with a political leadership bruised and battered even before a new term begins. ■