Inverted flags, illegal migrants: how Malaysia-Indonesia ties took a turn for the worse

Malaysia last month rounded up thousands of undocumented workers, adding fresh animus to a long-running dispute

With promises of higher wages and easy work, an agent lured Abu Bakar, 36, and his wife from their village on the island of Madura, off the coast of East Java. The agent delivered them, without a work visa, to a fruit processing factory just minutes from Kuala Lumpur, the Malaysian capital, and took their passports. That was four years ago.

After paying for rent, food and cigarettes – Bakar’s only indulgence – he and his wife, Puniyati, 33, who washes clothes for a few hours a day, are left with about 500 ringgit (HK$915) each month. That is roughly what Bakar would have earned on Madura. Most of what is left he sends home to his son. But because he and his wife have no proof they are entitled to be in Malaysia, they are easy pickings for thugs and even uniformed police.

Bakar says he has been detained and beaten for money, which he pays to avoid further trouble. The abuse has taken a toll. Bakar says all he and his wife want is to go home.

“I have nothing left here. Only surrender,” Bakar says. “I want to go home but I can’t afford it.”

The flow of migrant workers has become a sore point in relations, and that wound risks reopening after Malaysia rounded up thousands of undocumented workers last month. Activists claim a new round of deportations is imminent.

“It will be any time,” says Sumitha Kishna, the co-founder of the Migration Working Group and an industrial lawyer. “There is no question they [the detained undocumented workers] will be released.”

Activists claim Malaysia has rounded up some 5,000 undocumented workers, mostly from Indonesia but also from Myanmar, Bangladesh, and Nepal. The tally will almost certainly grow. Malaysia has reportedly arrested some 146,000 migrant workers since 2014.

Even migrants like Bakar, who want to go home, avoid the police because capture often means paying

a fine equivalent to three months’ wages and then languishing for weeks or months in detention as their home countries haggle over their repatriation.

Repeated phones calls and text messages seeking comment from officials, including Dr Iqbal Lalu, director for protection of Indonesian Nationals at Indonesia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs were unsuccessful.

Officials at Indonesia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs declined to comment on Malaysia’s arrests or arrangements for the deportation of those detained.

Dr Iqbal Lalu, director of the protection of Indonesian nationals, did not answer repeated phone calls and text messages seeking comment.

The recent Malaysian round-up followed a seven-month pause during which officials offered temporary amnesty while employers went through the proper channels to secure work permits. The process was expensive, time-consuming and risky, and only 22,500 undocumented Indonesians took up the offer, according to data collected by Jakarta-based Migrant Care from Malaysian immigration authorities.

Previous amnesties were similarly underwhelming, in part because those failing to qualify were deported. In one amnesty in 2011, 662,000 applied but more than half failed to meet the criteria and were sent home.

Heavy-handed tactics play well with voters who are hostile to illegal migrants, who accuse them of stealing jobs, driving down wages and committing crimes.

Kishna insists those accusations are unfounded, with only 2 per cent of crimes in Malaysia committed by migrant workers.

Kishna notes that hiring illegal workers makes for good business. Despite its many purges, Malaysia remains hooked on illegal foreign labour. Local media estimate they account for at least 30 per cent of workers.

It is hard to know how many of those are Indonesian. But Migrant Care has assessed Malaysia’s construction activities and its areas under cultivation for plantation, and accounted for the historical proportions of illegal workers by nationality. It has concluded at least 1.8 million Indonesians are likely working in Malaysia without a permit – more than double those working in the country legally.

“There’s a double standard,” says Anis Hidaya, executive director of Migrant Care. “They have the law but employers like hiring undocumented workers because they don’t have to pay taxes or benefits.”

The issue of illegal migrant workers has long been a sticking point between the two countries. Relations soured dramatically in 2002 when Malaysia deported 400,000 Indonesians to the tiny island of Nunukan off the east coast of Kalimantan, creating a humanitarian disaster. Reports described thousands being forced to sleep in the open and rampant disease as patients overwhelmed the 10-bed clinic.

To be sure, despite the amnesty that ended in July, a trickle of deportations persisted throughout the year.

Malaysia has shipped out 1,000 or so Indonesians from its easternmost province of Sabah so far this year, an official at Indonesia’s consulate there said, asking not to be identified. Those deported had been detained before the amnesty went into effect in February, the official said.

There is no public empathy for migrant workers. They are seen to be taking jobs and destabilising wages

In Indonesia, nationalists have bristled over the way their countrymen are compelled to do their neighbour’s dirty work. President Joko Widodo is determined to end the practice of sending housekeepers, construction workers and plantation help, complaining it erodes the “country’s dignity”.

In May 2015, the government banned the placement of domestic workers in 21 Middle East countries after Saudi Arabia executed two Indonesian women who were convicted of murder.

More bans, though, seem unlikely. In remote parts of the country there is no shortage of Indonesians willing to skirt the law for the chance of a well-paid job away from the grind of village life.

Some travel on visas intended for religious pilgrimage for the chance to earn more and send money home. This makes those migrants harder to reach should things go wrong with their employers.

By definition it is impossible to know how many Indonesians are working abroad illegally. Government statistics suggest it may be as many as 4.5 million. The money they send home adds up.

And then there are the remittances. Migrant Care estimates Indonesians sent home nearly US$9 billion last year. If they were counted as exports, Indonesia’s foreign workers would be the country’s third-most-lucrative sector.

Yet Indonesia has an awful track record when it comes to caring for foreign workers on its own soil, as well as its own workers abroad. Indonesia has yet to ratify the 2011 International Labour Organisation convention for domestic workers.

Activists complain Indonesian diplomats are slow to protect their nationals overseas, especially if they are working illegally.

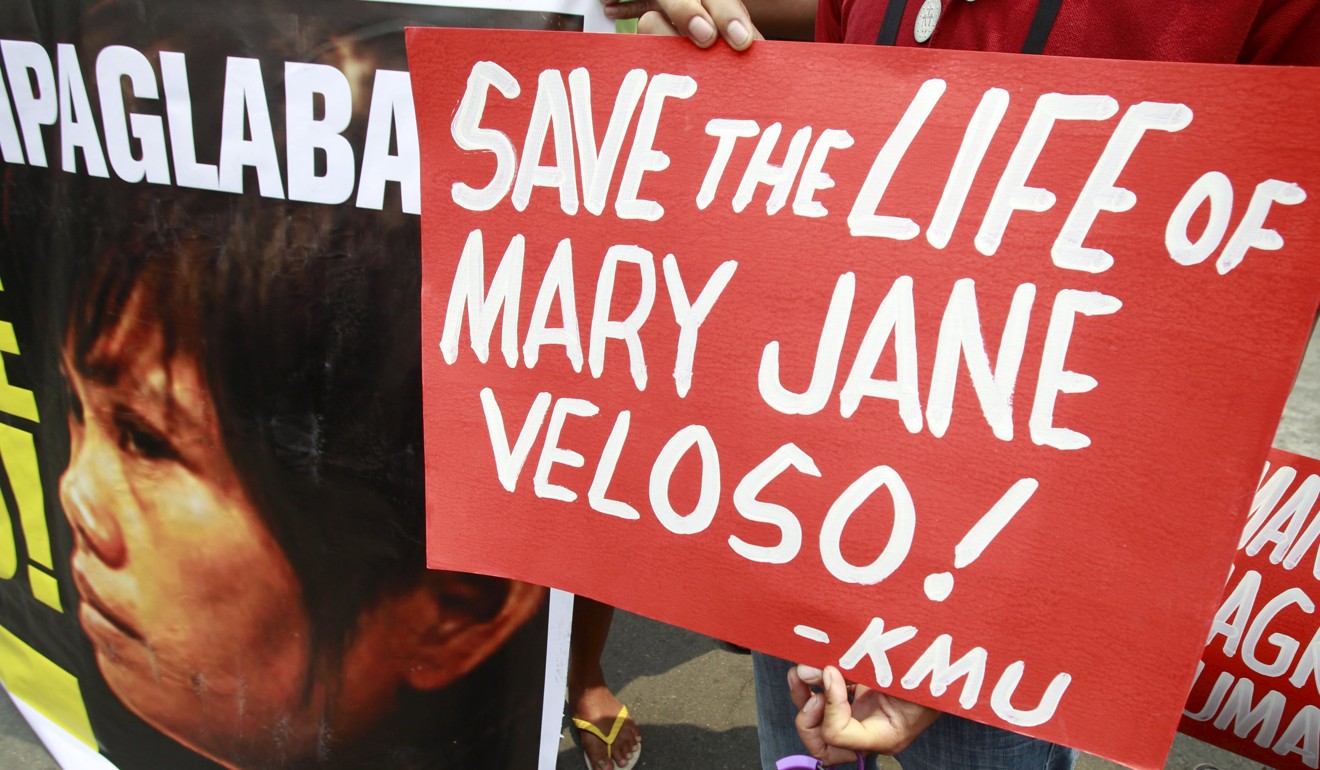

In 2010, an Indonesian court sentenced to death Mary Jane Veloso, a Filipina maid, for smuggling heroin into the country. Activists claim she was the victim of human trafficking.

“There is no public empathy for migrant workers,” Kishna says. “They are seen to be taking jobs and destabilising wages. They aren’t recognised for the contributions they make.” ■