Why are ethnic Chinese still being denied land in Indonesia?

Twenty years since the fall of Suharto, a sultanate clings to colonial era notions and a ban on ‘non natives’ owning land – raising questions as to whether the country has laid to rest its dark past of racial and religious tensions

When bicycle seller Willie Sebastian was offered a plot of land by the Indonesian government, little could he have known it was the start of a long and humiliating process that would eventually leave him not only empty-handed but feeling like a second-class citizen in the country of his birth.

As part of a drive to beautify the area around the Prambanan temple complex in Yogyakarta – a site that has welcomed such foreign dignitaries as Barack Obama – the state government had promised Sebastian an 80-metre square plot in return for him agreeing to relocate his store. Ever the good citizen – and optimistic about his prospects in the new area – Sebastian agreed and headed for the land agency in Sleman regency. But when he arrived, the wheels fell off the deal.

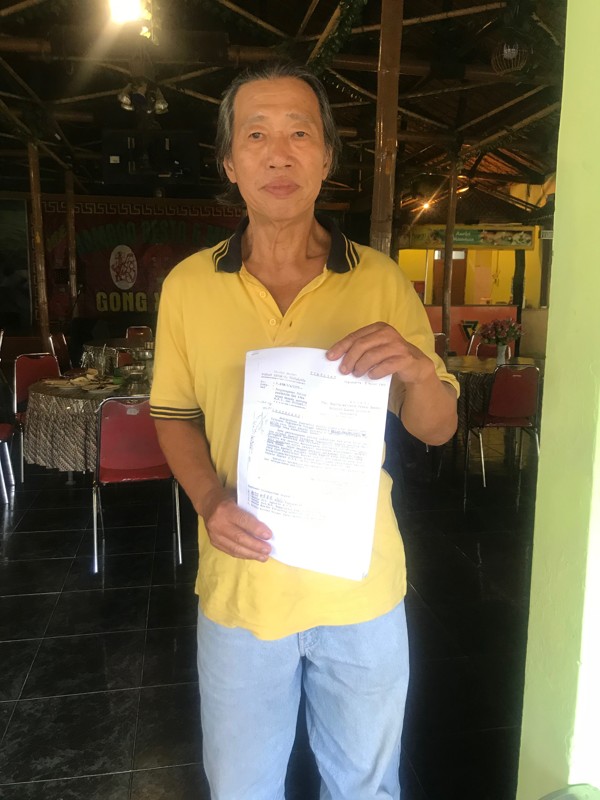

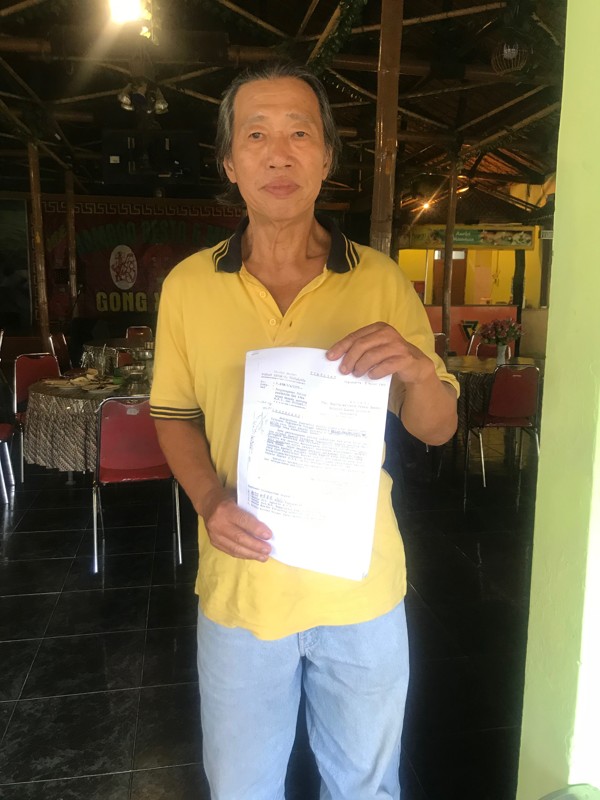

Sebastian was denied a land ownership certificate because he was a “non-native”. Instead, he was forced to sign a form relinquishing his rights to the plot. “It was very painful to see the land that we bought with our savings, from our hard work, unlawfully handed over to the government,” recalled Sebastian, 67.

He is one of countless ethnic Chinese who have been caught by an obscure policy prohibiting “non-native” ethnic groups from owning land in Yogyakarta, a special administrative region and sultanate on Java island.

The policy dates back to 1975, when the region’s then vice-governor Paku Alam VIII told officials not to issue land ownership certificates to Indonesians of Arab, Indian and Chinese descent on the grounds that this would prevent capitalists from exploiting the land of “native Indonesians” – the pribumi. The instruction stemmed from a decades-long perception that these ethnic groups – in particular the Chinese – were both well-off and well versed in exploiting their wealth. (Ironically, it was a draconian rule by the dictator Suharto barring Chinese from government or military posts that did most to establish their reputation for business acumen, as it meant they had little choice other than to develop their own businesses).

Under the 1975 policy, landowners of these ethnicities were asked to “voluntarily” downgrade their rights: from land owners to land users. Unlike land owners, land users must pay tax and lose their rights after a maximum thirty years. In issuing the policy, the sultanate referred to a hierarchy dating back to the Dutch colonial period that divided Indonesians into three classes – Europeans, East Asian migrants or non-pribumi, and native Indonesians or pribumi. Today, pribumi make up 95 per cent of the population.

Indonesia has taken steps to put this past behind it. The usage of the words pribumi and non-pribumi was banned after Suharto stepped down in 1998 and this was reinforced by a 2008 anti-discrimination law.

Yet discrimination continues in pockets such as Yogyakarta, where the land rights policy is implemented on an ad hoc basis. Sebastian, for instance, had no problem buying land soon after the reformasi that followed Suharto’s downfall. It was not until 2002, when he was relocating from the temple area and registered for a different plot, that he was informed of the policy.

The policy has often been challenged by Chinese Indonesians and even governmental agencies in Jakarta, but to no avail. The latest lawsuit was filed in September by a Chinese Indonesian named Handoko, a Yogyakarta-based lawyer, against the provincial land agency and Sultan Hamengkubuwono X, the region’s de facto governor. The court last month upheld the policy, ruling it was in accordance with good governance, as it was made to protect the poor against the rich. Yogyakarta officials welcomed the court’s decision, saying the policy was a form of positive discrimination. Suyitno, an expert witness in the case and an adviser to the sultan, told local media the instruction would be applied in Yogyakarta as long as the “equality gap remains high” . Handoko has filed an appeal.

This is not the first time Handoko has taken on the policy. In 2015 he asked the Supreme Court for a judicial review and a year later he went to Yogyakarta’s administrative court. Both cases flopped – the Supreme Court did not recognise the instruction as a statutory law; the other court said it was outside its jurisdiction.

Others have also tried, and failed. Sebastian, who leads the group Nation’s Children Against Discrimination, wrote in 2010 to then-president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, asking Jakarta to review the policy. Initially, things looked good: the national land agency instructed its subordinates in Yogyakarta to abandon the practice. Since then the same recommendation has been issued by the National Commission on Human Rights (twice), and the country’s ombudsman. All have been ignored. “I have also wrote to President Joko Widodo but there has been no reply yet,” Sebastian said. “This makes me wonder whether [Yogyakarta’s] governor is too powerful.”

Anti-Chinese sentiment has deep roots in Indonesia’s flawed past – there were anti-Chinese riots after the fall of Suharto on rumours Chinese were hoarding rice, while decades earlier hundreds of thousands were slaughtered after the abortive coup in 1965 that helped bring Suharto to power. For decades, Suharto had enforced a ban on expressions of Chinese culture, such as dragon dances.

That sentiment has flared in recent years, with increasing racial and religious tensions permeating the nation. Last month, a sword-wielding man attacked church-goers in St Lidwina church in Yogyakarta, injuring four people including a pastor.

In October, an event to mark the 500th anniversary of the birth of Protestant Reformation was cancelled after hardline Islamic groups said the service was a front to convert Muslims.

Tensions came to a boiling point last year during Jakarta’s gubernatorial election. The incumbent governor, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, an ethnic Chinese Christian, landed in hot water when a fake video purporting to show him insulting the Koran went viral. Ahok, as he is widely known, is now serving a two-year sentence in prison for blasphemy.

“Sometimes I wonder, ‘what is ethnic Tionghoa’s sin?’” Sebastian said, using a colloquialism for Chinese Indonesians. “Suharto’s oppressive rule for thirty-two years turned tionghoas into an inferior group, we were afraid to speak out. We finally found someone brave and vocal like Ahok, then they feared us.”

WATCH: Jakarta rally turns violent as Muslim hardliners attack police

Campaigners say one of the biggest hurdles in tackling discrimination over land rights is that many people are in the same position Sebastian himself once was – unaware that such a policy even exists.

Yogyakarta is, after all, good at papering over the cracks. A recent week-long festival in the tourist area of Malioboro celebrated the Lunar New Year. Among the acts was a group of hijab-wearing women singing Islamic chants and playing rebana, or Malay tambourines. “I like that there is a rebana performance, it shows we respect each other’s culture,” said Sari Puspita, a Yogyakartan who visited the festival. Like many in her hometown, Sari was unaware ethnic Chinese could not own land.

Nevertheless, campaigners cling to hope, though even Handoko is not optimistic things will change in his lifetime. “To me, it feels normal to be disappointed, but I will keep on fighting,” Handoko said.

“In the US, black people fought for their rights for hundreds of years. I think this country will still be racist even after I die.” ■