The small fishing town providing Japan’s nuclear litmus test

In the sleepy coastal town of Kaminoseki, population circa 3,000, one of Japan’s most divisive political debates – the future of nuclear power – is being played out in microcosm

The views from the sleepy coastal town of Kaminoseki could not be more contrasting. From the tip of the Murotsu peninsula on Japan’s Honshu island, one can glimpse the country’s pre-industrial past on an islet just a few kilometres offshore.

There, on Iwaishima, an elderly and dwindling population now down to just a few hundred fishermen, cling to a traditional way of life with little to disturb them bar the mating calls of migratory murrelets.

The view from Iwaishima is different. When the fishermen look back to the mainland they see the site of a long-stalled development that they say threatens far more than their rural idyll. It is here that one of Japan’s most divisive political debates – that regarding the future of nuclear power – is being played out in microcosm.

For the past 35 years, plans for twin nuclear reactors on mainland Kaminoseki have split opinion in this town of population roughly 3,000. When the plans were first unveiled by the Chugoku Electric Power Company in 1982, many on the mainland were wooed by financial incentives that included offers of compensation for the loss of fishing grounds. But those on Iwaishima have always remained almost unanimously opposed, staging protests on hundreds of occasions since then.

For the islanders, and many others across Japan, the meltdown of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in 2011 – triggered by an earthquake and tsunami – should have put an end to the country’s nuclear energy industry once and for all.

Yet slowly but steadily, the electric company is taking steps to resume the preparatory work it had been forced to halt in the aftermath of the disaster. By this summer, for the first time since 2014, the Japanese government will revise its strategic energy plan.

Not only will it look at restarting nuclear power reactors, it is expected to consider giving the green light to new facilities – a bold move Tokyo has avoided for years fearing a public outcry. Many see the future of the Kaminoseki plant – the only partially completed nuclear programme in the country – as a litmus test for Tokyo’s energy ambitions.

It is also, of course, something of a pivotal moment for Kaminoseki – which, at about 35 sq km, comprises Iwaishima, the Murotsu peninsula and two further islets. Iwaishima’s ageing population has been stalling the nuclear plant since 1982 in the face of a more business-minded approach by many on the peninsula, but how long it can continue to do so is unclear.

Proponents of the plant say it will offer Kaminoseki the kind of development that has long passed the town by. Kaminoseki boasts neither rivers nor plains, a geographic quirk that meant it was left out of the post-war double-digit growth enjoyed by many of its coastal peers that were transformed into industrial zones.

For those on Iwaishima, and others against the reactors, this lack of development is one of the island’s greatest assets. They want the government to scrap the project to preserve Iwaishima’s pristine environment, which in addition to the murrelets is home to numerous threatened species.

Fabled by sailors as “Japan’s Mediterranean”, the Seto Inland Sea in which Iwaishima sits is a hotspot for many migratory bird and fish species thanks to an upswelling of currents from both the Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Japan. Midori Takashima, a leading figure in the battle to stop the nuclear development, fears the reactors would upset Kaminoseki’s “miraculously maintained” ecosystem.

Safety is another concern, particularly for the elderly on Iwaishima. Ships leave for the mainland just three times a day and are often put out of service by summer typhoons or winter gales, making a smooth evacuation in case of a nuclear emergency extremely doubtful.

Those against the plant have some big names on their side, not least among them Junichiro Koizumi, a former prime minister who has called for Japan to be nuclear free. While the sitting prime minister, Shinzo Abe, appears likely to continue embracing nuclear power, Koizumi has said he is hopeful Japan’s next leader will get rid of nuclear power once and for all – including the Kaminoseki project.

IT’S THE ECONOMY, STUPID

The more sizeable pro-nuclear camp on mainland Kaminoseki takes an opposite view. “This is simply investment promotion. Not many companies are willing to come here,” says Tadanori Koizumi, an executive director of a pro-nuclear civic group.

He fears the effects of Kaminoseki’s declining population, as its youth continue to stream to the cities in search of work. Kaminoseki’s headcount has shrunk to a little over 2,800 – less than half what it was when the project was first unveiled.

“Our town’s very survival is at stake”, he says.

Kaminoseki, like other towns accommodating nuclear plants, has received generous government funding in return – at one point the central government was providing the town 500 million yen (US$4.7 million) annually in nuclear related subsidies, while Cepco has donated a total of 2.4 billion yen.

Such incentives have been likened to bribes by Cepco’s opponents. Cepco, for its part, argues that as a listed company it must ensure a balance in its projects, between expensive fuel-based power generators and more effective nuclear power ones.

A Cepco official said building a nuclear plant in Kaminoseki had been a “dearest wish” for the company, given its low dependency on nuclear power in contrast to other electricity companies in Japan.

“We want to coexist and co-prosper [with Kaminoseki],” said the official – though he admitted, via an analogy with the aviation industry, that 100 per cent safety could never be guaranteed.

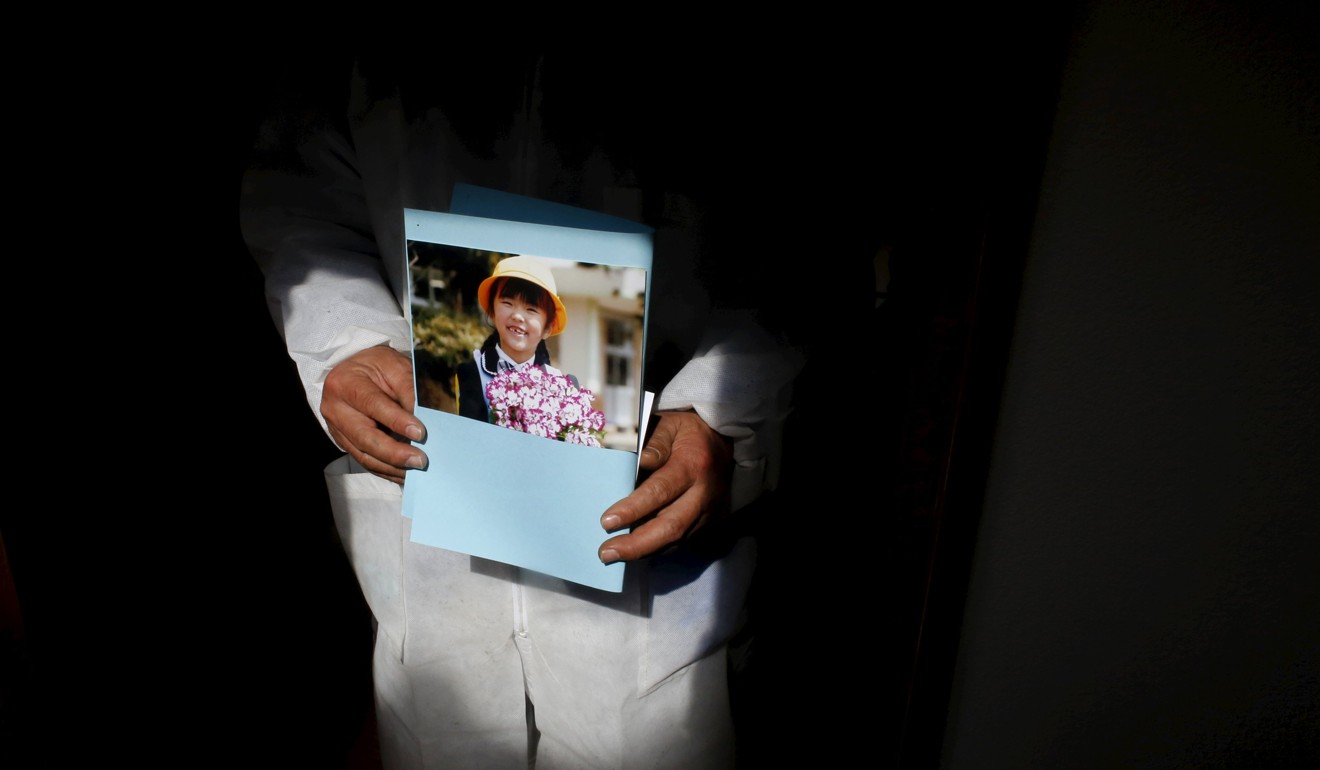

Other than waiting for a terminal decline in Iwaishima’s demographics, it’s hard to see how the two sides can ever reconcile. As Toshiyasu Shimizu, the leader of the anti-nuclear campaign in Kaminoseki, explains, tensions over the issue escalate whenever there are elections.

The town has a habit of returning pro-nuclear mayors and most of its council members remain in favour of nuclear power. “When it escalates, the confrontation appears even between relatives, between parents and children,” he says.

Cepco has sued Shimizu and three of his fellow activists, seeking damages of around US$400,000 over their attempts to block preparatory construction work. But even Shimizu recognises the need to boost Kaminoseki’s economy. “The residents are not supporting or opposing the project because it is good or bad,” he says.

“Rather, their attitudes are formed by human relations, their jobs or the local economic structure.”

He says the town must rebuild its economy without turning to the nuclear energy industry, and suggests selling the locally produced delicacy hijiki – a brown sea vegetable – across the country.

“If the nuclear power project is completely gone one day, then that marks the start line,” says Shimizu.

“Then we can start thinking about the future of our town.” ■