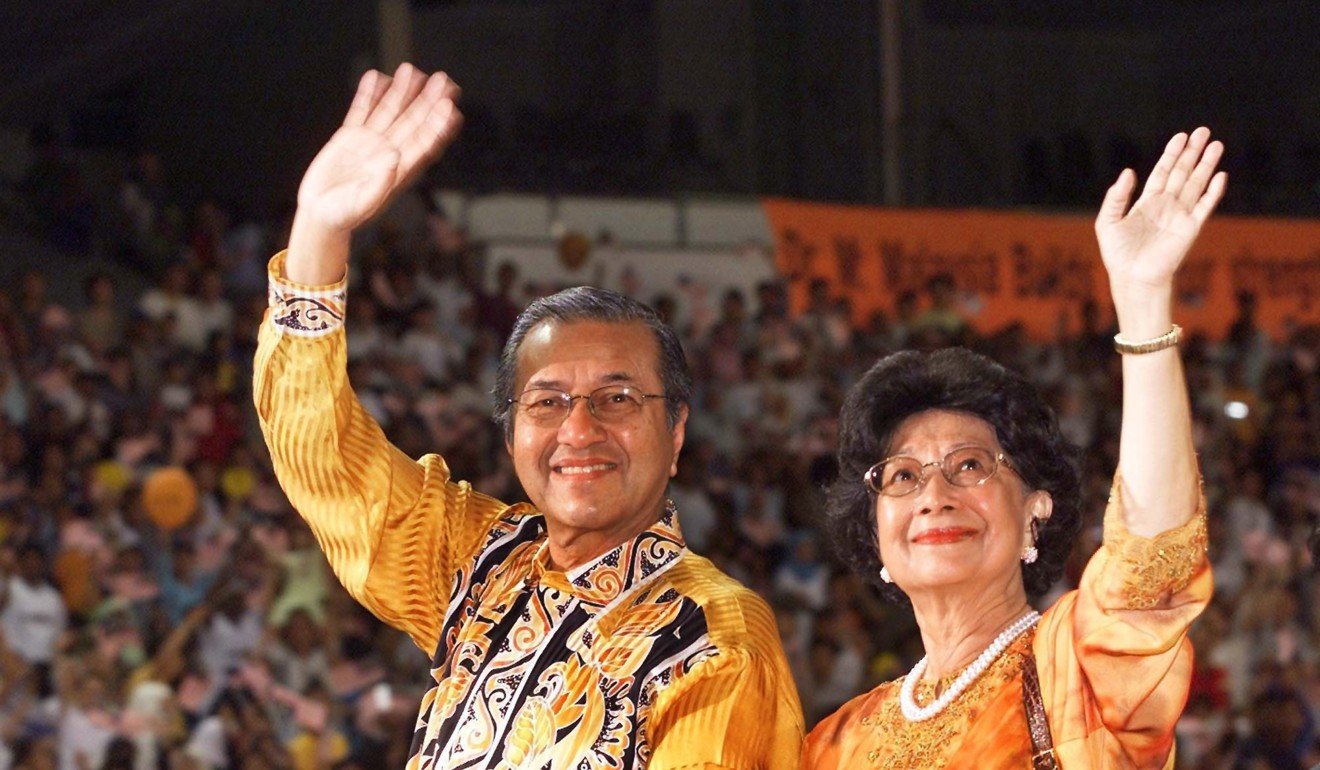

Mahathir, the Malaysian dictator who became a giant killer

He’s been called a dictator and a moderniser; a racist and father of the nation. Now, with his shock election victory over former protégé Najib Razak, the Malaysian strongman has a new label: giant killer

After two decades as Malaysia’s prime minister, during which time he sacked dissenting judges, censored inconvenient journalists, and dismissed various human rights issues, Malaysia’s longest-serving prime minister is back for a second crack at the job.

On Wednesday, 92-year-old Mahathir Mohamad ushered in a nail-biting victory for opposition alliance Pakatan Harapan, leading its component parties to a convincing victory by scooping up 113 of 222 total parliamentary seats, bringing the decades-old Reformasi (reformation) movement to Putrajaya.

The irony, of course, being that there would have been no Reformasi without him – but Mahathir’s career has been full of such ironies.

Born the youngest of nine children in Alor Setar, Kedah, British Malaya in 1925, Mahathir was politically active from a young age, frequently speaking out for Malay rights during his university years in what is now the National University of Singapore.

Upon his return to Kedah, he became active in the United Malays National Organisation (Umno) and was elected to parliament in 1964. His bickering with then-prime minister Tunku Abdul Rahman, is thought to have delayed his first campaign for public office and hastened his exit when he subsequently lost re-election. Mahathir was expelled from the party for criticising its leadership and left in the political wilderness.

But Mahathir, known by some as “Tun M” or “Che Det”, excels at returning from the dead. He made MP in 1974 and was appointed to cabinet by the next prime minister, Abdul Razak Hussein – father of the man he beat in the polls this week.

From there, the course was set and his rise to power meteoric. But what shocked many was his turbulent relationship with his former deputy Anwar Ibrahim. Known for their father-and-son-like closeness, few would have anticipated the acrimony that accompanied their split.

After sacking Anwar in 1998, Mahathir denounced him as “morally unfit” for leadership. Allegations of sodomy and corruption followed Anwar and he was put on trial. During the proceedings, Mahathir pronounced him guilty on television.

Anwar was jailed for up to nine years, charges he maintains were trumped up because of his objections against corruption on Mahathir’s part. But Anwar’s political and personal persecution ignited the Reformasi movement, a slew of mass protests against Mahathir’s government that led to the formation of Parti Keadilan Rakyat. Together with the Democratic Action Party and Parti Islam se-Malaysia (PAS), they formed the first true threat to the Barisan Nasional coalition, which until this week had led the country for decades.

Anwar’s coalition would erode the BN’s dominance and its two-thirds majority in parliament in 2008.

Mahathir, tired of his hapless successor Abdullah Badawi, pushed for his removal by quitting Umno and vowing not to return until he was gone.

Enter Najib, 64, Abdullah’s successor. And while Mahathir continued to serve as his adviser, bully, and mentor, enjoying his retirement while keeping one hand on the wheel; over time the allegations of Najib’s corruption became too much to ignore.

Mahathir took a stand once again, this time not through a hand-picked proxy – there were few remaining who could meet his standards – but by entering the fray himself. He registered a new political party and joined the new opposition coalition, becoming the most vocal critic of those he had formerly collaborated with. In public utterances, he almost relished the role reversal.

Behind the grandfatherly demeanour and soft-spoken voice was ruthless determination, and age had done little to dull his wits.

“You know I used to be the Umno president?” he was quoted as saying after a slip of the tongue where he mistakenly urged voters to back his old party instead of Pakatan Harapan, correcting himself a moment later.

“Now I am trying to bring down Umno.”

Embracing the mantle of opposition leader, with Anwar in jail for a second time, he turned on BN and was in turn roundly criticised by both his former party, but also Malaysia’s monarchs. The Sultan of Johor slammed Mahathir for “playing the politics of fear and race” while the Sultan of Selangor described the erstwhile premier as “an angry man and will burn the whole country with his anger”.

Mahathir responded with his trademark sarcastic wit, saying “Yes, I am a very angry man, you can see how angry I am. I will burn you, I am always burning things.” He followed this up with returning titles he had received from the palace; because Mahathir’s conviction often accompanies scorched earth.

Mahathir was known for his sceptical view of human rights. His rule saw the infamous 1987 Ops Lalang, where police cracked down on activists, politicians and students, and newspapers had their publishing licences revoked. He punished states that stepped out of line such as withholding oil royalties from the state of Terengganu when residents elected an opposition party to government. He approved construction of the Bakun Dam in Sarawak, a project which displaced several thousand indigenous people. The speed with which he dealt with detractors earned him the moniker ‘mahafiraun’.

Mahathir’s relationship with Western powers and his history of anti-Semitic comments earned him a reputation as an irascible strongman in foreign media. Anti-Jewish comments at a meeting of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference in 2003 earned him a White House rebuke.

He cultivated a Look East policy and was loudly critical of Western countries and their “arrogance” on all levels – in an infamous letter to a 10-year-old English boy who had requested that Mahathir stop felling rainforests, he wrote back “When the British ruled Malaysia they burnt millions of acres of Malaysian forests so that they could plant rubber … What your father’s fathers did was indeed disgraceful. If you don’t want us to cut down our forests, tell your father to tell the rich countries like Britain to pay more for the timber they buy from us. Then we can cut less timber and create other jobs for our people.”

Mahathir’s relationship with Singapore was equally complicated, jousting over issues such as the use of Malaysian airspace and the city state’s land reclamation efforts. He was critical of Lee Kuan Yew for his application of the democratic process, saying “He goes through the formalities, but if there are any opposition politicians elected, he makes sure that they will be incapacitated, and the suits will be settled with huge payments, compensation and all that; or the opposition will come in and be very quiet and not say anything.”

However, after the death of Lee, Tun M expressed sadness.

“I cannot say I was a close friend of Kuan Yew. But still I feel sad at his demise … His passage marks the end of the period when those who fought for independence lead their countries and knew the value of independence.”

Former Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir to return to power after opposition wins election

Mahathir’s fiercely protective attitude towards Malaysia extends from criticism of British rule to its newly strengthened economic ties with China. Although in Mahathir’s tenure he viewed China as an important trading partner, recent moves such as the sale of Proton to Geely and land to Chinese developers appear to cross a line: he expressed the belief that some deals would have to be renegotiated despite his overall support for the Belt and Road Initiative, and in a blog post said that Malaysia was selling its land to foreigners to settle its debts.

“The Chinese are welcome to invest in industries in Malaysia. But just as we would not welcome mass immigration of Indians, or Pakistanis or Europeans or Africans into Malaysia we have to adopt the same stance on Chinese immigration into Malaysia … It is not about being anti-foreign or anti-Chinese. It is about being pro-Malaysia … Local businesses, largely Malaysian Chinese owned, will definitely lose out to those of the mainland Chinese,” he wrote on his blog last year.

And all his human rights trespasses were momentarily laid aside by the voters on Wednesday night – helped in no small part by his legacy as part of the old guard of Asian politics and grandfather of the nation. A large portion of the Malaysian electorate possess lasting affection and respect for him because of various successes. Mahathir engineered rapid economic growth. He shifted the country’s economy from agriculturally based to a more industrialised one. He created a sense of civic and national pride through projects such as national car Proton, the Sepang Formula One circuit and, of course, the Petronas Twin Towers, still the tallest twin skyscrapers in the world. And while detractors have their doubts, Mahathir has made several allusions to his chequered rule, including most recently a short film where he explains to a child that he has made mistakes.

“I am already old,” he tells her, his eyes welling with tears. “I haven’t much time left. I have to do some work with regards to rebuilding our country; perhaps because of mistakes I myself made in the past and because of the current situation.”

Love him or hate him – and there seem to be very few bodies who fall in the middle of that spectrum – anyone would be hard pressed to deny that Mahathir has nothing but fierce love for Malaysia. Some would argue he views the nation as a foil to his ego, but patriotism remains patriotism, and the chipping away of Malaysia’s legacy – Mahathir’s legacy – strikes a chord with the nonagenarian.

“Proton can no longer be national. No national car now. We Malaysians are glad to be rid of this pesky car … I cry even if Malaysians are dry-eyed. My child is lost. And soon my country,” he wrote in 2017, when Proton was sold.

And after half a century of BN, Mahathir’s definition of independence is sure to strike a chord with the voters who gave him the mandate yet again:

“Independence means we enjoy freedom. We are not colonised by people. And we can govern our own country and develop it independently so that our people can live a better life.”