Old Mahathir Mohamad was not always pals with Singapore. What about the new one?

Relations between Malaysia and Singapore went through a thawing period under Najib Razak, but things might get cool again as Mahathir Mohamad – and his ‘my way or the highway’ approach – returns to power

Does Mahathir Mohamad’s return to power in Malaysia mean Singapore will soon find itself fending off – once again – the veteran leader’s grand plan for a so-called crooked bridge between the two countries?

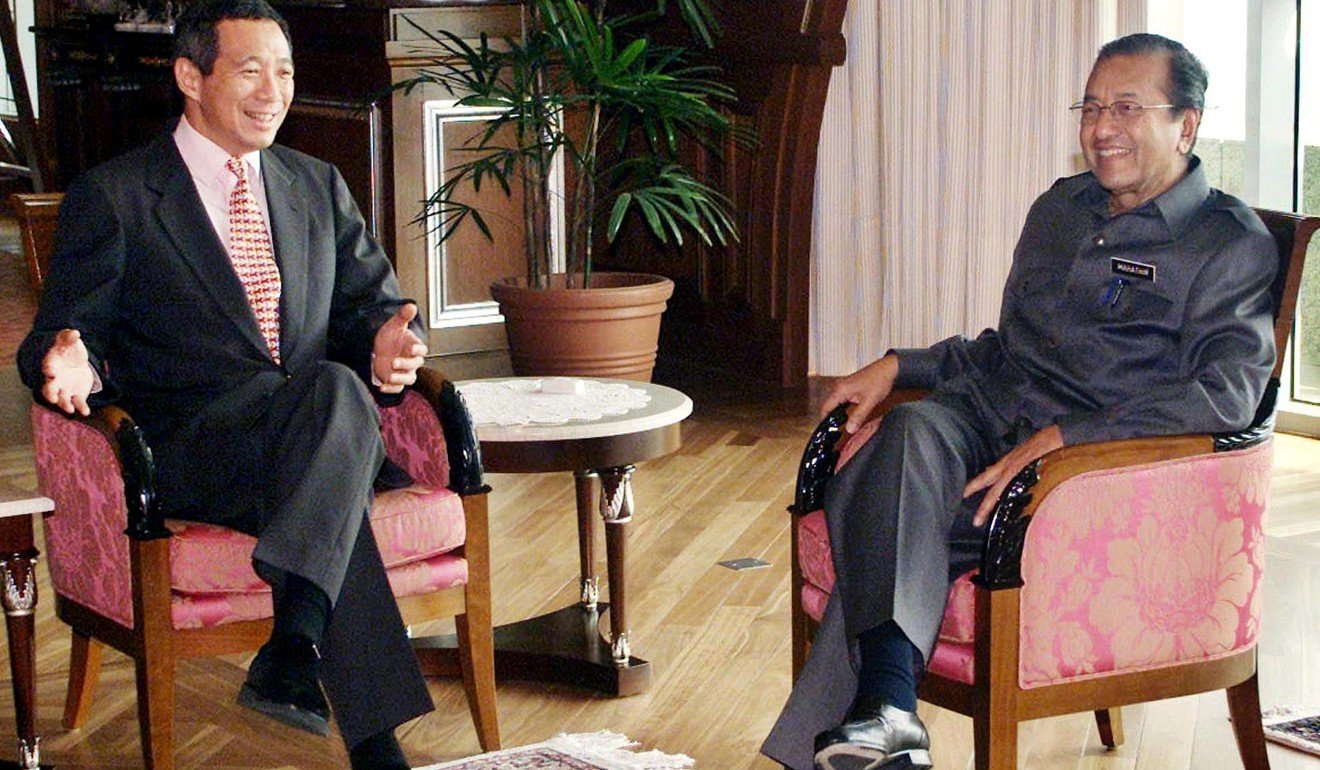

Mahathir’s second time at the helm as prime minister is not only rattling Chinese investors. Singapore, which endured periods of being his main whipping boy during his turn as premier from 1981 to 2003, is having anxieties of its own. The crooked bridge is one of several projects pundits and policymakers are watching as they try to anticipate how ties will change between the neighbours – which were one country before they split in 1965.

The idea for the bridge dates back to 2001, when Mahathir wanted to replace the 1km causeway that links Malaysia and Singapore with a bridge to improve traffic flow and – crucially for the Malaysian economy – allow ships to cross the Johor Strait, providing a boon to the ports in Johor, Malaysia. Singapore never agreed, saying the project was unnecessary because the causeway was in good condition.

Experts often cite Mahathir’s insistence in the following years on building a six-lane, curved motorway, or crooked bridge, on Malaysia’s end of the causeway – to circumvent Singapore’s reticence – as a prime example of his “my way or the highway” approach to dealing with the city state.

The plan fell through during the tenure of his successor Abdullah Badawi, and when the just-beaten Najib Razak took over in 2009, he too refused to take up the cudgels for Mahathir’s bridge plan.

In an interview with This Week in Asia last year, Mahathir said his approach to Singapore was grounded on one fundamental rule: “As far as Malaysia is concerned, Singapore is a foreign country.”

“If we want to do anything inside our country, we don’t have to ask anyone for permission,” he said.

At a press conference on Thursday, Mahathir said he had no firm plans on what he wanted to discuss with his Singaporean counterpart Lee Hsien Loong, who is due to call on the newly sworn-in Malaysian leader on Saturday.

The crooked bridge, and the future of a mooted high-speed rail link between Singapore and Malaysia, could be on the agenda, observers say.

The rail link’s future is being closely watched because Mahathir has said he will review all major infrastructure projects signed by the Najib administration, which was haunted by scandal. While the tender for the project has yet to be won by any of the competing parties – Chinese, South Korean and Japanese players are all in the fray – Singapore has already sunk considerable resources into the project, including acquiring private land where the line’s terminus will be located.

Singapore’s Lee said he was visiting Mahathir to “tell him that I look forward to working with him again for our mutual benefit”.

Eugene Tan, a Singaporean political observer, said there was probably anxiety in the Singapore government “beneath the warm congratulatory messages”.

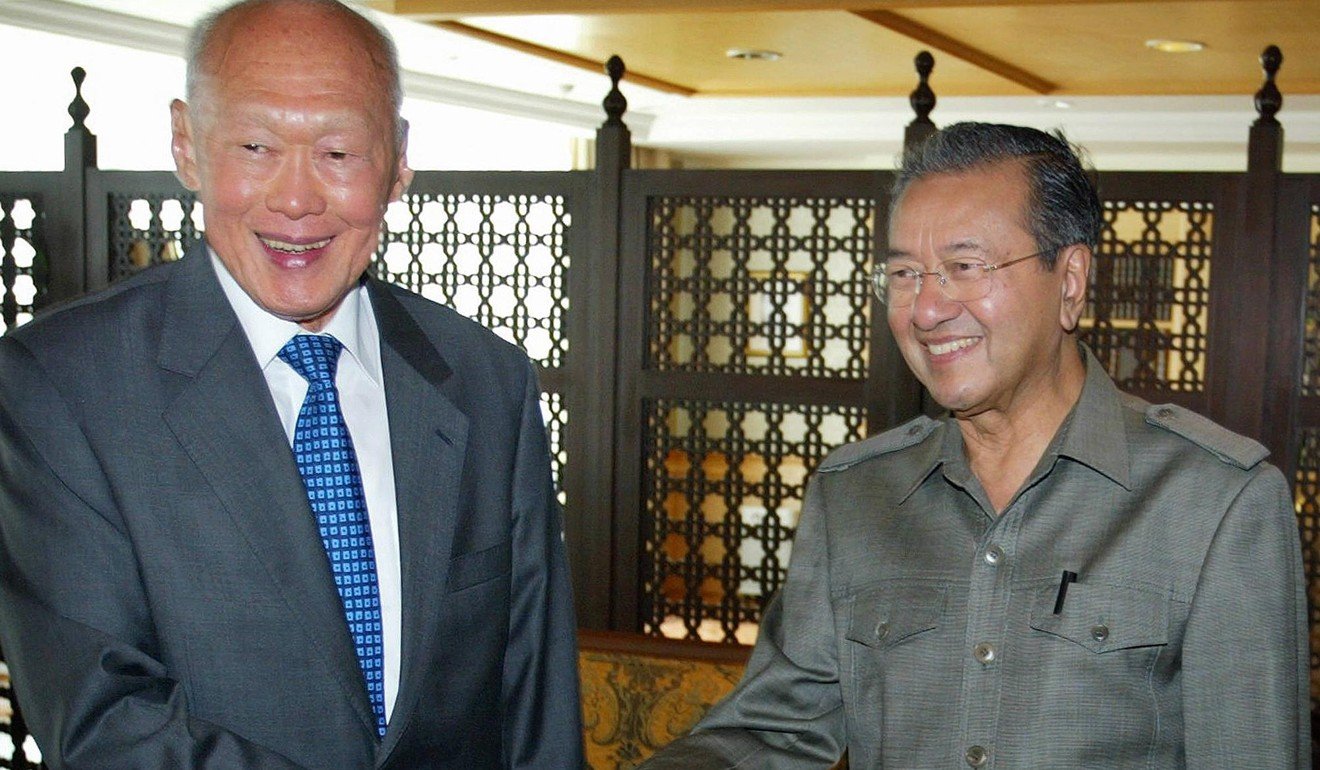

Mahathir and Lee’s father, founding prime minister Lee Kuan Yew, had a long fractious history, first clashing when they were in the Malaysian Parliament in the 1960s, and then as counterparts trying to steer their countries and negotiate several pacts. But when Lee died in 2015, Mahathir paid tribute, saying “there was no enmity, only differences in our views” in those early days.

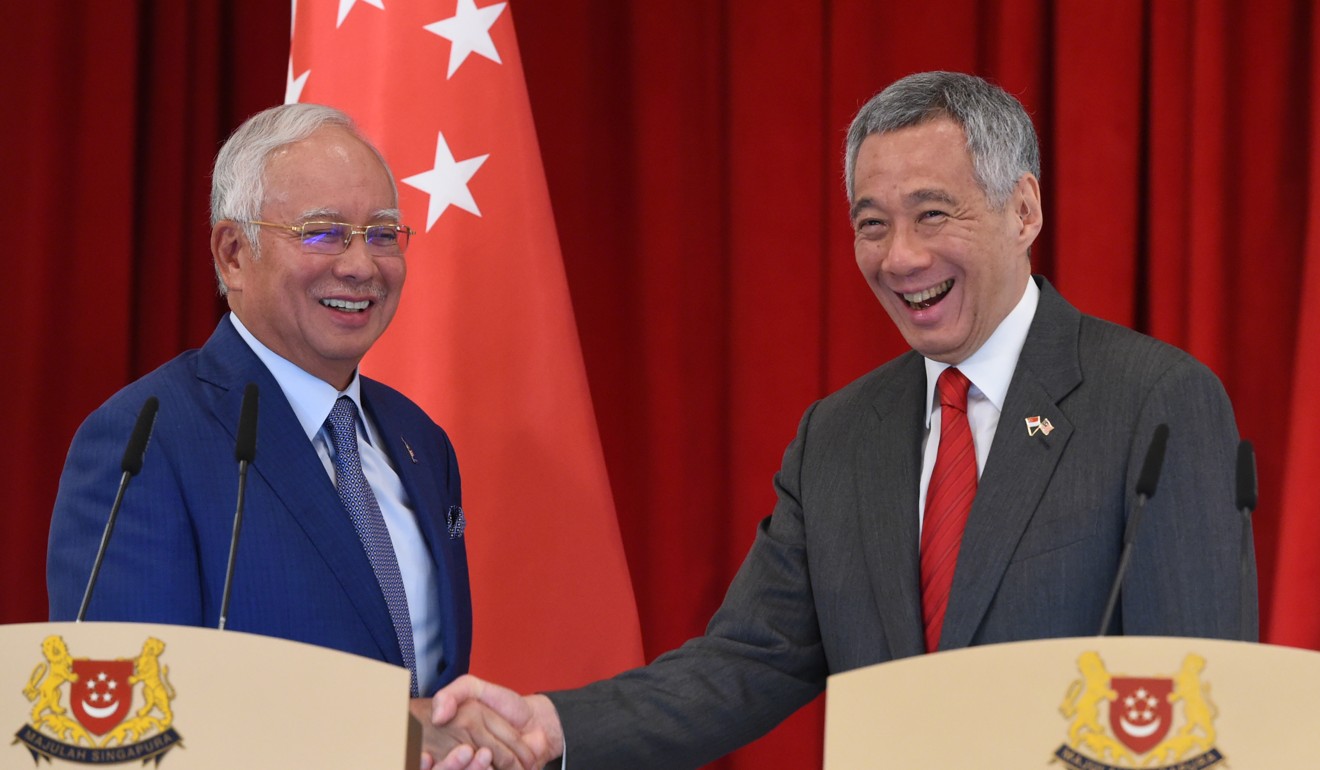

Perhaps because of the acrimonious separation in 1965 and the litany of outstanding issues – Singapore, for example, still buys water from Malaysia – the relationship has always been stilted. But the atmosphere improved during Najib’s tenure. Both the younger Lee, in power since 2004, and Mahathir’s protege-turned-foe Najib, who is under investigation for alleged links to the multibillion 1MDB state fund financial scandal, got along and made progress on several issues.

In 2010, Najib and Lee signed a landmark agreement over the ownership of Malaysian-owned railway land in Singapore – the last of sticking points between the two countries in the “Mahathir 1.0” era.

Such progress was in stark contrast to the 1990s, when Mahathir and the Singapore administration helmed by Premier Goh Chok Tong sparred over a myriad of issues including air space, the sale of Malaysian sand to Singapore, and the price the city state was paying for Malaysian water.

The warm relationship between Najib and Lee has become a talking point after the stunning election defeat of Najib and his Barisan Nasional coalition. This week a video from a January press conference circulated online showing Lee and Najib exchanging lighthearted remarks about the election.

The rapport would have been unimaginable between Mahathir and Goh, or Lee Kuan Yew. “I don’t expect elections to change the nature of relations between our two countries,” Najib said, to which Lee immediately replied, drawing guffaws from the Malaysian leader: “Because you have a confidence in the result!”

One hurdle for Singapore in dealing with the new Malaysian administration could be the lack of “careful cultivation of politicians beyond the Barisan Nasional fold”, said Tan, referring to Najib’s defeated coalition which had ruled Malaysia since independence from Britain in 1957.

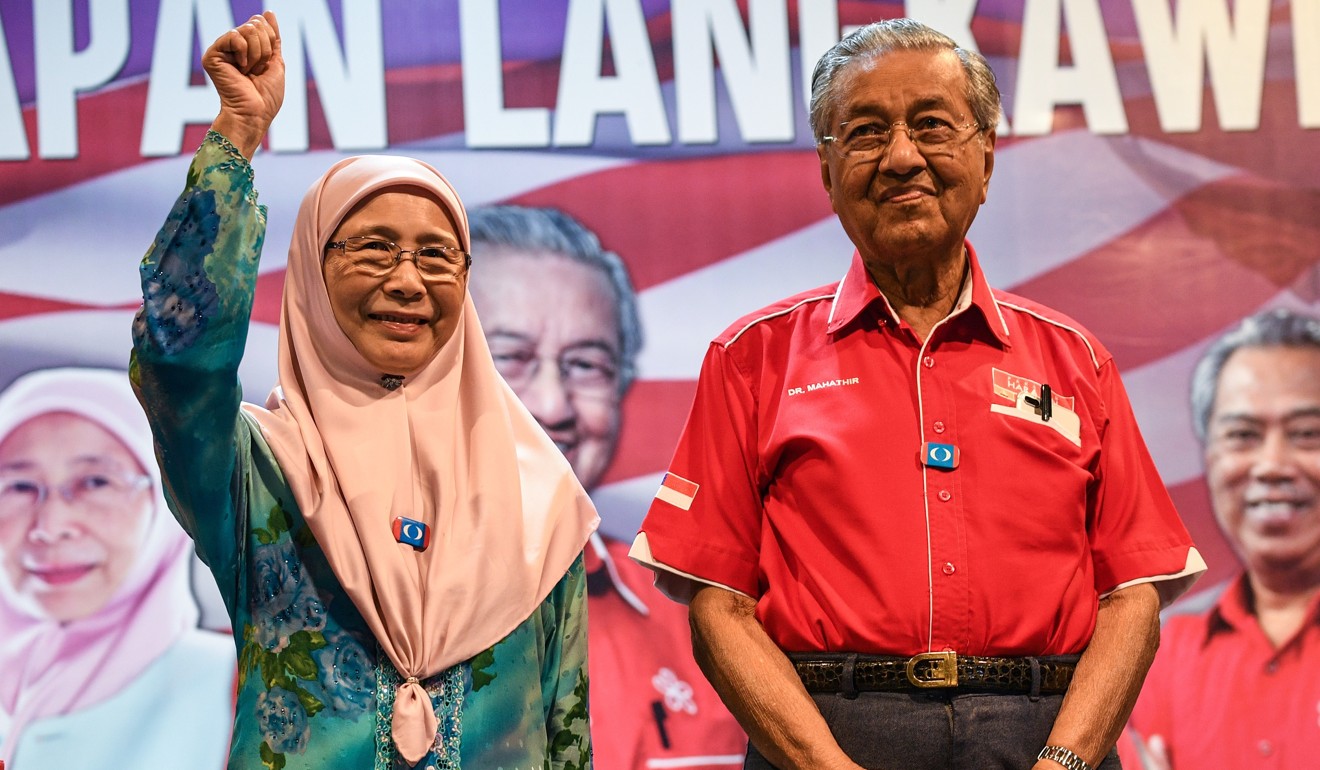

Tan said Lee was likely to make overtures with Anwar Ibrahim, the ruling Pakatan Harapan bloc icon who was released from jail last week.

The alliance has pledged to make Anwar, a protege-turned-nemesis-turned ally of Mahathir, premier within two years. His wife Wan Azizah Wan Ismail is the current deputy premier.

“Much is at stake for both countries, more so for Singapore, and so this trip is an important one, Tan said. “Singapore’s priorities are to maintain bilateral relations on an even keel and maintain the momentum that was built up during the Najib term.” ■