Tensions among Indonesia’s security forces simmer beneath surface after Jakarta’s election riots

- The clashes in May highlighted a power struggle in the armed forces as well as a deep rivalry between the military and police

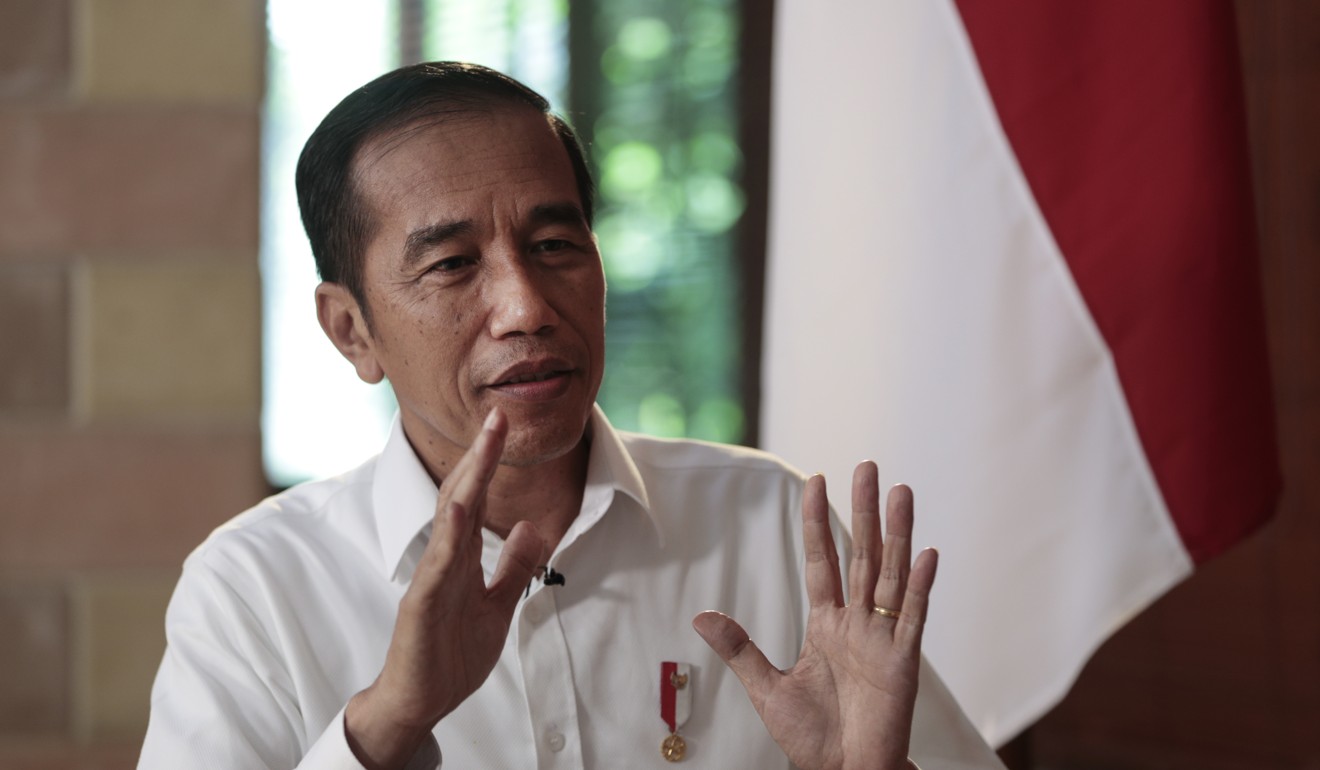

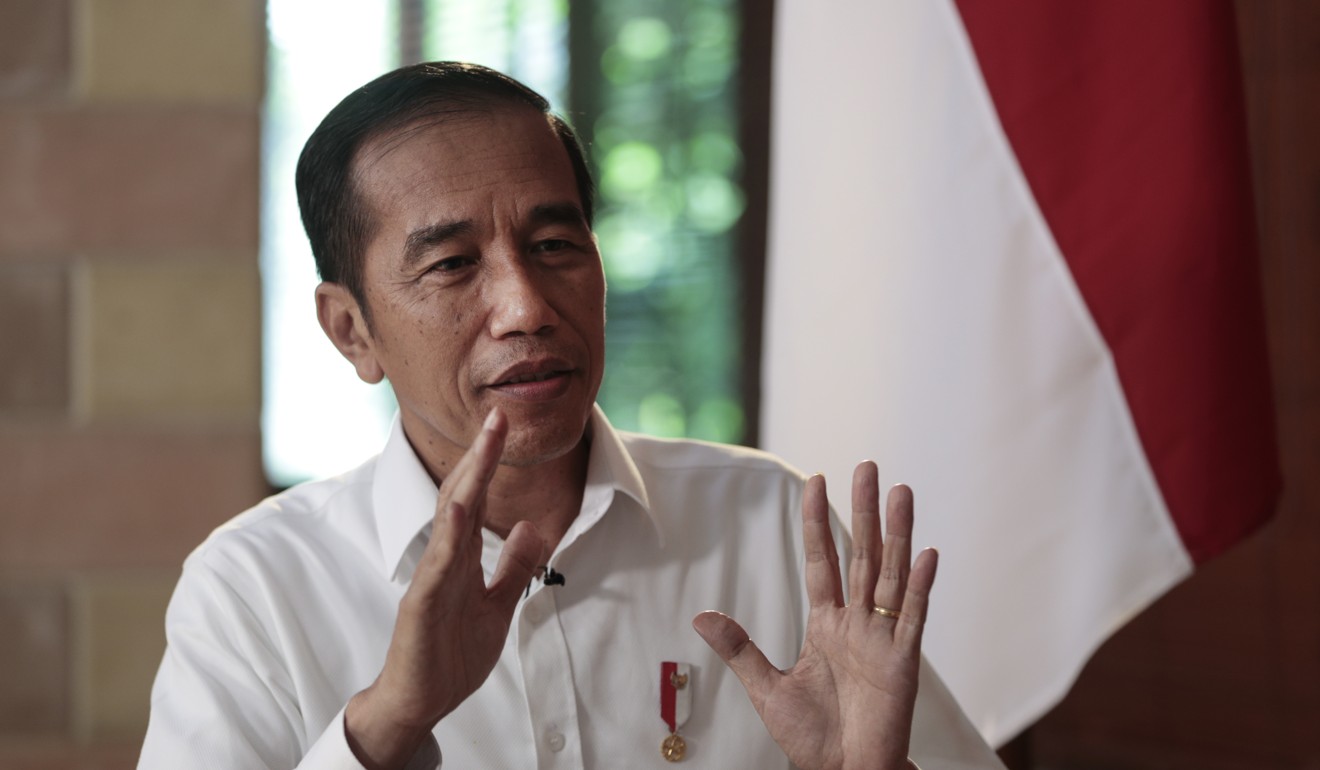

- For President Joko Widodo, the delicate task is to curb the infighting before it becomes a crisis for his government

Indonesia’s riots over the disputed presidential election this year were the worst since the 1998 unrest that toppled long-time strongman Suharto. Though the polls triggered the violence, there were also more deep-seated reasons for the two days of chaos.

Behind the scenes a power struggle was taking place among retired army generals backing the different presidential candidates – a battle with clear echoes of the ideological factionalism seen in the final years of Suharto’s rule.

Muslim-oriented officers were butting heads with those from nationalist and secular quarters as well as religious minorities including Christians, Hindus, and Buddhists.

Most of the former supported losing candidate Prabowo Subianto and the latter incumbent President Joko Widodo, popularly known as Jokowi.

But the riots also brought to the fore increasing tension between the military and police – a rivalry which has long plagued Indonesia’s security sector. Widodo has allied himself more with the police force, affording it greater access to the levers of power.

BALANCING ACT

Many of the divisions today remain from the days of Suharto, who was very skilful in creating factionalism and maintaining the balance between groups.

In the last days of the country’s so-called New Order, the military was divided into “green” and “red and white” factions. The greens tended to be Muslim conservatives who wanted to keep the military in power, while the “reds and whites” were reformists eager to limit the role of the armed forces and focus instead on military professionalism.

To balance power, Suharto appointed close confidantes to the highest military offices, but he also elevated his son-in-law and darling of the conservative faction Prabowo to commander of the army’s strategic command.

Today these now retired generals still see their support for Prabowo as a way to gain a share of political power, and there is no doubt these officers played a role in the protests over suspected fraud after May’s electoral run-off between Prabowo and Widodo. They provided significant political aid to Prabowo’s civilian supporters, and were active in organising demonstrations and giving speeches. Some have even been accused of violence.

Though they have no official power, they retain influence as former “warriors of the country”. Their criticism of the election results therefore called into question the legitimacy of the Widodo administration.

WHO’S IN CHARGE OF SECURITY?

Adding another layer to the political tussles is the military’s rivalry with Indonesia’s police force, which was on full display in the days immediately before and after the riots. On May 21, police detained Major General Sukarno on a charge of smuggling firearms.

Major General Kivlan Zen meanwhile, a conservative military general, was accused of planning to assassinate several members of Widodo’s cabinet and some civilians. Police arrested a number of suspects and accused Zen of being the mastermind. Zen is a controversial figure and is popular among Muslim hardliners, but his arrest did not spark criticism from retired generals.

It was different however where Sukarno was concerned. His case sparked an uproar among generals inside Widodo’s administration, who called his detention harassment and defamation of the military.

When the riots broke out, the distrust between the armed forces and police was on full display.

There are strong perceptions within the military that Widodo has allied himself with the police, and that the force has been helping the government control the opposition.

The way Widodo handled the May riots showed he is increasingly dependent on the police for matters of security. He trusts the chief of police, General Tito Karnavian, and has expanded police power by using officers to resolve political issues. In this sense, the police to Widodo is like the army was to Suharto’s government.

WIDODO’S WORK CUT OUT

The split between the military and police is also apparent in Widodo’s cabinet. Military aides to the president have lobbied for Sukarno to be released and his firearms smuggling charge dropped. They have not however lobbied for the release of Zen, the Prabowo loyalist.

The next challenge for Widodo may come from retirees who have joined the Nation Sovereignty Forum, a group with broad influence among retired army officers. Issues of contention within the military are very likely to be exploited by this group in the future for political and economic gain.

Given Indonesia’s strong culture of patronage, these tensions threaten to break out into open conflict during Widodo’s second term of office, and a delicate balancing act will be needed on the part of the president to prevent a political crisis or even more violence.

Made Supriatma is a visiting fellow in the Indonesia Studies Programme at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore. This is an edited version of an article published in the ISEAS Perspective 2019/61 “Tensions Among Indonesia’s Security Forces Underlying the May 2019 Riots in Jakarta”.