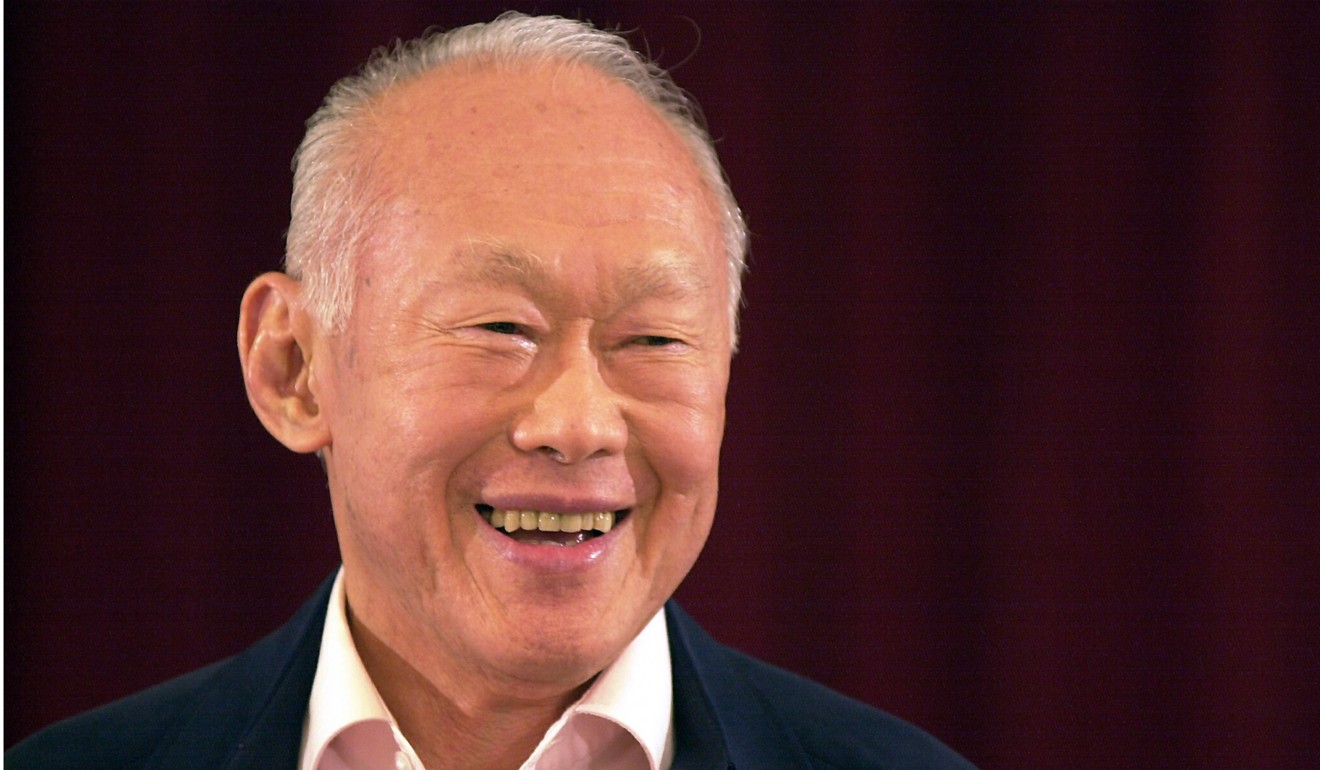

Hong Kong campus protests: what would Lee Kuan Yew do?

- As battles raged in Hong Kong universities, remarks by the late leader on how he handled student protesters spread on WhatsApp

- But while Singapore’s methods were effective in the 1960s, an expert says a different tack is now needed

As pitched battles raged between masked protesters and police across three Hong Kong university campuses in recent days, quotes by the late Singapore leader Lee Kuan Yew were being shared in WhatsApp groups by some residents in the Chinese city.

The remarks – made by Lee about the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown – were accompanied by exchanges on what he might have done about the campus occupations, where radicals unleashed petrol bombs and other makeshift weapons as police fired volleys of tear gas and rubber bullets to flush them out.

Lee had recounted to Time magazine in 2005 what he told former Chinese premier Li Peng, who became known as the “Butcher of Beijing” for declaring martial law on the Chinese capital amid pro-democracy protests by students.

“When I had trouble with my sit-in communist students, squatting in school premises and keeping their teachers captive, I cordoned off the whole area around the schools, shut off the water and electricity, and just waited,” he said.

“I told their parents that health conditions were deteriorating, dysentery was going to spread. And they broke it up without any difficulty.

“I said to Li Peng, you had the world’s television cameras there waiting for the meeting with [then Soviet leader Mikhail] Gorbachev, and you stage this grand show. His answer was: ‘We are completely inexperienced in these matters’,” said Lee, who led the city state from 1959 to 1990.

Singapore’s first prime minister, who died in 2015, was referring to the experiences he had with student demonstrations in his early years in government.

Campus political activism in the Lion City peaked in the 1950s and 1960s, first fuelled by anti-colonial sentiment and later by a split in Lee’s People’s Action Party (PAP), which led to a breakaway faction of mostly Chinese-educated trade unionists forming the Barisan Sosialis (Socialist Front).

From the PAP’s view, the new opposition party – which contested the terms being discussed for Singapore’s merger with Malaysia – was made up of communists influenced by their counterparts in Beijing.

The Barisan Sosialis had support from students and workers, and as historian Huang Jianli described it in a chapter in Paths Not Taken: Political Pluralism in Post-war Singapore, “full mobilisation of this opposition front was activated” when the PAP government announced changes to the Chinese school system after coming to power, frustrating educators and students who feared the demise of Chinese education.

Chinese middle-school students and the student union at what was then Nanyang University, which had been established through donations by members of the Chinese community from all walks of life, launched a boycott of year-end examinations in November 1961. Local media reported masked students picketing outside schools and forming human chains to prevent others from taking the exams.

Lee later recalled in his memoirs: “This was part of the general turmoil the communists sought to create. They wanted the Chinese school students into the act … but we refused to use the police to break up their picket.”

Instead, the PAP government made the police stand back and placed parents at the front lines of confrontation. They were told their children would lose out if they did not take the exam, with then education minister Yong Nyuk Lin suggesting they “assert their parental authority by going to the picket lines and taking their children home. It is not the government’s intention to give communists an excuse to say that police are manhandling students”.

In the end, concerned parents helped their children enter the exam centres, and nearly two-thirds of the 3,000 students required to take the examinations completed them, according to political analyst Bilveer Singh in his 2015 book on communist subversion in Singapore.

Later episodes of campus activism were fuelled by politics and opposition to government policy, with classroom boycotts and protests at the Nanyang University campus.

Between 1963 and 1965, the authorities raided the campus several times to detain students and alumni. They later used other methods to curtail student activism, including a 1975 amendment to the University of Singapore Act that nullified the autonomy of university student unions.

SPARK PLUGS FOR CHANGE

Unlike Singapore, several cities across Asia saw periods of campus activism in the 1980s where youngsters “acted as spark plugs for sweeping political change later”, said political scientist Alan Chong, who teaches at the Nanyang Technological University – which was founded in 1991 on the former Nanyang University campus.

These included demonstrations aimed at bringing down dictatorships, such as the 1986 People’s Power Revolution in the Philippines, a series of protests in Manila against alleged electoral fraud and abuse by the administration of president Ferdinand Marcos.

In 1980, South Koreans in the southwestern city of Gwangju rallied against the state of martial law that had been in place since a coup the year before brought down dictator Park Chung-hee. For Cho Sun-ho, a 56-year-old official of a pro-democracy non-profit in South Korea, the battle between police and protesters at Hong Kong Polytechnic University reminded him of the Gwangju uprising.

“It all escalated like that. There were some clashes between riot police and protesters and then swaggering martial-law troops stepped in and brutally attacked protesters, sparking the bloodbath,” said Cho, who was a high school student then.

The 10-day uprising ended with more than 200 killed and thousands injured, but paved the way for further pro-democracy struggles in the country.

In 1986, some 2,000 students from 26 universities across South Korea took refuge inside five buildings at Konkuk University as part of a protest against military dictator Chun Doo-hwan.

Students holed up for three nights inside barricaded buildings as the authorities cut off power and water, pressing students to surrender. Thousands of riot police eventually stormed the campus.

Police wielded sticks, kicked and punched us as we were being taken to police buses, bound up like dried fish

“The campus turned into a battlefield at that time. Astonishingly, I saw similar scenes in Hong Kong these days,” said Hong Gye-sin, who was among the pro-democracy student activists. “Police wielded sticks, kicked and punched us as we were being taken to police buses, bound up like dried fish.”

Hong, now 55, was among the students who were arrested, but she was released without indictment as she did not play a leading role.

“It was a traumatic experience that still haunts me,” she said. “We were just powerless in the face of a brutal crackdown by police and this fact still makes me angry.”

A year later, waves of protests in South Korea eventually forced Chun’s government to accept a direct presidential election and other democratic reforms.

Chong from Nanyang Technological University said university campuses in other Asian countries were “highly politicised”, compared with Singapore’s.

When asked about the significance of Hong Kong university campuses becoming protest sites, he said it meant “you are dealing with intellectuals here and Beijing cannot say these are hoodlums, gangsters or troublemakers”.

The methods of Singapore’s old-guard leaders – including forcing parents to take control of their children – would not work in Hong Kong, Chong said, as there were wide-ranging societal grievances fuelling unhappiness in the city.

While the protests were sparked by the now-withdrawn extradition bill, those involved in the movement want other demands to be met, including an independent investigation into alleged police brutality. The campus occupation movement began on November 11 after a policeman shot a protester with a live round.

On how the late Lee Kuan Yew would have dealt with the current situation, Chong surmised that the former premier, whom critics say ruled with an iron fist, would have called for national dialogue. Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor has been meeting groups of Hongkongers in closed-door sessions.

“If parents, grandparents and pro-democracy legislators are quietly supporting the protests, protesters are not going to be terminated by the use of force,” Chong said. “You have to use the soft-power approach.” ■

Additional reporting by Park Chan-kyong