Mahathir, Anwar, the king: who are the key players in Malaysia’s political shake-up?

- Sultan Abdullah Sultan Ahmad Shah is interviewing every MP to ascertain which leader has majority support in the 222-member house

- All signs point to Mahathir, 94, retaining power under a brand new coalition but questions remain over his one-time arch rival Anwar’s future

Few countries do political roller-coaster rides like Malaysia.

Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad’s shock resignation and subsequent reappointment by the king as interim premier has intrigued citizens and global observers alike.

With all signs pointing to the 94-year-old Mahathir retaining power – with a strengthened hand – under a newly configured government, plaudits have been pouring in from observers who hailed his moves as a masterclass in brinkmanship. His career, which includes a 1981-2003 stint as the country’s leader, is chock-full of instances where he displayed similar guile, but this may be the most daring yet.

If as expected he is given a mandate to lead under a brand new coalition, Mahathir will be free of a major bugbear: a promise he made under the auspices of the now-defunct Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition to hand power to his one-time arch rival Anwar Ibrahim midway through the current electoral term.

The other lead personality of this saga is Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) leader Anwar. The on again, off again feud between Mahathir and Anwar has dominated politics in the country for the last two decades, and the million dollar question on the lips of Malaysia observers has remained the same through this period: will Anwar ever become prime minister?

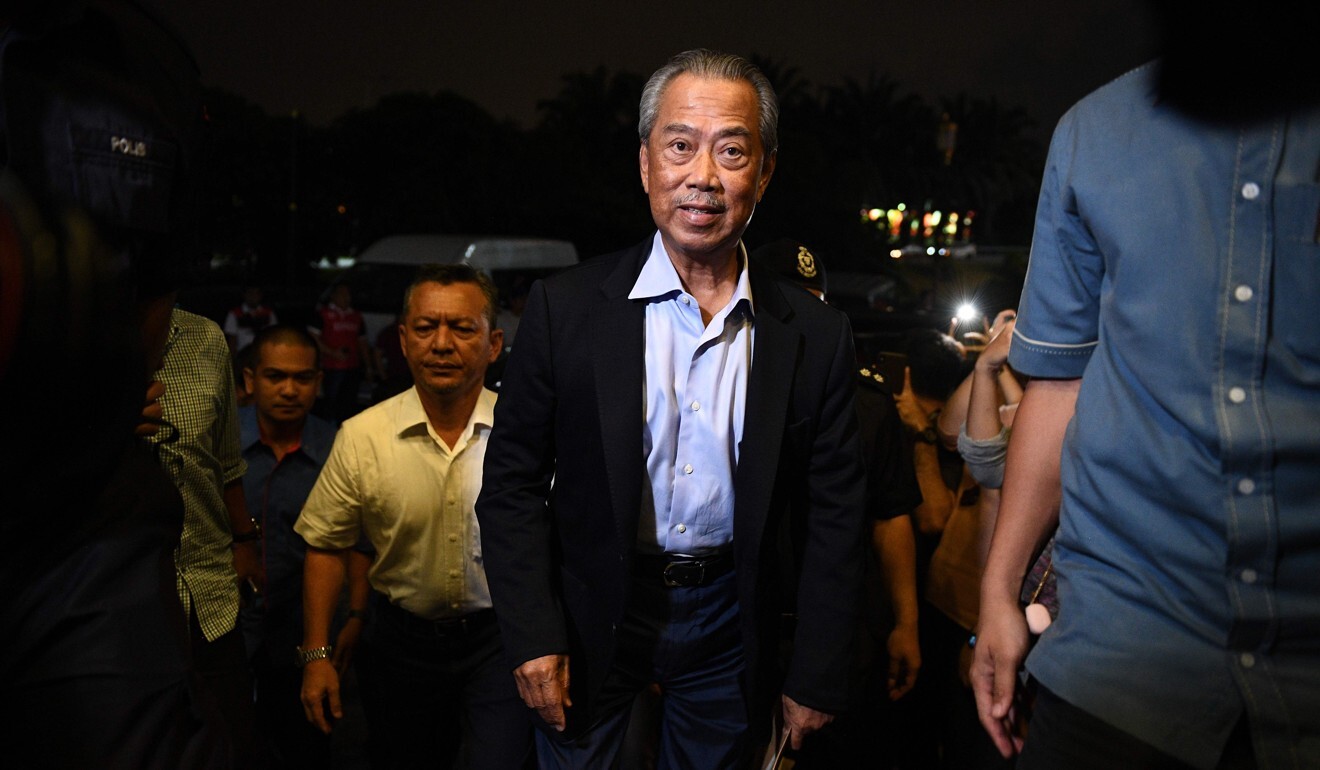

Also key in this drama is Azmin Ali, the ambitious economic affairs minister who stood by Anwar in his darkest days before warring with him. On Mahathir’s side of the coin there is Muhyiddin Yassin, a seasoned political warhorse who not only has weathered electoral duels but in recent years also stared down cancer. He has served as a “consigliere” figure for Mahathir and his predecessor Najib Razak, and may have a bigger role to play in time to come, say some well-connected political observers.

Above these party political players is the Yang di Pertuan Agong [He who is made Lord], Sultan Abdullah Sultan Ahmad Shah. As the reigning constitutional monarch, Sultan Abdullah will have the final say on how this saga pans out. He is currently in the midst of interviewing every MP to ascertain whether Mahathir or his alternative contenders have the support of a majority in the 222-seat parliament.

Here are the backstories of these five men.

MAHATHIR MOHAMAD, THE MASTER BRINKSMAN

Mahathir’s seven-decade political career is pockmarked with “do-or-die” moves, with the softly spoken but acerbic-tongued politician almost always triumphing. In most of these instances, the personalities at the receiving end of Mahathir’s political guile are people who had initially been close to him.

Among the most audacious of those acts was the open letter Mahathir penned as a budding politician in 1969, criticising the country’s founding prime minister Tunku Abdul Rahman. The letter triggered a chain of events that led to Tunku’s eventual ousting from power a year later. Mahathir paid a price as well as he spent time in the political wilderness for a few years after that.

Political duels were also aplenty when he took office as prime minister for the first time in 1981. The ruling party at the time, the United Malays National Organisation (Umno), was deeply splintered and Mahathir at one point governed with threadbare support from within the party.

In 1988, the party was deregistered for irregularities in an internal poll. Mahathir seized on the chance to form a new party, informally called Umno Baru (New Umno). The new party strengthened the incumbents’ grip on leadership positions but omitted Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah, who served as Mahathir’s finance minister for a period but who later became his most dangerous internal rival.

In more recent times, Mahathir was also responsible for the abrupt end to his immediate successor Abdullah Ahmad Badawi’s time in the prime minister’s seat. Mahathir campaigned for the removal of Abdullah after the latter balked at following through with major infrastructure projects the elder statesman had mooted during his earlier stint in power. The other high-profile victim is Abdullah’s successor Najib Razak. Also once a disciple of Mahathir, Najib was famously defeated by the 94-year-old in the 2018 elections after the statesman corralled support from one-time enemies to defeat the corruption-tainted premier and retake the hot seat he held for 22 years.

ANWAR IBRAHIM, THE ‘IRREPRESSIBLE OPTIMIST’

Anwar Ibrahim’s political career is deeply intertwined with Mahathir’s. He was plucked out of student activism by Mahathir, who later groomed the skilled orator and paved the way for him to rapidly rise to the deputy prime ministership. But their ties soured in the mid 1990s, and with rampant speculation that Anwar was seeking to oust him, Mahathir acted first and sacked him from the government in 1998. Anwar was subsequently jailed for sodomy and corruption – convictions international rights groups say were trumped up by the then-premier’s administration.

Despite his ordeals, Anwar branded himself an “irrepressible optimist” in a 2018 interview with the Post. That outlook on life was reflected in his comments in the midst of this week’s turmoil.

Asked by a reporter whether he was still poised to be the country’s next prime minister, the 72-year-old said wearing a wide smile on his face: “we shall see”. Under an agreement signed months before the general election in May 2018, Anwar was to take over from Mahathir after an interim period during which the older leader would help stabilise the country. Mahathir, however, has demurred on the actual handover date, one of the core reasons for the current crisis.

Anwar was in prison during the 2018 election but within a week of Mahathir leading the PH coalition to victory, Anwar was pardoned and released. He and Mahathir appeared to put their differences aside when they agreed upon a succession plan, which would ultimately lead to Anwar replacing Mahathir as prime minister. However, last weekend the Port Dickson MP accused “former friends and traitors” of seeking to undermine that agreement by ousting his party from the ruling coalition.

AZMIN ALI, ‘COUP MAKER’?

Azmin Ali, the Economic Affairs Minister in the just-dissolved cabinet, is widely believed to have been the chief executor of the now-failed political putsch aimed at alienating Anwar and his allies.

On Monday Anwar sacked the 55-year-old minister – his one-time protégé – and the younger politician’s close ally, the Housing and Local Government Minister Zuraida Kamaruddin, from the PKR. Nine other PKR MPs close to the sacked duo also resigned. Azmin was the party’s number two leader but has warred with Anwar for the better part of the last two years.

According to a person close to Azmin, the leader and his 10 allies left the party because they no longer could be part of a party “geared towards one’s man ambition to be prime minister at all costs”.

Ties between the two men soured only recently – pundits believe they grew distant because of Anwar’s belief that the younger leader was angling for the prime ministership that was originally promised to him. Just as Anwar had been under Mahathir’s pupillage before their relationship soured, Azmin served as Anwar’s personal secretary during the 1990s.

It was Mahathir – then serving as prime minister – who recommended that Azmin become Anwar’s personal secretary. Azmin stood by his boss when Mahathir sacked Anwar in 1998, even getting arrested for organising a pro-Anwar protest – and was instrumental in setting up PKR.

In 1999, he entered active politics and became an assemblyman for the state of Selangor. He would later go on to lead the state as chief minister in 2014, a year before Anwar was imprisoned for sodomy a second time.

Mahathir raised eyebrows in political circles when he named Azmin Minister of Economic Affairs after the 2018 polls – especially since the announcement was made after the younger politician reassumed his old job as chief minister. Azmin triumphed in a bruising battle for the PKR deputy presidency against Rafizi Ramli, an Anwar proxy, in late 2018.

The infighting turned ugly last year after a gay sex tape – purportedly showing Azmin with another man – was leaked to the media. People in Azmin’s camp privately said they believed Anwar was behind the move – an allegation the veteran politician denied strenuously.

MUHYIDDIN YASSIN, NOT A YES MAN

If there is someone who knows their way through Malaysia’s corridors of power, it has to be Muhyiddin. In total the 72-year-old has headed six ministries in a political career that began in 1978. He was the Home Minister in the Pakatan Harapan government. Before that, he held a higher office – serving as deputy to the ousted former premier Najib for six years.

Najib – currently on trial for his role in the multibillion-dollar 1MDB financial scandal – abruptly sacked Muhyiddin in 2015 after the latter questioned him over his role in the case. After he was removed from the ruling party, Muhyiddin joined forces with Mahathir and his son Mukhriz to form the Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia (PPBM). The party would later play an important role in the 2018 election outcome.

Where Muhyiddin lands after the current debacle is over is likely to be closely parsed. While few have put him as having prime ministerial ambitions, some people close to the Johor-born cleric’s son believe he has the chops to do the job if it lands on him.

Mahathir’s decision to quit PPBM – which is led by Muhyddin as president – this week has raised some questions about whether that indicates some kind of acrimony between the interim prime minister and Muhyiddin. People with knowledge of the matter say while there has been some occasional friction over some issues, the two remain allied with one another.

SULTAN ABDULLAH, ‘THE WISE KING’

All eyes are now on Sultan Abdullah, who has constitutional powers to determine which MP commands the confidence of a simple majority of the parliament to be appointed as prime minister. The 60-year-old in unprecedented fashion is conducting interviews with each lawmaker to ascertain who they back as prime minister and whether they would prefer a fresh general election.

Online, commentators raved about this approach and the king’s down-to-earth and calm behaviour even as he was thrust to adjudicate in one of the most serious political crises the country has witnessed.

The king treated journalists camped outside his palace to KFC meals on Monday, and the next day personally handed out packets of McDonald’s meals to the journalists. Videos showed him munching French fries as he chatted with the journalists.

“We are very concerned, yes I know. Be patient,” he said in brief comments to the media. “Let me do my duty. I hope we will find the best solution for the country.”

Sultan Abdullah last January was elected to serve a five-year term by eight other Malay monarchs in the country’s Conference of Rulers. Malaysia’s unique system of rotational constitutional monarchy requires the role of king, or Yang di Pertuan Agong, to be passed between the heads of the country’s nine royal households – the oldest of which dates to the 12th century. Royals remain widely revered in the country. Apart from their constitutional roles, the nine Malay rulers serve as guardians of the Islamic faith and centuries-old Malay culture.