Betrayal, treachery, ‘unrequited romance’: what next in Malaysian politics?

- Recriminations and charges of ‘traitor’ have been coming thick and fast from the camp of ousted prime minister Mahathir Mohamad

- His replacement Muhyiddin Yassin now faces a rocky road ahead as he seeks to quickly establish his government’s legitimacy amid formidable opposition

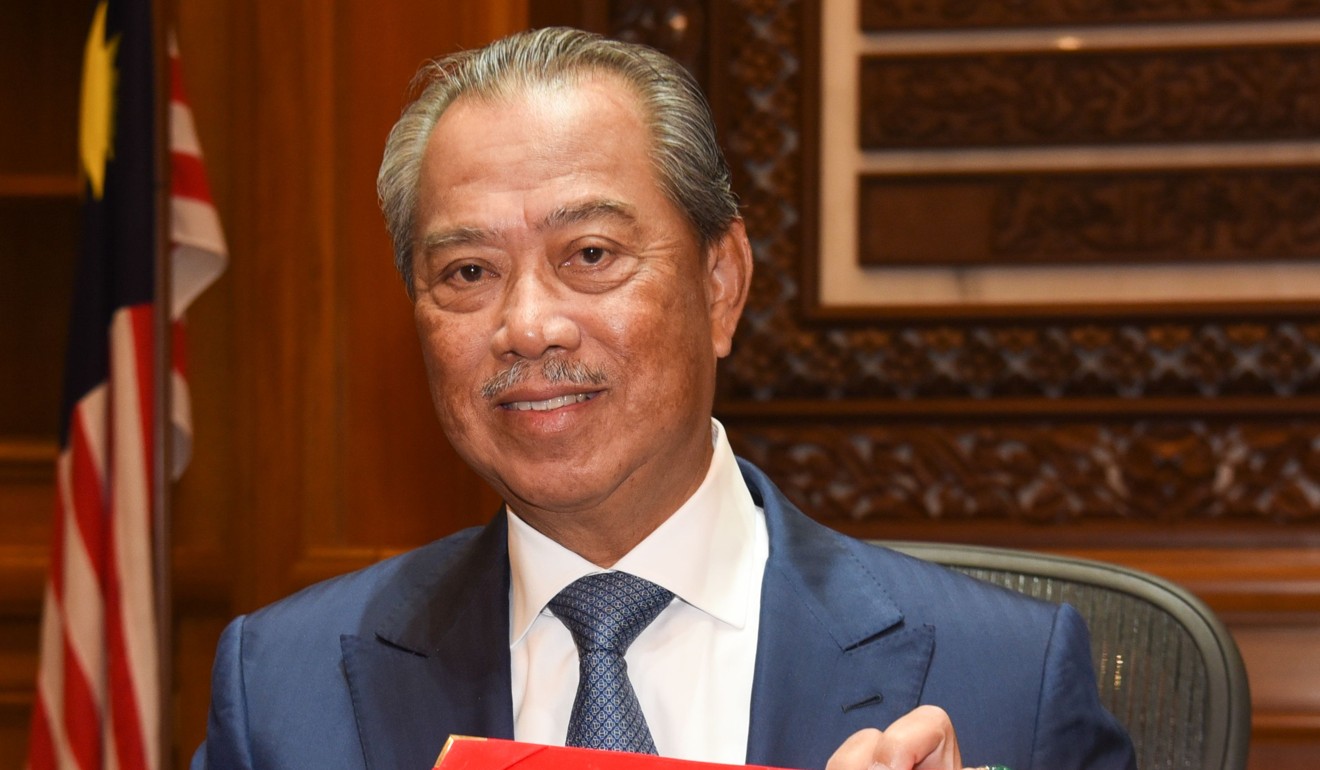

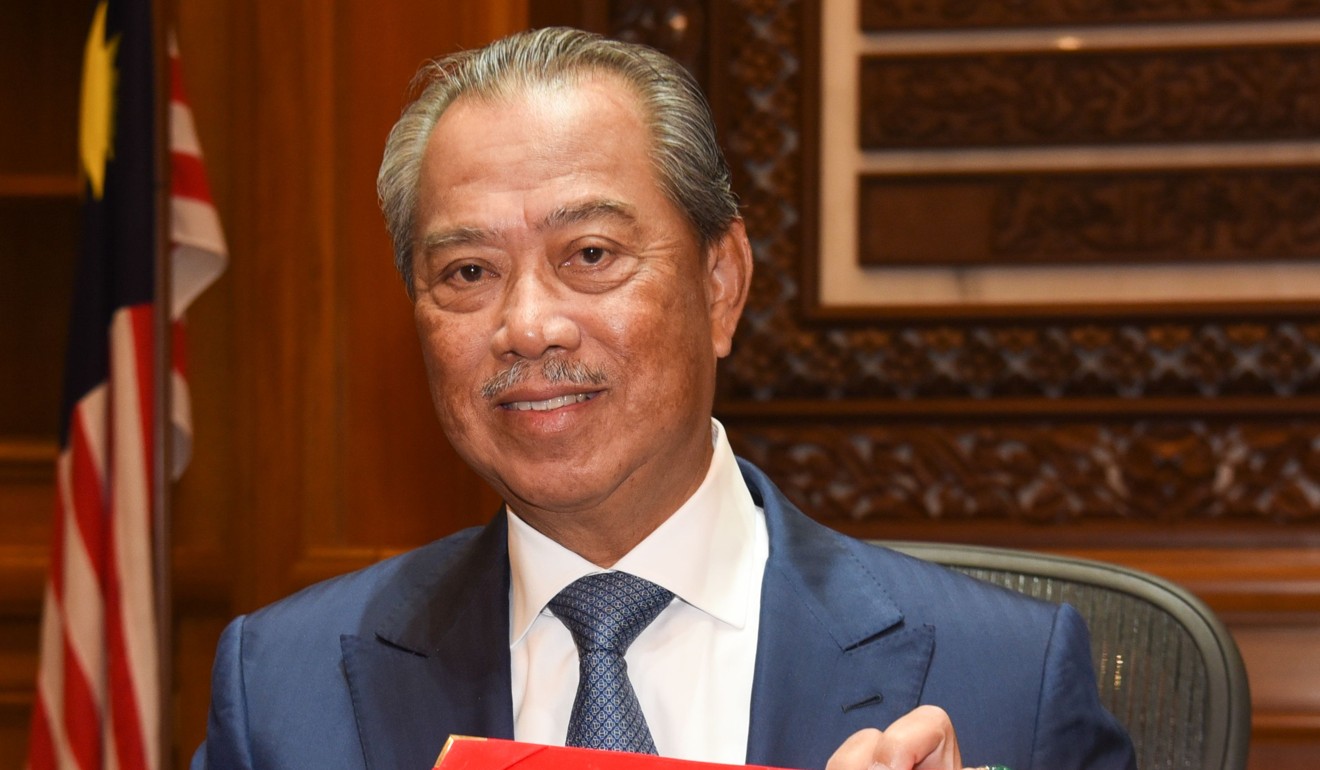

Speaking to Malaysia’s 32 million people for the first time as prime minister this week, Muhyiddin Yassin sought to press home a key message: the mantle of national leadership was thrust upon him, he had not actively set out to oust the country’s grand old man of politics.

The 72-year-old leader stressed that he accepted the royal directive for him to succeed Mahathir Mohamad only as a means to end the political storm engulfing the country.

“I did not covet the post... I know you are all angry with me. And as I expected, I’ve been called a traitor by certain people,” Muhyiddin said in a televised address on Tuesday, in which he spoke Malay. “I am not a traitor. I am here to save our country from any form of crisis.”

For some insiders, these comments directly addressing the accusations of treachery were the most noteworthy part of the 12-minute speech in which Muhyiddin – until now an under-the-radar political operator – also sought to outline his administrative credentials and promised to be a “prime minister for all Malaysians”.

A well-placed source who had a ringside seat to the political turmoil that began late last month said the newly minted leader’s remarks showed the “traitor” label was striking a raw nerve as he contemplates the rocky road ahead for his fledgling Perikatan Nasional (National Alliance) government.

Muhyiddin this week pushed back a parliamentary sitting that had been scheduled for March 9 by more than two months. Mahathir and his allies – who claim they and not Muhyiddin have the backing of the majority of parliament – have vowed to move a vote of no-confidence in the administration when lawmakers convene on May 18. If that happens, a snap election may be called.

“Muhyiddin could have ignored it [being labelled a traitor] and put the focus on his future plans. He already won the battle. But he knows it may stick, so he must push back,” said the insider, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

While the new prime minister was expected to be focused in the coming days on appointing ministers and getting on top of the twin crises facing the country – an economy wracked by global trade headwinds and the coronavirus epidemic – he could find himself spending an equal amount of bandwidth fighting off the portrait of betrayal being painted by his opponents, said the person.

Going by the multiple public accounts of Muhyiddin’s political coup being circulated by Mahathir’s camp, that may be a prescient observation. Alongside Muhyiddin, the former Economic Affairs Minister Azmin Ali and Mahathir’s one-time political secretary Muhammad Zahid Md Arip have emerged as the main Perikatan Nasional personalities being described as traitors.

The potency of the narrative is particularly strong because the person doing most of the accusing is Mahathir himself – upsetting the counter-spin by Muhyiddin’s camp that they had endeavoured to take over the government with the elder statesman’s blessing.

“I feel betrayed, mostly by Muhyiddin. He has been working on this for a long time and now he has succeeded,” Mahathir said at a press conference last Sunday timed to begin just before Muhyiddin’s swearing-in ceremony.

Power was wrested from Mahathir, his on-off ally Anwar Ibrahim, and their Pakatan Harapan alliance – victors of the historic 2018 general election – after Muhyiddin pulled the Bersatu party, which Mahathir founded, out of the four-party ruling bloc on February 24. With his party’s head honchos acting against his wishes, Mahathir resigned as prime minister.

Influential Pakatan Harapan members, including Muhyiddin, joined forces with a bipartisan caucus of predominantly Malay MPs to remake the administration, omitting the Chinese-centric Democratic Action Party (DAP) and sidelining Anwar, prime minister-in-waiting and standard bearer for the country’s promise of multiracial democracy.

Following days of political wrangling and horse trading, the constitutional monarch, King Sultan Abdullah Sultan Ahmad Shah, appointed Muhyiddin as prime minister after interviewing every MP and concluding the former home minister had the support of parliament.

“Traitor is a damaging label” for Muhyiddin’s government as it sought to quickly establish legitimacy amid formidable opposition led by Mahathir, said Hasan Jafri, founder and managing director of consulting firm HJ Advisory and a long-time observer of Malaysian politics.

“It may not hurt them so much when it comes to policies but it can hurt them in the court of public opinion and in any future elections,” he said.

BLINDSIDED

That logic appears to have been fully grasped by Mahathir and his Pakatan Harapan allies.

Betrayal, treachery and disappointment were key themes in the postmortems offered by the leaders this week of just how they were blindsided by the coup.

Fahmi Fadzil, spokesman for Anwar’s Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR), referred to Perikatan Nasional as “Pengkhianatan Nasional” (National Betrayal) on Twitter. In a video message to party members, Anwar was not as caustic but urged remaining cadres to stick to their principles. “We were given the opportunity to collude with the old groups who had destroyed our country. We chose to stick with our principles. Those who left us have betrayed our struggle,” he said.

Joining Muhyiddin on the political dartboard is Anwar’s estranged ally Azmin, who defected from PKR to Bersatu in the midst of the turmoil. He is widely seen as the main link between the defecting Bersatu party and its two new right-wing allies – the ethno-nationalist Umno and hardline Islamist PAS party.

Umno, or the United Malays National Organisation, was the dominant party in the Barisan Nasional bloc that ruled Malaysia for 61 uninterrupted years until the 2018 elections. A number of its leaders, including the former prime minister Najib Razak, are on trial for corruption.

“In the power grab, Azmin was the bridge to Umno, through his close connections to Hishammuddin Hussein,” said political analyst Bridget Welsh, referring to Najib’s cousin, an Umno grandee who is seen as among the front runners to be given a senior cabinet position by Muhyiddin.

“Azmin’s close alliance to members of Umno – and their goal of getting into power and getting off from charges – fostered distrust within Pakatan Harapan, and his actions in the power grab have provoked strong views of ‘betrayal’,” Welsh said.

Conversations with PKR insiders showed the anger towards the 55-year-old politician was palpable. The consensus view was that he was “bitter” about Anwar being handed the prospect of taking over from Mahathir midway through the current electoral term as part of a pre-election Pakatan Harapan pact.

Azmin last year angered the PKR when he called for Mahathir to disregard the promise and stay on for the full term.

“Azmin’s unrequited romance with PKR made him bitter since the day Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim made a comeback,” a senior party official told This Week in Asia .

Describing the nine loyalists who followed him to Bersatu as “his cartel”, the PKR leader said Azmin had ultimately made his political moves “at the expense of the rakyat (people)”.

Also slighted by Azmin’s actions were the DAP, whose mainly Chinese support he relied upon heavily when he was the chief minister of Selangor state from 2014 to 2018. His chief adviser Khalid Jaafar received a shot across the bows on Friday when he suggested in a tweet that Amanah, a Pakatan Harapan constituent party, had become a boneka (puppet) of the DAP. Hannah Yeoh of the DAP shot back: “Enjoy your new stint as the new Boneka Umno”.

Kadir Jasin, a Mahathir loyalist who sits on the Bersatu supreme council, identified the third personality who turned his back on the former prime minister when he was needed the most: ex-political secretary Muhammad Zahid Md Arip.

At a tempestuous meeting of Bersatu on February 23 – the day before Muhyiddin pulled the party from Pakatan Harapan – Kadir said Zahid surprisingly spoke in support of the split even though it was not Mahathir’s position. “It was as if the majority of the supreme council leaders were possessed by the devil as they pressed Dr Mahathir incessantly to agree with them in pulling Bersatu out of Pakatan Harapan and joining Umno and PAS,” Kadir wrote on Facebook.

“Those who defended Dr Mahathir were a minority and comprised Supreme Council members with no political ambitions … But there were also hypocrites and back-stabbers,” he said. “In front of Dr Mahathir, they would support [him] but [they] actually betrayed him.”

In the Perikatan Nasional camp, one insider sought to paint a scene of relative calm within the ranks even as cries of betrayal continued unabated from the opposite camp.

“This move ultimately is good for Malaysia. We put an end to the endless politicking, endless bickering, endless talk of succession. We have stability now and we will focus on the economy,” said the political operative.

From the outside, the view was less rosy. By press time, Muhyiddin had not named a cabinet and there was mounting speculation about differences between the prime minister’s Bersatu and Umno – which has more parliamentary seats – over which party should be allocated top portfolios.

By Friday, in the states of Penang and Selangor – the country’s two wealthiest regions – several Bersatu assemblymen had pledged allegiance to Mahathir, who continued to command significant support in the party despite his ousting as prime minister. And in the state of Melaka, Umno assemblymen said they were “cutting ties” with Bersatu despite federal-level cooperation between the parties.

“This crisis continues. I don’t know when it will end,” Mahathir wrote in his famous blog chedet.cc on Tuesday, 48 hours after Muhyiddin’s swearing-in. It appears the final chapter in Malaysia’s latest tale of betrayal is yet to be written. ■