01:29

South Korea’s ‘comfort women’ statues featuring PM Abe ‘lookalike’ spark anger in Japan

When Moon Jae-in gave his first speech marking the 1919 Korean uprising against Japanese colonial rule, the South Korean leader berated the former occupier for refusing to face up to its past.

During a 2018 ceremony to mark the 99th anniversary of the March 1 Independence Movement, Moon pointed to Japan’s territorial claim to Dokdo – a pair of tiny islets in the Sea of Japan – and its insistence that the issue of Korean women forced into wartime sexual slavery had been resolved as proof Tokyo had yet to “squarely face the truth of history and justice”.

“I hope Japan will be able to genuinely reconcile with its neighbours on which it inflicted suffering and walk the path of peaceful coexistence and prosperity together,” Moon said at the time.

This year, the president used the anniversary to look forwards instead, with an address that was conciliatory while also warning that ties between Seoul and Tokyo should not be held hostage to the past.

“The Korean government is always ready to sit down and have talks with the Japanese government,” Moon said on Monday, stressing the need for the neighbours to “concentrate more energy on future-oriented development while resolving issues of the past separately”.

“I am confident that if we put our heads together in the spirit of trying to understand each other’s perspectives, we will also be able to wisely resolve issues of the past,” he said.

01:29

South Korea’s ‘comfort women’ statues featuring PM Abe ‘lookalike’ spark anger in Japan

Experts say Moon’s outreach, after years of playing up tensions with Tokyo, reflects a changing calculus in Seoul as the South Korean leader faces a narrowing window to lock in gains from his inter-Korean peace efforts and a new US administration determined to buttress security cooperation between its allies.

Although often rocky, ties between the neighbours have been particularly strained since a 2018 South Korean court decision and a number of subsequent rulings found Tokyo and Japanese firms liable to compensate Korean former forced labourers and sex slaves. Japan has lambasted the rulings as “totally unacceptable”, arguing that all claims arising from its colonial rule were settled under a 1965 normalisation treaty and a 2015 compensation deal for surviving wartime sex slaves, euphemistically known as “comfort women”.

In 2019, Japan introduced restrictions on a wide range of exports to South Korea, a move Tokyo justified on national security grounds but which Seoul viewed as tied to their historical disputes.

In his March 1 address, Moon suggested the upcoming Tokyo Olympics could serve as a venue for diplomacy between countries, including the divided Koreas.

The president, who has a little over a year remaining in office, has made scant progress in his drive for Korean reconciliation since holding a flurry of summits with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un in 2018. The Winter Olympics in South Korea’s Pyeongchang that year coincided with a major thaw in inter-Korean relations, including an unprecedented visit to the South by Kim Yo-jong, Kim Jong-un’s influential younger sister.

“Ahead of the presidential election [in South Korea] next year, the ruling party wants to preserve the results and momentum of the Korean peninsula peace process and make political capital,” said Nam Chang-hee, a professor of international relations at Inha University in Incheon.

Moon is also expected to face renewed entreaties under the administration of President Joe Biden to embrace trilateral security involving Tokyo, a fellow US ally.

US secretary of state Antony Blinken has vowed to bolster security alliances that Washington views as key to countering China and North Korea, after its traditional partnerships in Asia were called into question under the Trump administration’s “America First” agenda. Blinken and US defence secretary Lloyd Austin plan to make their first trips to Japan and South Korea for talks with their allied counterparts later this month, Reuters reported on Thursday, citing multiple unnamed sources.

“There is not much room for South Korea and Japan to conflict with each other in front of the looming danger from the revisionist China to the status quo,” said Kwon Manhak, a professor at Kyung Hee College of International Studies in Seoul. “Second, the pressure to mend fences with Japan may have increased dramatically from the Biden administration, which will strengthen alliances and partnerships to counter China.”

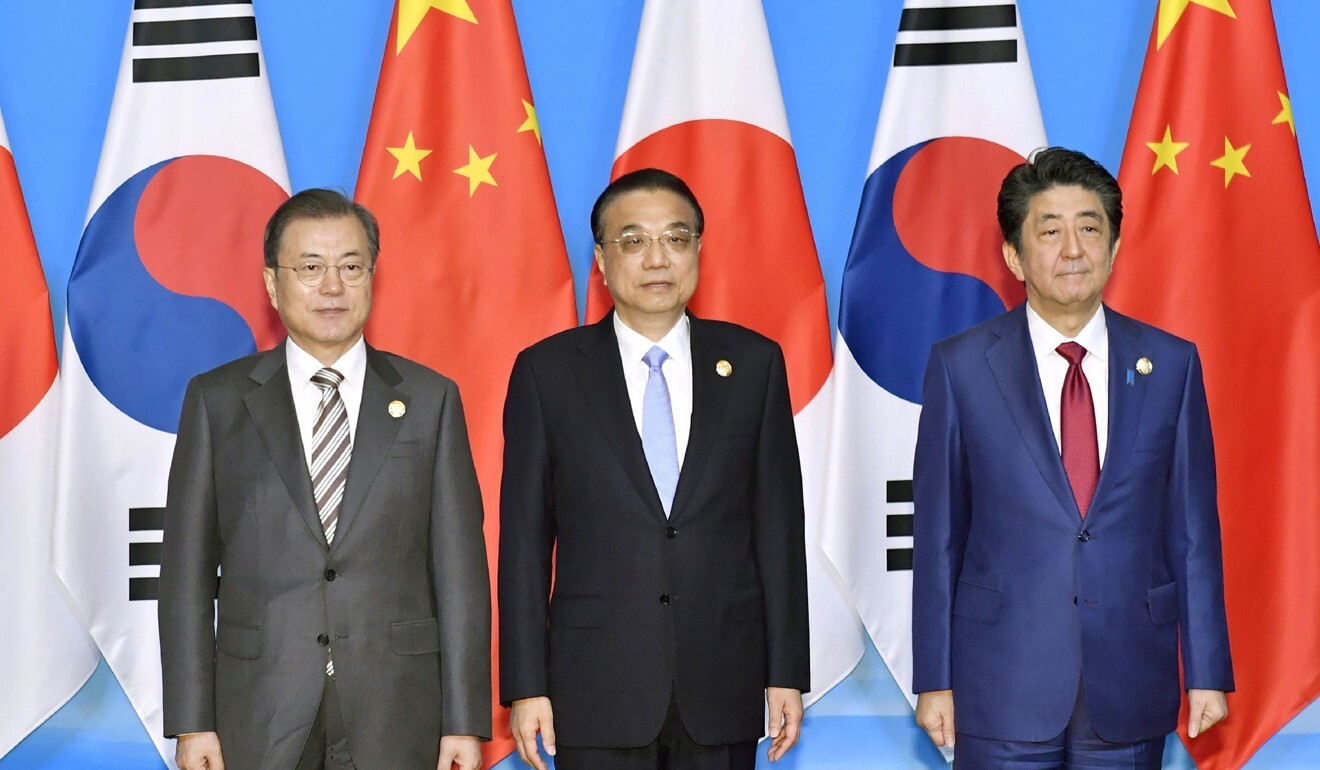

Kwon said closer South Korea-Japan ties would be anathema to China, which could try to drive a wedge between the sides and their relations with the US. Under Moon, Seoul has sought to forge closer ties with China, South Korea’s biggest trading partner, and Chinese President Xi Jinping has pledged to visit the country once pandemic conditions improve. On Friday, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang told the National People’s Congress that Beijing hoped to speed up free-trade negotiations with both South Korea and Japan.

“South Korea depends economically too much on China and therefore is very vulnerable to Chinese pressure and retaliation, as shown in the case of the THAAD deployment in South Korea,” Kwon said, referring to Beijing’s boycott of South Korean tourism that followed the deployment of the US missile defence system in 2017. “The Moon administration will have to deal with the crossfire between the two strategic players: either its economy might be taken hostage by China, or its security by the US.”

Nam Kijeong, a professor at the Institute for Japanese Studies at Seoul National University, said a bigger factor in South Korea’s shifting stance than Biden’s election was the appointment of Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga to replace Shinzo Abe, who was widely disliked in South Korea for his nationalistic views.

“The Suga cabinet hasn’t changed its fundamental stance, but it has adopted a willingness for dialogue,” Nam said. “This has had a big impact on South Korea’s efforts to hold talks.”

Leaders in Seoul have often rallied support by taking a tough stance against Japan, whose 1910-1945 rule over the Korean peninsula is a continuing source of bitterness and shame for many South Koreans to this day.

Moon railed against “pro-Japanese collaborators” throughout Korean history during his 2017 election campaign, and in 2019 scrapped an intelligence-sharing pact with Japan and oversaw military exercises in the waters surrounding Dokdo as he faced a raft of political controversies and declining popularity at home.

In 2012, then president Lee Myung-bak visited Dokdo – a first for a South Korean leader – as he grappled with rock-bottom approval ratings during the final months of his presidency, sparking protests from Tokyo.

In recent months, Moon has begun to soften his tone. After a South Korean court in January ordered Tokyo to pay compensation to 12 former comfort women, Moon said he was “a bit thrown” that the ruling had ignored the international law principle of state immunity and that it was undesirable for courts to seize and liquidate assets belonging to Japanese firms implicated in forced labour – a turnaround from earlier remarks that the country’s judicial independence must be respected.

Moon’s outreach efforts face uncertain prospects, however, following an initial cool response from Tokyo, which has insisted Seoul offer “concrete suggestions” for resolving their differences.

“It won’t be easy, but the signs of change have raised expectations,” Nam said. “The signs of change are themselves a change.”

He suggested it was up to Tokyo to make the next move. “The South Korea-Japan relationship has suffered its difficulties, but if you look at it according to international standards, it is a quite mature bilateral relationship. You can’t solve problems by submitting to the one-sided demands of somebody else.”

But Shin Kak-soo, a former South Korean ambassador to Japan, said the ball was in Seoul’s court.

“The Korean government should be bolder and more active in mustering consensus among the various stakeholders on how to resolve these two history-related issues,” he said. “Given the complexity of the matter, it would take unflinching efforts on the part of the government.”

Park Cheol-hee, a professor of Japanese politics at Seoul National University, said Tokyo could drop its trade restrictions and Seoul restore intelligence sharing to help build trust, but it would be “very hard to narrow the gap” between the sides.

“Distrust runs so deep between political elites in both societies, especially in Japan,” he said. “Public opinion in both countries is not necessarily favourable toward each other.”