US-China rivalry: is the pressure on for Asean countries to choose sides?

- While Southeast Asian nations have maintained a studied neutrality as Beijing and Washington clash over issues such as the South China Sea, experts say some alignment has already happened

- But as the interests of China and the US diverge, the window of opportunity to not officially take a side is narrowing

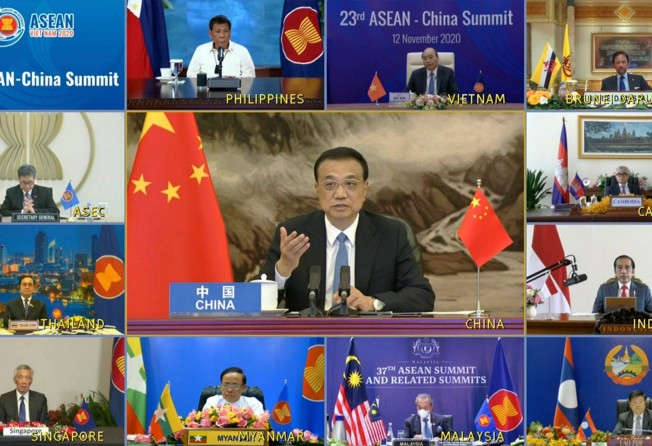

“Don’t force us to choose” has been a common refrain in Southeast Asia as Washington and Beijing clash over trade, technology and the South China Sea. But to political science professor Khong Yuen Foong, the 10 member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) have already largely aligned themselves with either China or the United States.

Khong, vice dean for research and development at Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, said at a recent webinar that Cambodia and Laos were clearly closer to China, having developed stronger political and economic ties with Beijing in recent years.

Vietnam and Singapore, on the other hand, had found “greater strategic comfort with the US”, he said, adding that countries such as Thailand, the Philippines and Malaysia had moved away from the US in recent years to become more embedded in the Chinese orbit.

Possibly the most neutral country, in Khong’s view, was Indonesia, which was “smack in the middle”.

“When these Asean countries say they do not want to choose, they are saying they do not want to move too far away from their current positions because they are comfortable with them,” he said. “Yet it is important to note that these positions are not cast in stone. They will shift over time, and in that sense, the political strategic alignments of the majority [of nations] in Southeast Asia are up for grabs.”

These positions, experts say, include a strategy of public hedging to keep their options open, as the countries’ economic and geopolitical considerations may vary.

Mark N. Katz, a government and politics professor at George Mason University in the US, said Southeast Asian states seeking close relations with China would not want to cut ties with the US either.

“Their friendlier ties to China may be their way of pressuring the US to either stop criticising them so much on human rights and democracy, or to get Washington to be more solicitous towards them,” Katz said.

Claiming not to take sides allows Asian countries to “have their cake and eat it too”, according to National University of Singapore political-science professor Chong Ja Ian, referring to the continuity of China’s economic opportunities and the strategic stability and predictability ensured by the US military presence in the region.

CHANGING CIRCUMSTANCES

Recent tensions in the South China Sea, however, have forced some countries to reconsider their positions.

Beijing has in recent weeks lined up Chinese vessels at the Whitsun Reef, which it claims despite the reef’s position within Manila’s exclusive economic zone. The Philippines says the vessels are maritime militia, and is facing domestic pressure to defend its sovereignty and protect its marine resources, but Beijing claims they are fishing boats taking shelter. China has also deployed aircraft carriers in the East and South China Seas.

Meanwhile, the US-China rivalry went up a notch last month when Washington and its allies such as Britain, Canada and the European Union imposed sanctions on Chinese officials accused of human rights abuses in Xinjiang. Beijing retaliated with sanctions on European lawmakers and institutions.

In the US Department of State’s 2020 human rights report, released on March 30, Washington for the first time classified Beijing’s actions in Xinjiang as “genocide and crimes against humanity”. On Tuesday, Washington said it was considering a joint boycott of the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, in coordination with its allies, amid calls from lawmakers and advocacy groups to back away from the games due to human rights violations in China.

The Philippines and even Malaysia, which have both built closer ties with China in recent years, would have hoped Beijing would have been more accommodating to them over the South China Sea dispute, George Mason University’s Katz said. “This hope having clearly proved unfounded, I actually see both moving more towards the US.”

Since Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte took power in 2016, he has chosen Chinese economic largesse by downplaying Manila’s arbitral victory that same year, when an international tribunal at The Hague rejected China’s “nine-dash line” claim to sovereignty over nearly the entire South China Sea. Though the Philippines is a strong security ally of the US, it is heavily reliant on Chinese Covid-19 vaccines.

Duterte’s position is a far cry from the preceding administration of Benigno Aquino III, who not only initiated the landmark arbitration case in 2013 but two years later also made a veiled comparison between China’s activities in the South China Sea and Nazi Germany’s expansionism before World War II.

Malaysia, which was friendly towards China during Najib Razak’s prime ministership from 2009 to 2018, found itself pulling back once he was ousted from power. The proposed East Coast Rail Link – part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative – agreed between Beijing and the Najib administration was scuttled, but was later revived under new terms and conditions.

On Laos and Cambodia, Katz said aligning with Beijing was less about the US-China rivalry and more to do with those countries’ continued fear of Vietnam, coupled with their realisation that Washington was unlikely to help them since it now was on relatively good terms with Hanoi.

Cambodia for centuries had a fraught relationship with Vietnam over the latter’s attempts to colonise it. In 1978, Vietnam’s invasion and decade-long occupation of Cambodia on the pretext of removing the murderous Khmer Rouge regime also left bitter memories among many Cambodians. Due to its dominance during the 19th century, Vietnam regards both Cambodia and Laos as vassal states.

“Small states like Laos and Cambodia are more concerned about their immediate neighbours than global geopolitics, but are willing to exploit a great power’s geopolitical concerns to get its help against their neighbour,” Katz said.

Kashish Parpiani, a strategic studies fellow at the Observer Research Foundation, a Delhi-based think tank, said even if countries such as Thailand and the Philippines forged closer ties with China, they would be keen to maintain their long-standing security ties with the US.

Thailand is a major non-Nato ally of the US – a designation given by Washington to countries that are not in the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation but have strategic working relationships with the US Armed Forces.

Manila, in particular, had become aware that unwinding its security ties with the US carried “the risk of only emboldening China”, Parpiani said. He added that the Philippines had in recent weeks reversed its decision to terminate the Visiting Forces Agreement, a 1998 agreement between Manila and Washington that provides the legal framework under which US forces can operate on a rotational basis in the country.

Speaking in his personal capacity, Paul J. Smith, a professor at the US Naval War College, said even though Vietnam shared a common interest with the US in balancing Chinese influence in the region, there were limits to how close both countries could get.

“At some point, the US will issue a report [on Vietnam’s] human rights or legal system that will rub Hanoi the wrong way, and then the ‘chill’ will be back in the relationship,” he said. “Vietnam doesn’t want to cut itself off completely from some of the fruits of the Chinese economy, so it will hedge.”

NARROWING WINDOW?

Analysts said it was possible that the window of opportunity for not taking sides was narrowing for Asian countries.

In the past, when there was greater convergence in US-China interests, countries “could find a spot somewhere in the overlapping policy space”, said Chong from the National University of Singapore.

“As Washington and Beijing diverge on their interests, this policy space shrinks and actions previously deemed acceptable and as ‘not choosing sides’ may now find a less hospitable environment,” he said. “At some point, some states may find it less costly and less risky to pick a side.”

Parpiani of the Observer Research Foundation said much would depend on whether US President Joe Biden’s administration continued confronting Beijing on multiple fronts. Among other things, the US is looking to further restrict sensitive technology exports to China and invest in innovation to reduce its dependence on Chinese tech.

Pointing to how the Trump administration had set up the Clean Network, comprising more than 60 countries, to establish common standards in digital governance, Parpiani said such initiatives guiding the acquisition and use of technology and services from China had begun to gradually force countries to pick sides.

“It now remains to be seen if Biden continues that push under his stated policy of rebuilding US alliances and confronting China with the cumulative strength of multilateralism,” he said.

Rohan Mukherjee, an assistant political science professor at Yale-NUS College in Singapore, said the main factor that might cause changes in alignments would be Beijing’s own behaviour in the region.

He added that countries currently trying to take a middle path were not guaranteed to pick the US if compelled. “Many countries in Southeast Asia would rather learn to live with Chinese hegemony than increase the likelihood of great-power conflict by expanding the US alliance system in their backyard.”