03:01

Protests grow to cancel Tokyo Olympics as Covid-19 outbreak worsens in Japan

Our Tokyo Trail series looks at key issues surrounding the 2020 Olympics, which are scheduled for late July.

The Olympics has, in the past, provided an informal setting for national leaders to meet, shake hands in front of the cameras, take in an event and then sit down to discuss issues of mutual concern. For South Korea and Japan, there were hopes as recently as this month that the Tokyo Games might be used to bridge some of the differences between the East Asian neighbours.

But with time running out before the July 23 opening ceremony in the Japanese capital, it appears increasingly unlikely that sports will on this occasion enable diplomacy – a development analysts say is unfortunate, but ultimately unsurprising.

“Any chance that leaders have to meet and talk that is not taken is a missed opportunity, especially if those talks had the potential to at least incrementally improve a relationship,” said Stephen Nagy, an associate professor of politics and international studies at Tokyo’s International Christian University.

“So yes, it is unfortunate that this chance appears to have been missed, but I also think this was always going to be the likely outcome. Seoul and Tokyo are just too far apart at the moment. The divisions across the spectrum – political, military, social, business – are just too deep.”

The list of grievances between the two neighbours is long and complicated, but largely revolves around Japan’s colonial rule of the Korean peninsula between 1910 and 1945.

03:01

Protests grow to cancel Tokyo Olympics as Covid-19 outbreak worsens in Japan

Key issues include South Koreans’ insistence that Japan pay compensation for “comfort women” who served in brothels for the Japanese military during the occupation, and forced labourers at Japanese companies. In the face of a series of recent court hearings, Tokyo insists that all claims for the colonial period were settled under the 1965 treaty that normalised post-war relations with Seoul.

The two nations are also at loggerheads over the sovereignty of South Korean-controlled islands halfway between the two neighbours.

Analysts point out, however, that previous Olympics have seen other countries overcome issues that appeared intractable – even if on a temporary basis.

Former United States president George W. Bush made a highly publicised visit to the 2008 Beijing Olympics, where he attended a number of events, and the US delegation was warmly welcomed by then premier Wen Jiabao. The two sides congratulated each other on their athletes’ performances and, for some years, the relationship between Beijing and Washington was noticeably warmer.

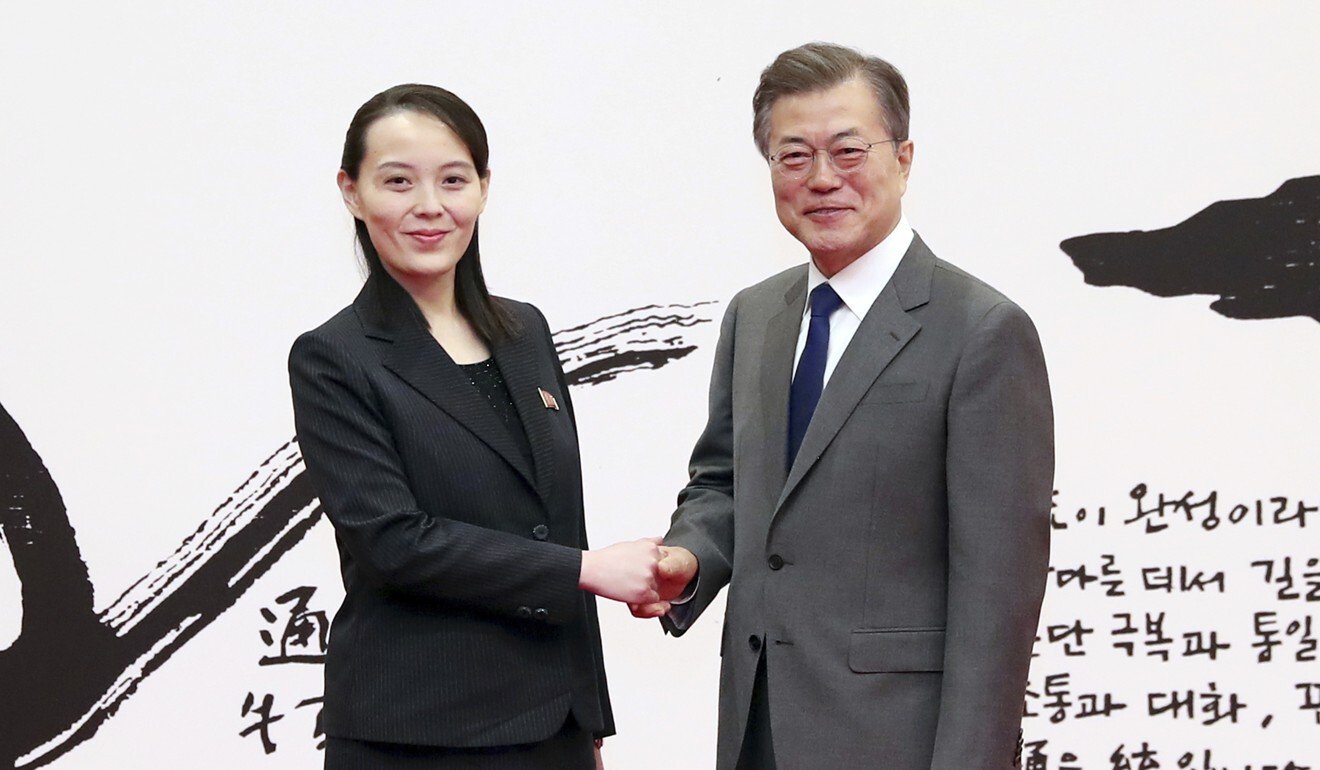

The potential of the Games to ease entrenched positions was illustrated even more dramatically when South Korea hosted the Pyeongchang 2018 Winter Olympics. Despite the bad blood that existed between North Korea on one side and the US and South Korea on the other, Pyongyang was convinced to field a united Korean women’s ice hockey team. Kim Yo-jong, the younger sister of North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, also headed a delegation that attended the Games and shook hands with South Korean President Moon Jae-in.

“What was particularly surprising about Pyeongchang was not that the North Koreans showed up, but the context of what had gone on so shortly before,” said Leif-Eric Easley, a professor of international studies at Ewha Womans University in Seoul.

“This was the time of ‘fire and fury,’ of the North working on its long-range ballistic missiles to deliver a nuclear warhead to the US, of firing missiles over Japan, of [then president Donald] Trump being quite assertive in his rhetoric and sending more forces to the region,” he said.

“The situation was very tense. So for it to switch so suddenly to engagement, for Kim to send his sister, that was a dramatic turn of events,” Easley said, adding that Moon was able to “leverage” that breakthrough to turn 2018 into “a year of summits” with Pyongyang.

But the likelihood of Seoul and Tokyo burying the hatchet are slim.

“Both sides feel snubbed or even betrayed by one another,” Easley said, explaining that bilateral bones of contention had been magnified in the context of the Olympics.

Tokyo has ignored a request to remove a speck that appears on the map of the Olympic torch’s route around the Japanese archipelago – the Korean-controlled Dokdo islets, which Japan claims and refers to as Takeshima. Adding to South Korean’s fury is the fact that Seoul acquiesced to a similar complaint by Tokyo ahead of the 2018 Winter Olympics to erase the islands from maps it drew up for the Games.

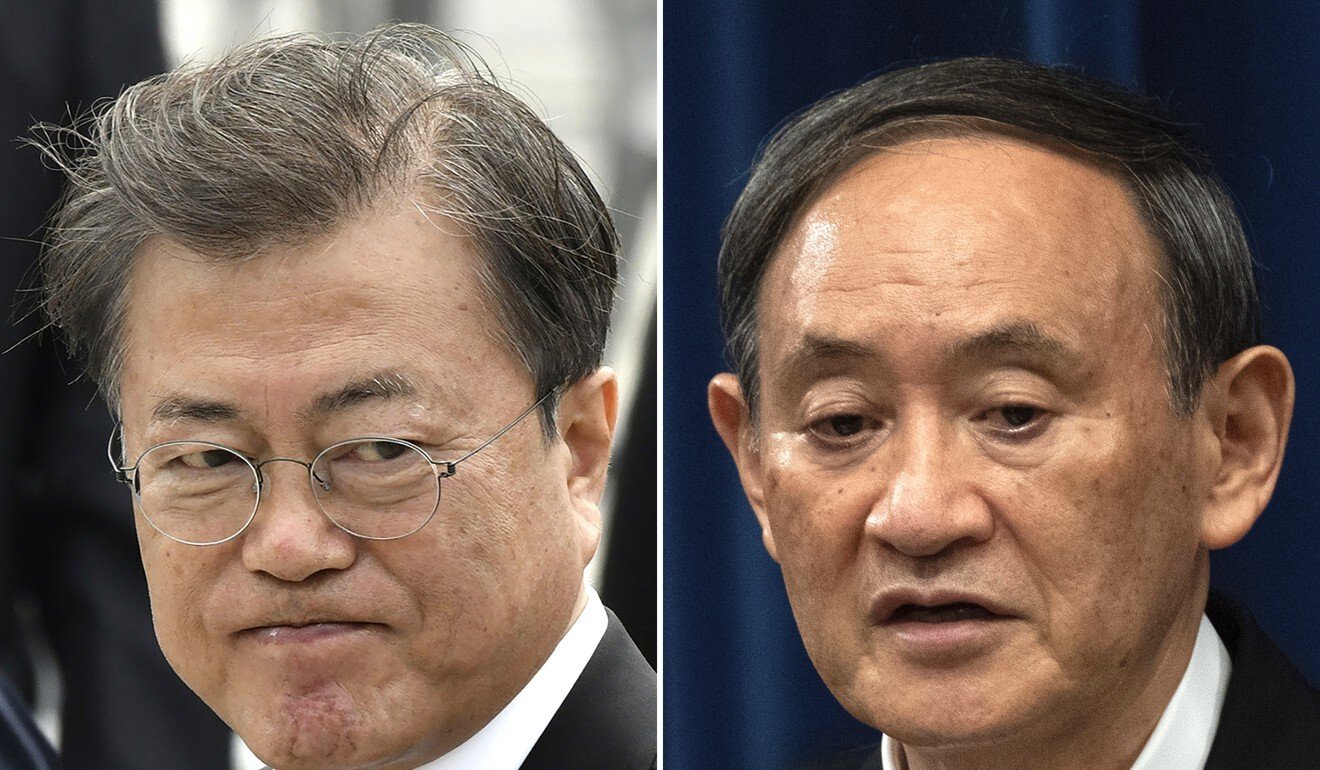

Several South Korean politicians have demanded that the government announce a boycott of the Olympics, though Seoul has thus far resisted. The ongoing legal cases involving comfort women and former forced labourers have also served to deepen anger in the country – as was the decision that Japan’s Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga did not have time to meet Moon during the recent G-7 meeting in Britain.

Though it appeared to be a last-minute development that Tokyo blamed on scheduling problems, many South Koreans perceived it as a deliberate slight and a further indication that Japan is not interested in negotiating on issues of shared concern.

Nagy from the International Christian University concurs. “The calculation is that Moon will be out of office soon and it is not worth investing in the relationship and helping him to install his protégé as the next South Korean president,” he said.

“Japan is hoping for a different government [when Moon’s term ends] next year, probably a more conservative administration, which would still have issues with Japan over history and territory but would do a far better job of siloing those concerns in order to prioritise security, trade, North Korea and other elements of the two-way relationship that they consider more pressing.”

Ewha Womans University’s Easley said there were other considerations for Suga, not least of which is the need to bring the Covid-19 pandemic under control in Japan before the Olympics starts.

“Suga is certainly preoccupied with the virus and how it will impact the Games, so it is understandable that he would focus on that rather than using the occasion as a diplomatic opening,” he said, pointing out that the Japanese leader also has to consider his popularity at home as he will need to contest a general election in the coming months.

There seems to be no end to the disagreements the two sides can embroil themselves in, often at the behest of minor pressure groups and encouraged by the media. The latest is an accusation from Seo Kyoung-duk, a professor of education at Sungshin Women’s University, who has accused Japan of claiming one of South Korea’s most famous athletes as one of its own.

According to Seo, a museum in Tokyo celebrating Japanese athletes claims that Sohn Kee-chung was Japanese when he set a new Olympic marathon record on his way to a gold medal in the event at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Korea was at the time part of the Japanese empire. Seo has sent a letter of protest to the Tokyo Olympics organising committee demanding that a new explanation be added to the museum display. “It is a historical fact that Sohn participated in the Japanese team with the Japanese flag on his chest, but the world should be properly informed of the fact that he is Korean, not Japanese,” he was quoted in The Korea Times as saying.

Hitting back in a Wednesday editorial, Japan’s conservative Sankei newspaper said changing the record of more than 80 years ago would be a “historical distortion, since South Korea did not even exist at that time”.

“Critics of Japan in South Korea have found a new issue with which to lambast Japan,” it added.