Britain and India want Gurkha women to fight in their armies. Nepal’s not so sure

- The coronavirus is only the latest problem to befall plans by both countries to enlist Nepali women into the elite regiments

- While some argue the policy could be an economic boost for Nepal and a victory for equality, the public is increasingly asking whether young Nepalis – whatever their gender – should be fighting other countries’ battles

The Gurkhas are known for being among the most feared fighting men in the British and Indian armies. And, if London and New Delhi have their way, they could soon be known for being the most fearsome fighting women too.

Both Britain and India had hoped that their long held ambitions to enlist Gurkha women in their militaries would finally bear fruit this year, but with little more than three months to go before the end of 2021 both countries face an uphill battle to hit that target.

With the coronavirus ravaging Nepal and the emergence of a new government led by Sher Bahadur Dueba of the Nepali Congress that is perceived to be against the move, both countries have had to shelve their plans, at least for now.

Some of the toughest opposition has come from the Nepali public. While some see the plans as a boost for both gender equality and the Nepalese economy, others argue the practice of sending off many of their best young people to fight for other countries is an anachronism that – after more than 200 years – should have been put to the sword long ago.

Not helping matters for Britain in particular are that images of Gurkha veterans going on a “fast-unto-death” hunger strike in London this August remain fresh in the mind. The 13-day protest by a contingent of ageing Gurkhas seeking pension equality with their British former brothers-in-arms captured the attention of the world’s media and will not have been a good recruitment advert for the British military. Cynics suggest this may explain why, after so many years of intransigence, London finally caved in and agreed to hold formal talks between the two governments and Gurkha veterans’ representatives in a process that will culminate in December.

Then there are the legal obstacles either Britain or India would face before being able to recruit Gurkha women. Some experts say that the 1947 treaty signed by Nepal, India and Britain that led to Gurkha men fighting for the two foreign governments would need to be amended to cover Gurkha women. And that would require the Nepalese government to come on side – something it has so far shown little sign of doing.

However, if such problems can be overcome, proponents of the policy say that it could help boost an economy where nearly one in five youth aged between 15 and 29 is unemployed.

As Gajendra Budhathoki, a Nepali veteran journalist in Kathmandu, points out: “Nepal’s GDP is US$37 billion and about a quarter of that – US$10 billion – is sent in remittances by Nepali youths working overseas.”

Official silence

While the Nepal government has long been officially tight-lipped on the matter, observers say its reticence to change the status quo has been in evidence for years.

The British first expressed an interest in enlisting Gurkha women in 2007, but its approaches did not go down well with Nepali elites for two reasons. First, Nepal had only recently emerged from a bloody internal war with Maoist insurgents and needed a break. Second, in a parallel to the hunger strike of this summer, the Gurkha Justice Campaign had just arrived in London, highlighting the country’s poor treatment of Gurkha veterans.

The campaign, which had the backing of actress Joanna Lumley whose father served with the 6th Gurkha Rifles, was partially successful and led in 2009 to all retired Gurkhas winning the right to live in the UK. It also won a change in the pension rules which gave serving Gurkhas equal rights to other UK service personnel, though it failed to win the same right for Gurkhas who retired before 1997 and it is this failure that this summer’s hunger strike was aimed at addressing.

The election of Nepal’s first female president Bidya Devi Bhandari in 2015 rekindled British hopes and when the British Army in 2018 opened all its roles to women it announced a plan to enlist 200 Gurkha women.

Since then the British ambassador to Nepal Nicola Pollitt has worked tirelessly on the policy and, apparently not to be outdone by the British, the Indian Army Chief General MM Naravane has also pursued the matter.

Early in 2021, Britain again announced its intent to form a regiment of Gurkha women and in June India made a similar statement.

Since then, however, things have once again gone rather quiet. Emailed enquiries from This Week in Asia sent to the British Embassy, the Indian Embassy in Kathmandu, and Nepal’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs all went unanswered.

Hot potato for public

The lack of progress is likely due to how controversial the matter has proved to the Nepali public.

At issue, for most, is not the idea of gender equality.

As Gyanraj Rai, a Gurkha veteran, put it: “We have gender equality and fairness. Since we Gurkhas have been serving the British Army for so long, I don’t see why Gurkha women cannot join them.”

Ganesh Gurung, a former member of the National Planning Commission and a migration expert, thought the policy could empower women “not only financially, but psychologically”, even suggesting it could help bring about a fall in domestic violence against women.

Rather, the problem is that many people believe neither men nor women should be risking their lives to fight other countries’ wars.

“As long as the Nepalese state continues to send out soldiers to join the militaries of other countries, there should be gender equality, and women should have as much a right as men to sign up,” said the author Kanak Mani Dixit. “But on the broader front, we look forward to the day of Nepal’s internal prosperity when this practice will end, and neither women nor men will have to fight for a country other than their own.”

That view was echoed by the Nepali author and politician Jhalak Subedi, who said it was “a good thing” for Gurkha women to have the same right as the men to join either the British or Indian armies, but that ideally the entire policy of Gurkhas serving other countries should be reviewed and stopped.

Others are of the mindset that fighting – especially for a foreign country – should remain a man’s job.

Lalit Chandra Dewan, a retired major with 32 years of service, said Gurkha women should not be allowed to fight in wars.

“Any employment anywhere with decent remuneration for honest work is God-sent,” he said. “But if it is to bear weapons, like we did in our time, to fight other nations’ wars it is a big NO!”

Ties of history

Despite growing calls from the public to rethink the treaty governing Gurkhas’ service, Nepali politicians may be reticent to undermine a policy that has underpinned the country’s relationships with both Britain and India for so many decades.

The Gurkhas’ involvement with the British harks back to the Anglo-Gurkha War of 1814-1816. The Gurkha Kingdom (the name ‘Gurkha’ comes from the hill town of Gorkha from which the Nepalese kingdom expanded) was at the time one of the regional powers in South Asia. After being outnumbered and outgunned by the invading British, the Gurkhas signed a humiliating treaty that allowed them to join the British side and fight for them.

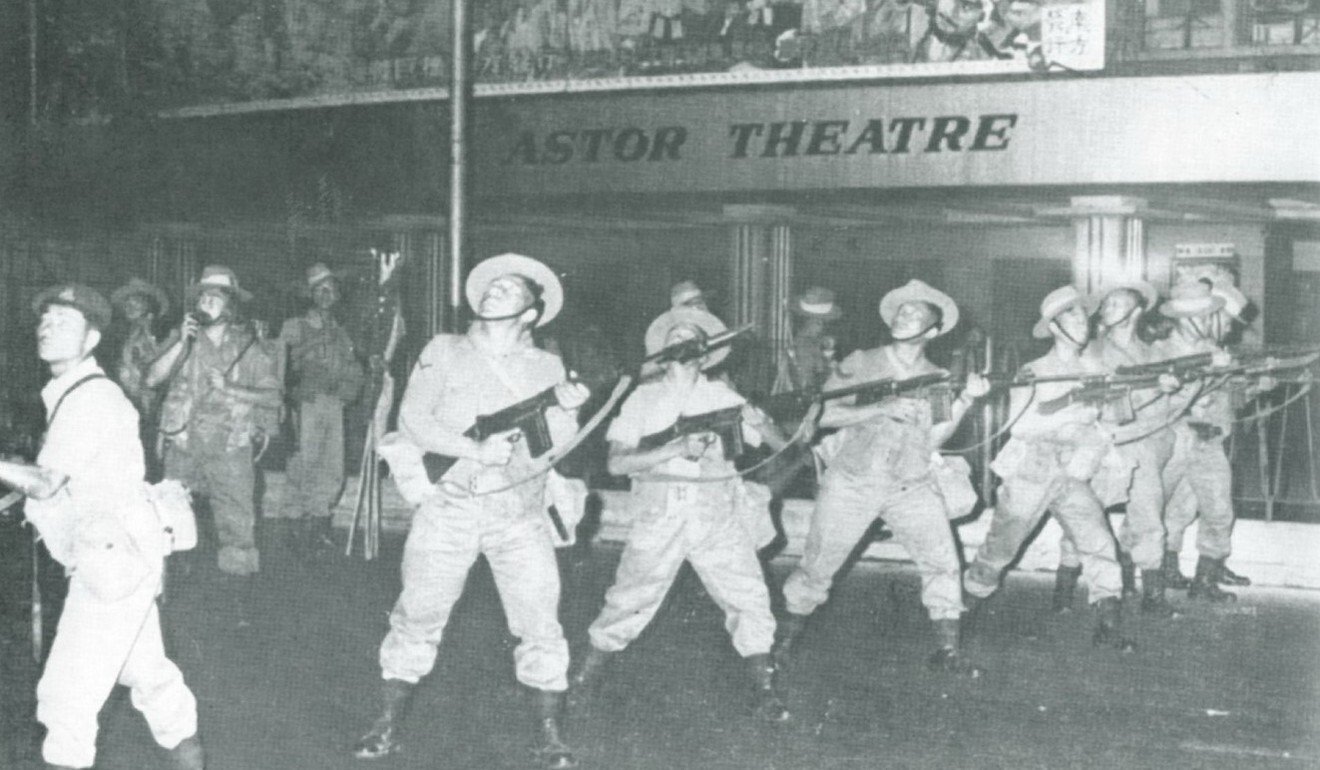

The main motive behind that policy was to take the sting out of Nepal’s military power by enlisting their best men in what was then the British Indian army. Few then might have foreseen that more than 200 years later and the Gurkhas would have fought alongside the British in two world wars, and served in Hong Kong, the Falklands, Iraq and Afghanistan and received 13 Victoria Crosses – the highest honour in the British army.

After India’s independence in 1947, the British and Indian armies split the Gurkhas between them. Under the Tripartite Treaty signed that year, four Gurkha regiments followed the British to Malaysia and Singapore while the remaining six Gurkha regiments joined the newly formed Indian Army. The British Army currently has a little over 3,500 Gurkhas in their ranks, while more than 100,000 serve in the Indian army.

Even without the issue of whether women should be allowed to serve, many observers argue that 74-year-old treaty is already long out of date and in need of review.

“The Tripartite Treaty of 1947 belongs to a past era, the situation now is completely different,” said the Nepali member of parliament Deepak Prakash Bhatt, who said the agreement should be scrapped and chastised the government for not taking “any position or stand” on the matter.

“The Nepal government must start negotiating with the British and Indian governments, and the formation of the negotiation team must comprise of the parliament, ministry of foreign affairs, ex-Gurkhas, historians and international law experts,” he said.

Hope dies hard

Despite the obstacles to enlisting Gurkha women, there are still many in the British and Indian establishments who believe the cause is worth fighting for.

“Gurkha females would have a huge amount to offer in the British Army, which already has a strong record of gender equality,” said Craig Lawrence, a former director of joint warfare in the British Army who served and commanded Gurkha regiments in Hong Kong, Africa, and the Balkans.

“As I understand it, the British Army has no objection to Gurkha soldiers, but for this to happen, the Nepalese government would need to agree to it.”

Atul K Thakur, an Indian columnist and policy analyst, went further, saying the recruitment of Gurkha women could help strengthen India’s bilateral relationship with Nepal.

“Considering the fast-changing geostrategic and geoeconomics fundamentals in the South Asian region, such trust in cooperation could reassure both sides of India’s commitment to deeper collaboration with Nepal and create a much-needed synergy,” he said.

Then there are those who point out that the idea of enlisting Gurkha women is not without prededent. In the 1960s a small number were recruited as nurses.

Tikendrada Dewan, a retired major and chairman of the British Gurkha Welfare Society, and a Gurkha campaigner, said Nepali women had excelled in the Queen Alexandra’s Royal Army Nursing Corps, where many were commissioned as officers.

“As chairman of the British Gurkha Welfare Society, I took up the issue of Nepali women with the British Ministry of Defence. Those aspiring to join the British Army should be given equal opportunity lest they be deprived while dependents of Gurkhas and those with BN(O) [British National (Overseas)] passports are enjoying this right. They are equal with our men in every aspect,” he said.

Rukmani Dewan O’Connor, a retired captain in the nursing corps, said she was proud to be one of the first Gurkha women to have served the British crown and felt honoured to have helped Gurkha families during her time both in Britain and in Hong Kong.

She said she hoped her service would inspire younger generations of women, whether or not they served in their own Gurkha regiment.