South China Sea: will Aukus affect Asean’s code of conduct talks with Beijing?

- China is eyeing gains in its negotiations with Asean for a code of behaviour in the resource-rich waters, as President Xi Jinping meets bloc leaders on Monday

- Beijing’s assertive tactics in the disputed waters, the Aukus alliance and Cambodia’s chairing of Asean are factors that will shape the meeting outcome, analysts say

Two years since the negotiations for a code of conduct in the contested South China Sea hit a roadblock, Beijing is keen for talks to progress as Chinese President Xi Jinping meets leaders of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) on Monday for a special China-Asean summit.

For decades, the claims by China, Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam have remained unresolved, and attempts between Beijing and the Asean bloc to draft a framework for rules and standards in the resource-rich waters have not borne fruit.

At a meeting last weekend between Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and Asean diplomatic envoys, Wang said both China and the bloc should advance consultations on the issue.

But as the leaders gear up for a fresh round of talks, changes in the regional security landscape over the past couple of years may have an impact on how Asean nations approach the discussions this time, analysts say.

Aristyo Rizka Darmawan, an international law lecturer at the University of Indonesia, said Indonesia was likely to raise the issue of illegal surveillance due to the presence of Chinese survey ship Haiyang Dizhi 10 in Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) bordering the South China Sea in recent weeks.

“I think it will also happen for other claimants,” Darmawan said. “Current issues that happened in the last few months might add [talking] points to the negotiation.”

The Philippines, for example, has issued a volley of protests against Chinese activities in the disputed waters this year, with the foreign ministry saying last month that more than 70 per cent of South China Sea-related protests in the last five years were filed this year. Malaysia has also summoned the Chinese envoy in Kuala Lumpur twice this year to protest the presence of Chinese ships in its exclusive economic zone.

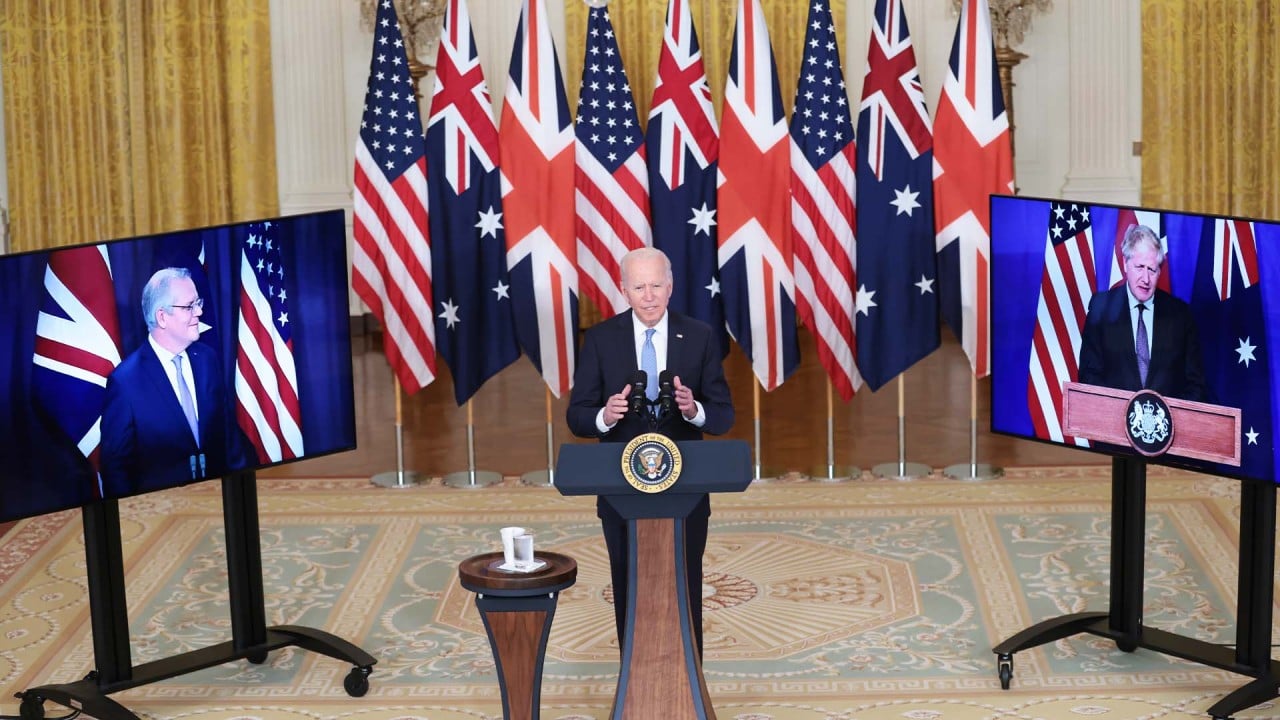

The most recent and significant development in the region is the creation of Aukus, the security pact between Australia, Britain and the United States that includes an agreement to help Canberra secure a fleet of nuclear-powered submarines and is widely viewed as a coalition to counter China.

Observers say the alliance is likely to increase geopolitical tensions in the region, which may in turn form another obstacle in discussions between Asean and China.

As Darmawan noted, Aukus is likely to push China “to expedite the negotiation of the code of conduct before the US has more influence in the region”.

A new complication

In July 2019, China and Asean completed a first reading of the code’s draft negotiating text, but due to the Covid-19 pandemic and the various stand-offs between China and Southeast Asian countries, there has been little progress since, Darmawan said.

In the meantime, Beijing’s militarisation of the South China Sea has grown – such as the building of military outposts, and the stepping up of patrols and incursions into claimant countries’ EEZs – while major powers including Australia, Japan, the US and a handful of European countries have conducted highly-publicised naval and navigation operations in the region.

In July, Britain’s Carrier Strike Group, led by the aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth sailed through the South China Sea, prompting Beijing to accuse London of “still living in its colonial days”.

This week, Japanese and US fleets conducted a first-ever anti-submarine warfare exercise in the contested waterways, according to the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force on Tuesday.

Charles Dunst, adjunct fellow with the Southeast Asia Programme at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said the Aukus pact would further complicate the code-of-conduct discussions as it reflected the US’ commitment to pushing back against China’s influence in the Indo-Pacific region.

“Aukus will serve to harden Beijing’s opposition to signing a code of conduct that constrains China in any way,” Dunst said, adding that the pact could prompt Beijing to “double down on its recent aggressiveness”.

Chester Cabalza, the founder of the Manila-based International Development and Security Cooperation think tank, said that with the launch of Aukus, China was likely to step up efforts in militarising the South China Sea and even intimidate claimant states.

“This will lead to a slower and uncertain path of the code of conduct [that is] intended to be completed next year,” said Cabalza, who is also a fellow at the National Defence University in Beijing. He was referring to China’s target set in November 2018 to reach an agreement on the code of conduct with Asean within three years.

Collin Koh, a research fellow at Singapore’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, said that according to the original single draft negotiating text adopted in June 2018, China had proposed a de facto mechanism for it to allow and disallow foreign militaries from conducting joint training exercises with Asean member states.

“That proposal was seen as running counter to the Asean member states’ sovereign autonomy and freedom to conduct such activities, hence it was pushed back,” Koh said, adding that Aukus was unlikely to change that dynamic.

Koh noted that Indonesia and Malaysia, which were vocal in flagging their concerns about the trilateral pact, had continued to maintain their respective defence and security partnerships with the Aukus members, especially the US and Australia.

“Hence, from this standpoint, I don’t believe Aukus will alter the issue of extraregional military activities in the South China Sea,” Koh said, adding that it was unlikely that Aukus would significantly shape code-of-conduct negotiations.

“Discussions remain stuck on the original sticking points, such as geographical coverage, the duties of signatories and non-signatories,” he added.

Koh said Asean states did not want to complicate the talks by including Aukus.

“This may lead everyone down the rabbit hole of more complicated and complex issues involving other groupings, such as the Quad, and broader issues regarding the Asean-centric regional security architecture,” Koh said, referring to the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue alliance between the US, India, Japan and Australia, which has become increasingly active in recent months.

Oh Ei Sun, a Malaysian political analyst and a senior fellow at Singapore’s Institute of International Affairs, said code-of-conduct talks had stalled as they had moved into the more sensitive issues relating to a robust and rigorous enforcement mechanism that would mean “some degree of surrender of sovereignty”.

“[However], prospective member states are almost all jealously defensive of their respective sovereignties, lest some sacrifice more than the other without commensurate rewards,” Oh said.

Cambodia as chair

Dunst of the CSIS said he believed a code of conduct was unlikely to be reached any time soon, pointing to how Cambodia – “the most pro-China country in Asean” – had previously blocked statements critical of China’s behaviour in the South China Sea.

“Phnom Penh is now chairing the bloc, making it only more difficult to imagine the two sides finalising a code of conduct this year,” Dunst said.

When Cambodia last chaired Asean in 2012, the regional grouping failed to issue a joint statement for the first time, as Phnom Penh did not accept the language criticising Beijing’s assertiveness in the South China Sea.

Since then, Cambodia has drawn even closer to China and has repeatedly blocked Asean statements that are critical of its larger neighbour, whom it relies on economically.

The differences could deepen should Aukus become more involved in the Indo-Pacific region

A new complication also emerged last week, according to Reuters, which quoted diplomatic sources saying that Asean nations had firmly opposed a Chinese envoy’s bid to let Myanmar’s military ruler Min Aung Hlaing attend Monday’s meeting.

The bloc made an unprecedented move last month to exclude a national leader from its biannual meetings by blocking the architect of February’s coup from attending. Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and the Philippines are believed to have actively pushed for Min Aung Hlaing’s exclusion, with the backing of the bloc’s current chair, Brunei.

Ryo Hinata-Yamaguchi, project assistant professor at the Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology at the University of Tokyo, said the progress of the talks would depend on what happens with Aukus and the reaction to those developments by Asean states.

While Aukus is primarily a trilateral defence alliance that also allows Australia to have nuclear-powered submarines by 2040, the US sees the pact as paving the way for more security agreements with its partners in the Indo-Pacific.

Washington has expressed interest in adding South Korea to its Five Eyes intelligence alliance – which also includes Australia, Britain, Canada and New Zealand – and earlier this year renewed a military pact with the Philippines that allows US troops to be stationed in the country.

“The differences could deepen should Aukus become more involved in the Indo-Pacific region, [and] this would lead to fault lines within Asean on geopolitical issues,” Hinata-Yamaguchi said.

This would also lead to greater dilemmas for states that have worked with the US as they would fear harsh reactions from China, he added.

“At the same time, should China’s reactions be too harsh, some states could also work closer with the US and its allies,” Hinata-Yamaguchi said.