China’s Southeast Asia embassies use local media to tell positive stories, undermine Western narratives: report

- ‘Tell China’s Story Well: Chinese Embassies’ Media Outreach’ report says China thinks the West is driven by a Cold War mentality

- Author Wang Zheng says Beijing’s efforts to forge ‘national positive image’ have seen mixed response; social media crucial, says analyst

Chinese embassies in Southeast Asia have been using local media to tell a positive “China’s story” in the region, with a core theme of the messaging being Beijing’s denunciation of Western narratives about its domestic politics and foreign policies, according to a recent report.

China regards these narratives as driven by a “Cold War mentality” where Western countries are motivated to demonise its achievements and sabotage solidarity among Asian countries with the ultimate aim of containing its peaceful development, wrote Wang Zheng, author of “Tell China’s Story Well: Chinese Embassies’ Media Outreach in Southeast Asian Media”.

The report is published by the Singapore-based ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

To refute Western narratives of it, China contends it firmly champions multilateralism, free trade, and a rules-based international order as enshrined in the United Nations (UN) charter.

To get its message across, it uses three channels – media events organised by its embassies; signed articles by Chinese leaders and diplomats in local newspapers; and interviews and media briefings by Chinese ambassadors with local media, wrote Wang, a former visiting fellow at the institute.

He is currently doing a PhD in political science in the US.

China’s efforts to forge a “national positive image” among Southeast Asians have received a mixed response. At the regional level, wrote Wang, views regarding China’s influence in Southeast Asia appear to be “more critical than what China may have expected”.

According to the 2022 State of Southeast Asia annual survey, foreign policy elites remain wary of Beijing’s growing influence in the region, although they recognise China as the most influential economic and political power there.

Only 7 per cent of respondents think China is a benign and benevolent power, while 58.1 per cent are not confident that China would “do the right thing” in global affairs, said Wang’s report.

“Contentious issues downplayed in ‘China’s story’, including China’s assertive stance on the South China Sea, its use of economic tools for political purposes, and its growing influence over Chinese diasporas in Southeast Asia, are among respondents’ top concerns over China’s engagement with the region,” he wrote.

In mainland Southeast Asia, the share of respondents receptive to China’s influence in the region is higher in Cambodia and Laos than in Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam.

“Among maritime Southeast Asian states, foreign policy elites in Brunei ... and Indonesia are becoming more amenable to Chinese influence than those in Singapore and the Philippines,” said Wang.

In Indonesia, where China accounted for around 10 per cent of the total foreign direct investment between January and September 2021, making it the third-largest contributor, the messaging of Beijing’s embassy has fallen short.

Ardhitya Eduard Yeremia, a lecturer in international relations at the University of Indonesia, said the Chinese embassy in Jakarta mainly uses mainstream media to get its message across.

“My argument is, who reads mainstream media these days? Not many and so the impact … is very, very low,” he said.

All negative stories about China in Indonesia come from social media, added Yeremia. “China has to deal with the challenges emerging in social media. This anti-China strategy (using social media) has been really effective.”

He cited the example of a “massive influx of Chinese workers in Indonesia” which has caused resentment among local people as they feel jobs are being taken from them. The news first appeared on social media.

“Those who mobilise anti-China sentiment using social media can reach hundreds of thousands of readers in just one day,” said Yeremia, noting that the Chinese embassy strategy does not match up to the challenges and more attention should be paid to the online world.

China’s narrative

Since President Xi Jinping took office in 2012, China has attached great importance to the notion of “discourse power” in its foreign policy agenda.

His speech at the National Propaganda and Ideology Work Conference in 2013 underscored the need to “tell China’s story well, disseminate China’s voice well, and strengthen China’s discourse power internationally”.

In Southeast Asia, China has been rebutting multiple Western narratives including the origin of Covid-19, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and South China Sea disputes, wrote Wang from the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

He said China counters criticisms of the BRI being a “debt trap” with the claim that it pursues a market-oriented approach to “foster a transparent, friendly, non-discriminatory and foreseeable financing environment” and alleviate the debt burdens of recipient countries.

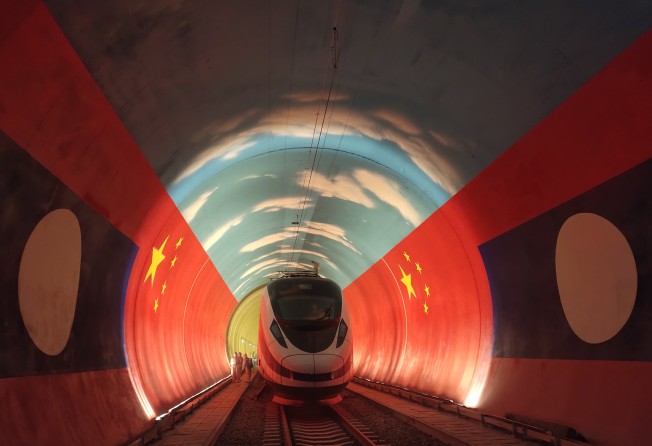

China also asserts in its messaging that BRI projects can promote economic growth and create job opportunities for recipient countries in Southeast Asia, wrote Wang.

On South China Sea disputes, he went on, China insists that the so-called “accusation” of its militarisation of the South China Sea is a vivid example of how Western countries “interfere in China’s internal affairs and drive a wedge between China and regional countries”.

China has repeatedly articulated its commitment to resolving South China Sea disputes through consultations with claimants in the region and has evaluated that these consultations on the region’s Code of Conduct have been “proceeding smoothly and effectively”, wrote Wang.