Pakistan’s forbidden romance with Bollywood

India and its neighbour have had a historically tumultuous love affair in the world of cinema, often torn asunder by real-world border tensions. A recent attack in Kashmir has their film-industry romance once again on the ropes

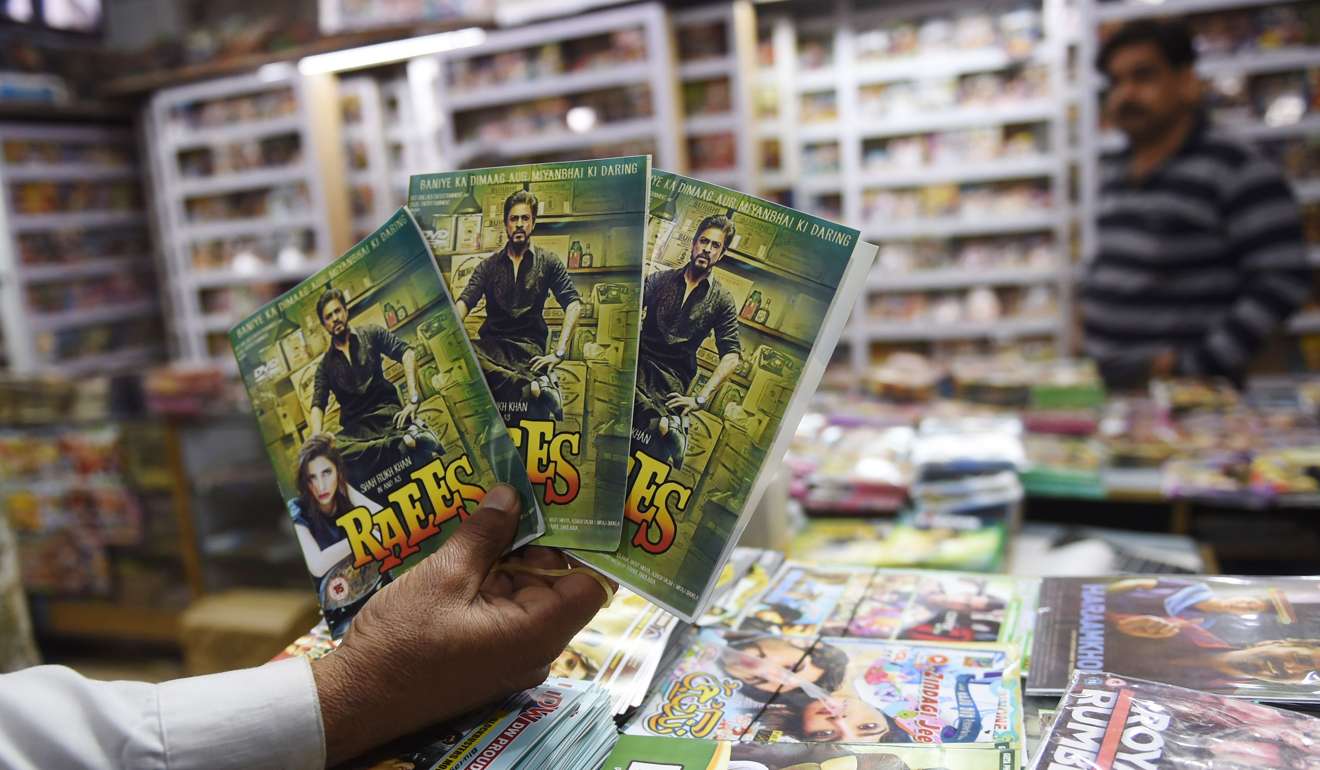

Though officially banned, the Bollywood film Raees is sure to find its fans in Pakistan one way or another, pirated for viewing on small screens if not formally approved for big ones.

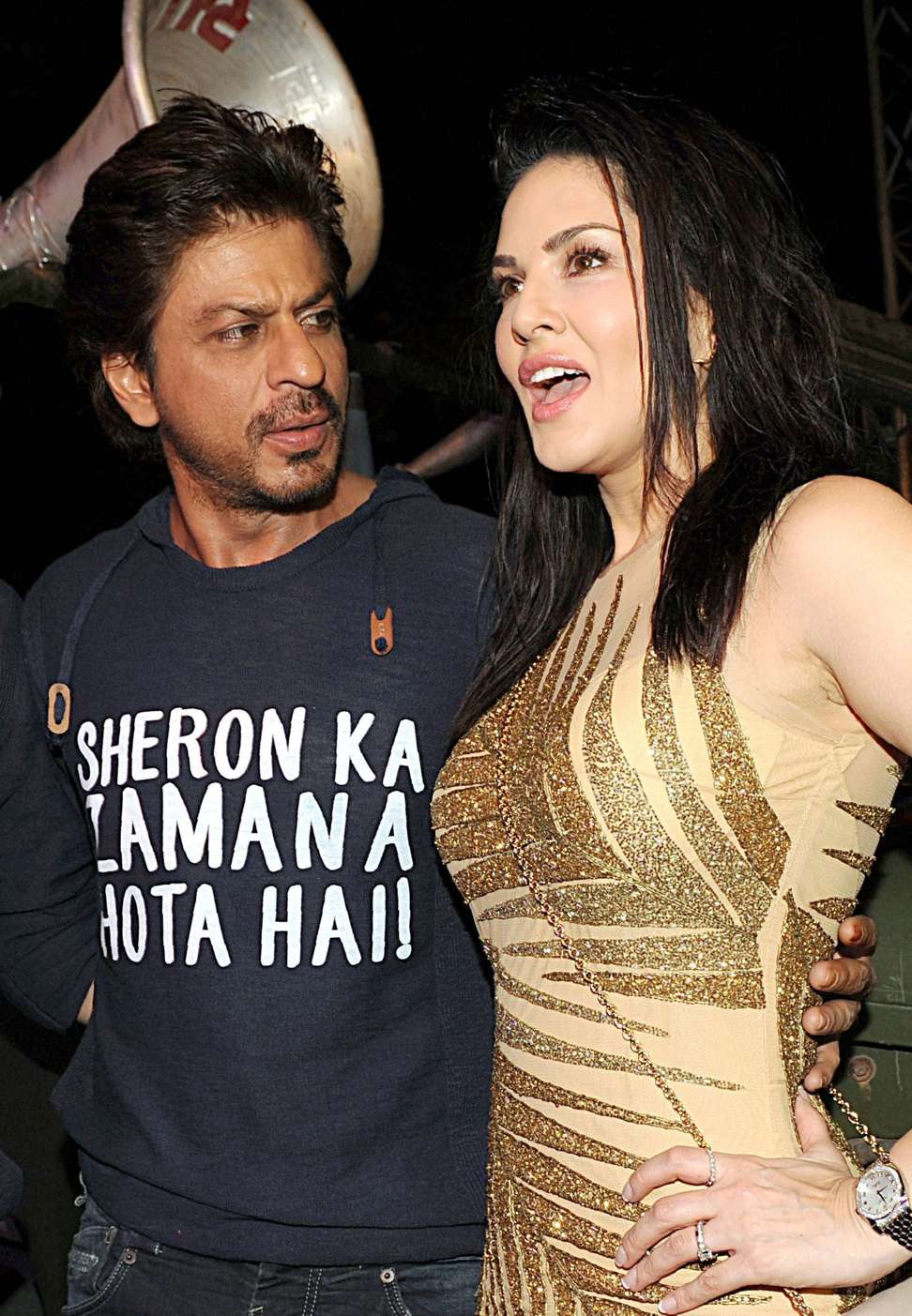

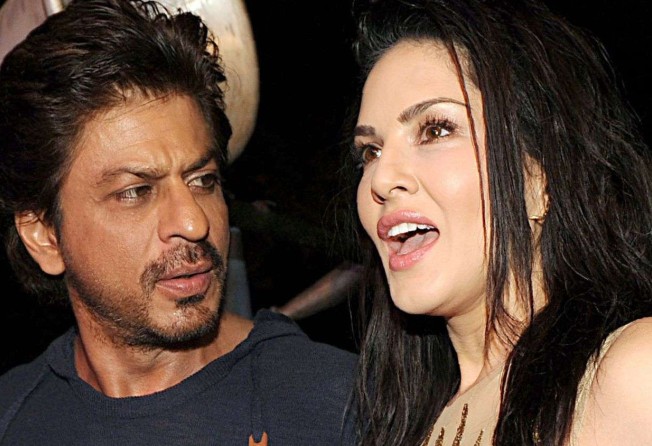

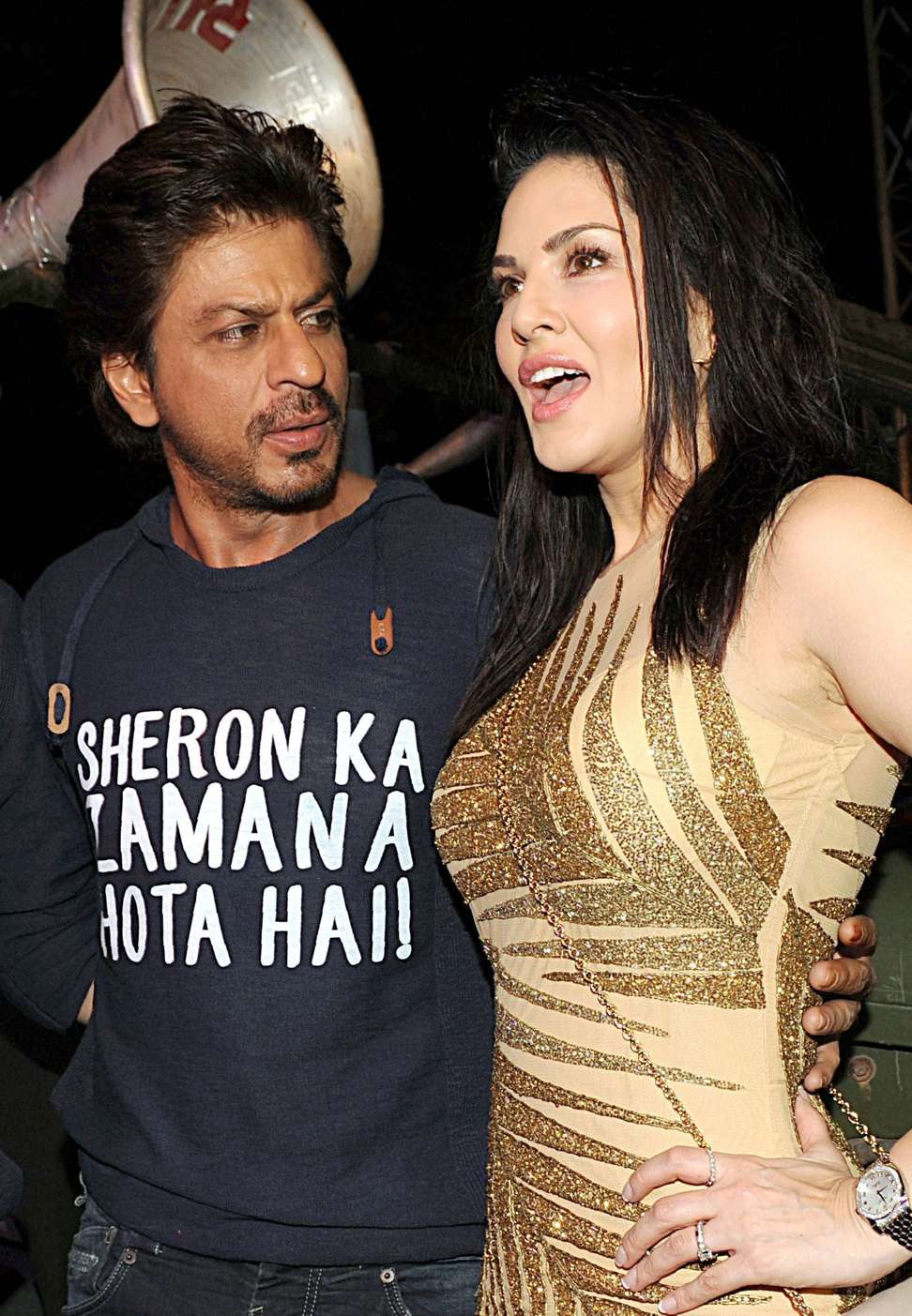

Shop owners say unauthorised “master-print quality” DVDs of the movie, starring Shah Rukh Khan and Mahira Khan, can be had for 100 rupees (HK$7.40).

Nuclear-armed and arch rivals, Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan have fought four wars but have many common cultural characteristics, including shared languages. In their spoken forms, India’s Hindi and Pakistan’s Urdu are practically identical. During a decade of detente between the two countries that lasted up to last year, Pakistani singers such as Atif Aslam and Rahat Fateh Ali Khan became favoured recording artists for Indian film producers. All Bollywood films include half a dozen or more lavishly produced musical scenes in which the leading couple lip-sync and dance to songs – often the determining factor in commercial success.

These Pakistani singers helped open doors in Bollywood for a select group of Pakistani actors. Singer Ali Zafar acted in eight Indian films between 2010 and 2016, followed by Fawad Khan’s debut in the 2014 romantic feature film Khoobsurat (Beautiful), turning the Pakistani actor into an instant heartthrob in India. Mahira was Fawad’s co-star in several popular Pakistani television dramas before she got her Bollywood break.

However, the build-up to Raees and Fawad’s second Bollywood film, Kapoor & Sons, was marred by a spike in tensions following an attack last September on an Indian military camp in the disputed Himalayan territory of Kashmir, in which four suspected Pakistani militants killed 17 Indian soldiers. The attack sparked anger in India and the worst border skirmishes since the nations agreed on a ceasefire in 2004.

Amid patriotic chest thumping by Indian right-wing political parties, Pakistan artists were expelled from Bollywood. In a tit-for-tat response, Pakistan banned the screening of Indian films in its cinemas in October. The Pakistani government lifted the ban on January 31, and Raees was lined up by distributors as the second Indian film for release in February, after being cleared by the censor boards in populous Punjab and Sindh provinces. The civilian members of the federal censorship board found nothing objectionable in Raees, but its screening was “not allowed by both the members from the [armed] forces”, a source told This Week In Asia.

In an editorial, leading English-language newspaper Dawn also blamed the Raees ban on “those shady handmaidens of censorship and state control over narrative, anti-religion and ‘anti-Pakistan’ content”. Officially, the federal board said it had banned the film for showing Muslim protagonists in a bad light. Shah Rukh Khan plays a Muslim gangster who traffics illicit liquor.

“Banning Raees because the protagonist is a Muslim, and Muslims don’t do bad things, is so simplistically ludicrous, it’s like living in la-la land,” tweeted Mehr Tarar, an author based in Lahore, the centre of the Pakistani film industry. Within the Pakistani cinema industry, there have been only a few murmurs of protest at the ban on Raees, even among social media groups. That’s because the industry has bigger fish to fry in the aftermath of the four-month ban on Bollywood films.

In a severe jolt to the movie theatre business, Pakistani cinema patrons responded to the ban by simply staying home to watch the latest Indian movies, easily available on DVD from shops or online from e-businesses with same-day home delivery services.

“Pakistani audiences love Bollywood, they identify with the actors, characters and stories. That is why they go to cinemas when Bollywood movies are screened here,” said Eman Bint Syed, the Karachi-based producer of Jalebi, a 2015 film inspired by Hollywood movies directed by Quentin Tarantino. “If you ban them, people will watch pirated DVDs. It’s unfair to punish audiences. It would be better to let the Pakistani film industry grow with Bollywood, rather than allowing the money to go to pirates.”

Screening Bollywood films in Pakistan was first banned outright after its 1965 war with India. Prior to the conflict, Indian films could be screened for a cumulative eight weeks a year. No longer having to compete with Bollywood on Pakistani screens, many producers resorted to making films that merely copied them.

“This triggered, to some extent, the downfall of the Pakistani film industry,” says Satish Anand, chairman of the Ever-ready Group, one of Pakistan’s oldest and largest film distributors and production studios. “It took the originality and independent thought out of Pakistani filmmaking.”

As a result, the Urdu film industry gradually died out by the 1980s, as middle-class families abandoned cinemas altogether to watch pirated Bollywood films at home on video cassette players, both easily rentable from retail outlets across the country.

The ban continued until 2007, when it was lifted by military dictator General Pervez Musharraf, as a result of a period of detente in relations between India and Pakistan.

“I got a call from the government, asking if I would release the Indian film Taj Mahal. President Musharraf had made a personal commitment to the producer Akbar Khan, and felt it would help to create a conducive environment for confidence-building measures with India,” said Anand.

Subsequently, his company Ever-ready was involved in the first simultaneous launch of a Bollywood film, Kohl, in India and Pakistan.

The popularity of Bollywood films among Pakistani audiences generated a wave of investment in multiplex cinemas. From none, they grew to 100 in number in 2015-16, when Pakistani cinemas screened a record high of more than 200 Indian movies. In turn, the growth of the cinema business provided impetus for the revival of Pakistan’s Urdu-language commercial cinema.

The Pakistani film industry’s comeback was heralded by the success of 2007 film Khuda Kay Liye (For God’s Sake), a low-budget feature that generated cinema receipts of more than 100 million rupees (HK$7.4 million) and turned a modest profit. By last year, Pakistani studios had produced 23 Urdu-language feature films, some of them attracting investments of up to 150 million rupees (HK$11.1 million). About a quarter of them were commercially successful, producers said. Generally, a Pakistani film has to generate three times the money invested in it to break even, because revenues are equally shared by the financiers, the production team and the distributors and cinema owners.

Producers say the single-largest facilitator of the new wave of Urdu-language feature films is the Inter Services Public Relations directorate of the Pakistani military. It provides producers with access to restricted-access locations, lends them sophisticated production equipment and selectively finances films.

The encouraging growth of Pakistan’s cinema lulled policymakers into a false sense of confidence, leading them to mistakenly conclude that locally made films could grow to fill the space occupied by Bollywood films. Instead, when Bollywood films were banned again, cinemas lost the predominant footfall of Bollywood fans, prompting cinema owners to consider selling their properties to Pakistan’s bullish real estate market – just as they had done when the Urdu-language cinema industry collapsed in the 1980s. Many private investors interested in bankrolling new films were also scared off.

“It’s a lack of understanding on part of the government and the military establishment,” said Khawar Azhar, an Islamabad-based producer and communications consultant.

“Pakistan cannot produce enough good films to fill up the local screens but at the same time we need more screens to make Pakistani films viable.

“Thus, we need more screens but we have fewer Pakistani films coming in. The only way we can keep the interest of exhibitors alive in the business is allowing Indian films.” ■■