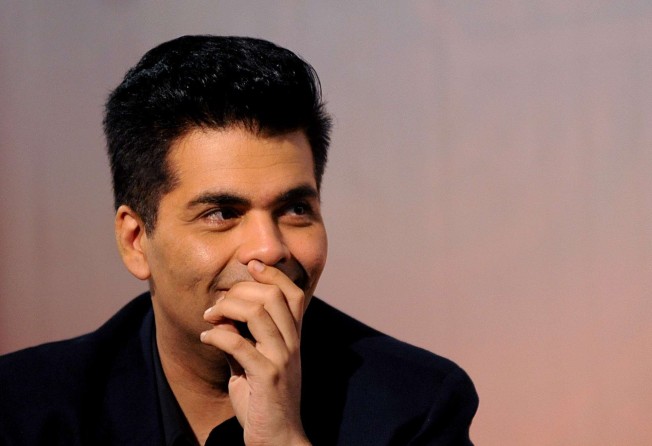

What Bollywood icon’s fatherhood says about India’s attitude to homosexuality

Karan Johar’s happy news – and his refusal to say ‘what everybody knows’ – are a reminder of the rights being denied to India’s LGBTQ community

When big-ticket Bollywood filmmaker Karan Johar announced last week that he had become a father to twins birthed through a surrogate mother, it felt like a moment he had built up to for years in both his cinematic work and his public persona.

His films have often touched on gay characters and themes, and in his public image, he has riffed on gay jokes, most often directed at himself.

Now, with the birth of Yash and Roohi, a boy and a girl, Johar is thought to be the first gay, single man in India to have become a father through surrogacy (and only the second single man; the first was Bollywood actor Tusshar Kapoor).

Yet any hopes that Johar’s fatherhood may open up possibilities for the gay community must be tempered; not only does gay sex remain a criminal offence in India, plans are afoot to ban gay men from following Johar’s path to fatherhood.

“Everybody knows what my sexual orientation is,” Johar writes in his autobiography An Unsuitable Boy. “I don’t need to scream it out. If I need to spell it out, I won’t only because I live in a country where I could possibly be jailed for saying this. Which is why I, Karan Johar, will not say the three words that possibly everybody knows about me.”

Under the Indian Penal Code inherited from the British colonial administration, Section 377, titled Unnatural Offences, holds that, “Whoever voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal, shall be punished with imprisonment for life, or… for a term which may extend to ten years, and shall also be liable to [a] fine.” The principal targets of this law are gay men, but it also criminalises heterosexual acts like oral and anal sex.

Section 377 is a vicious homophobic legacy that binds some former colonies of the British empire, yet not its original framers. While the law remains in use in Pakistan, Bangladesh, India, Malaysia and Singapore, the British have moved on with their views – Britain’s 1967 Sexual Offences Act decriminalised consensual sex in private between men above 21.

In India, Section 377 has shaped a public culture that shames and mocks gay men, even seeks to cure them, forcing them into secrecy and denial. Treatments for homosexuality in India include proposed government-run centres for curing homosexuality, electric shock and hormone therapy and “corrective rape” by parents.

Several months before Johar’s news, in November 2016, the right-wing BJP government tabled the Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill, 2016, in the Lok Sabha (lower house of parliament). The bill seeks to establish strict regulations for surrogacy in India, a country which has in recent years become popular for its rent-a-womb possibilities.

There is good reason for strict monitoring of the lucrative surrogacy industry that has sprung up: as such, the bill bans commercial surrogacy. It also bans foreigners from seeking surrogate mothers in India, and even Indians who already have a child from doing so. But the bill goes further: it also bans gay couples, unmarried couples and single individuals from becoming surrogate parents. In so doing, the government seized the opportunity to spell out its idea of what constitutes a family. “We do not recognise live-in relationships and homosexuality,” external affairs minister Sushma Swaraj said. “We don’t give them this entitlement.”

The right to have a family is enshrined in Article 16 of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights and other international rights documents. The Indian government is thus seeking to deny certain citizens a fundamental human right.

The bill is likely to be passed in a matter of months – it had already secured approval from the cabinet of ministers before it was introduced in parliament.

Johar’s news, if anything, is a reminder to the gay community of what they cannot have. “I do hope to have children myself,” said Parmesh Shahani, head of the Godrej India Culture Lab, and author of the non-fiction book, Gay Bombay: Globalisation, Love and (Be)Longing in Contemporary India, said.

“There have been studies on parenting done globally for many years now. Nowhere do the results of these indicate that heterosexual couples are better at parenting than others. I hope [the government] will rethink this after careful consideration.”

“It is unfair,” said Jay Panda, an MP who moved a private member’s bill on transgender rights in the Lok Sabha (Lower House) of parliament in 2014 after it was passed by the Rajya Sabha (Upper House). “I expect there will be opposition to these clauses. If not, I am prepared to move amendments myself.”

A Different Note

The mainstream English-language media has welcomed Johar’s news. “Its Yash and Roohi, says dad,” read the headline in The Telegraph. “Father Karan Johar introduces twins Roohi and Yash to the world,” said NDTV. “Karan Johar becomes father to twins, names them Yash and Roohi,” said HuffingtonPost India.

The English-language media in India had played a role in changing the tone of the public conversation regarding gay people, said Sandip Roy, journalist and author of the novel Don’t Let Him Know, and a LGBTQ rights advocate. “There was a whole class of activists who worked very hard especially with English language media in changing perceptions,” said Roy.

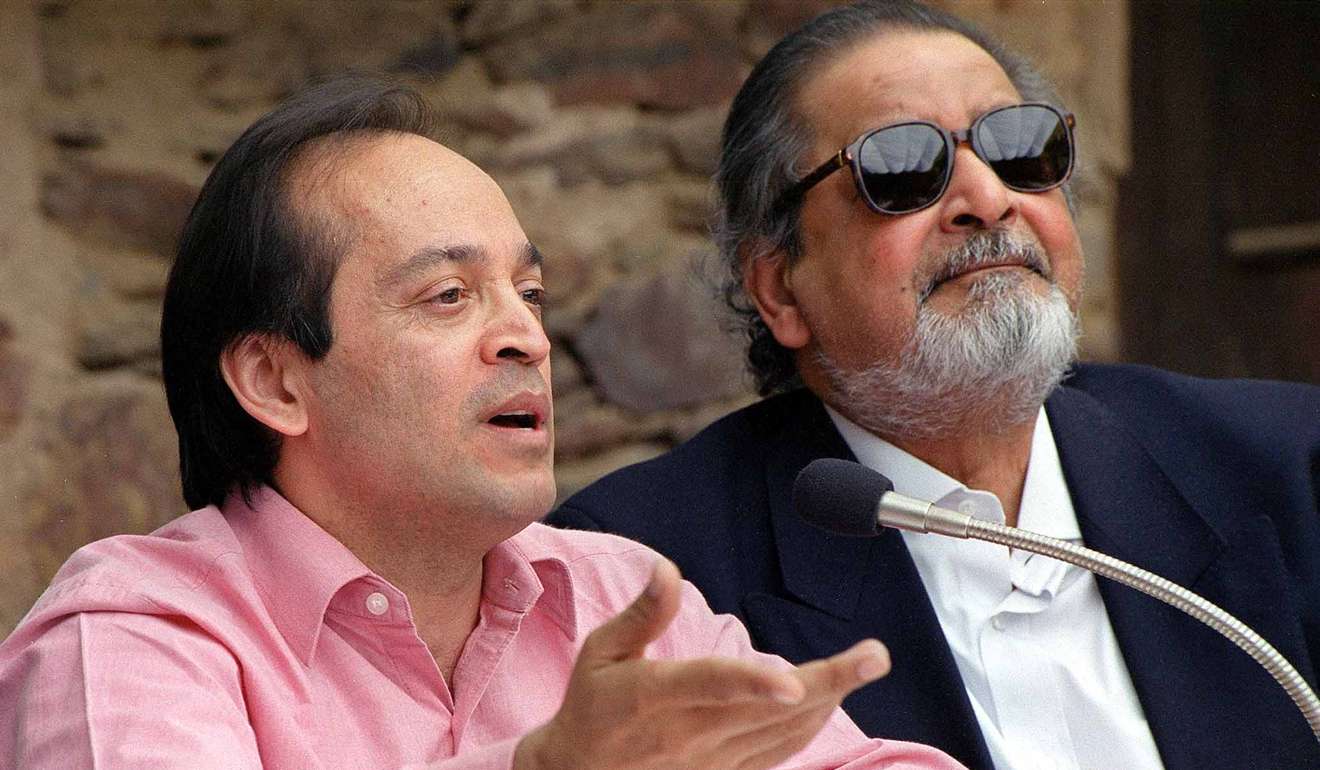

“These included the novelist and poet Vikram Seth and Nobel prize-winning economist Amartya Sen who wrote an open letter to India Today, with Seth appearing on the cover, after a Supreme Court ruling that backed the Section 377 ban.

“I think the measure of that was how many newspaper editorials lambasted the [reinstating of the ban]. I can’t think of a single English-language editorial that supported it,” Roy said.

In 2009, the Delhi High Court had struck down Section 377, saying it went against the fundamental right to equality, and the rights to personal liberty and freedom of expression guaranteed in the Constitution. But in 2013, the Supreme Court brought it back.

A record of the court proceedings, maintained by the Alternative Law Forum, offers an astonishing account of the judges’ (lack of) understanding of the gay community in India.

Among other things, the judges asked questions such as “do you know any person who is gay”, and “what is a bisexual?”

Lawyer Anand Grover, who represented the battle against Section 377 in the Supreme Court said the Surrogacy Bill was “homophobic, discriminatory and wholly unconstitutional” and a “blatant violation of an individual’s fundamental rights”.

There has, nevertheless, been a marked increase in the visibility of the gay, indeed LGBTQ rights conversation in the years since 2009. There are now gay pride events in several cities, queer film festivals and movies with gay characters even as the government and courts clutch to Section 377.

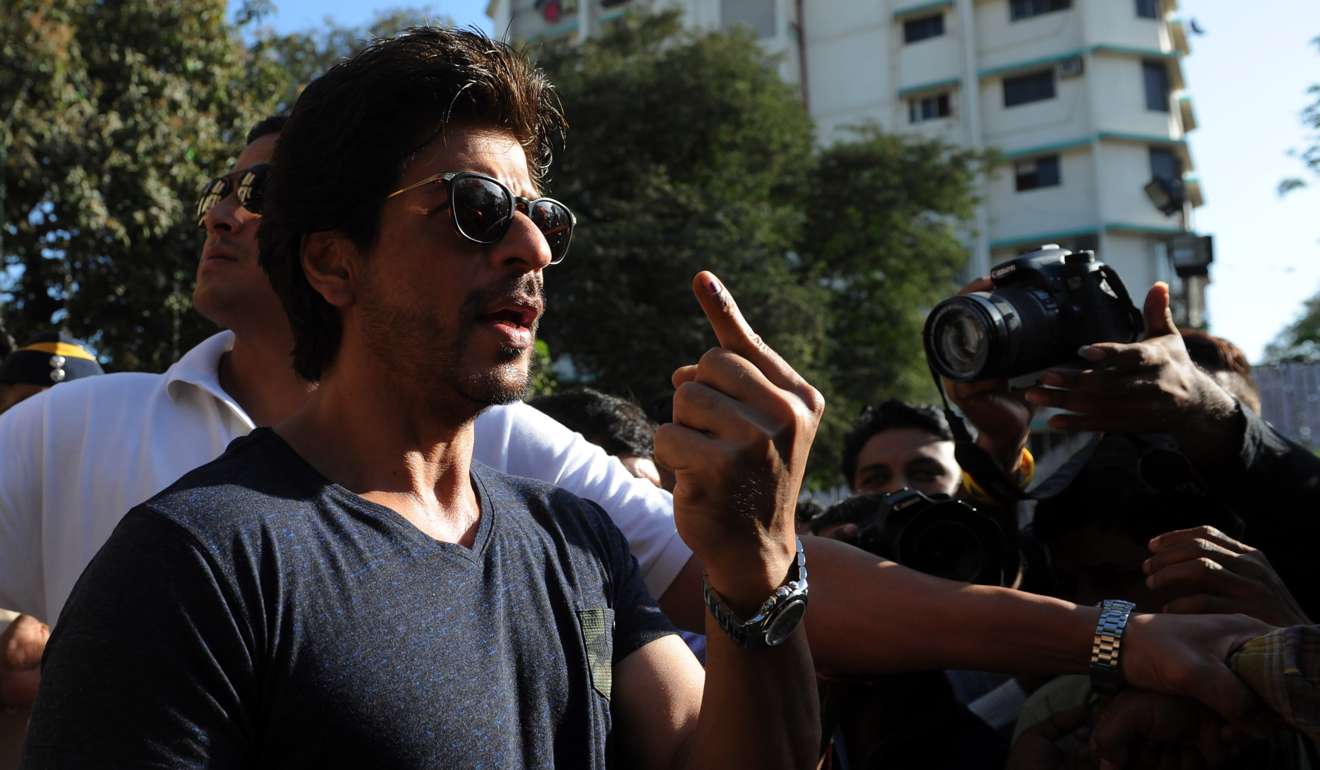

Johar has shown no inclination to be an activist but some would grant that Johar, too, has contributed to this change – moving from awkward gay jokes to somewhat nuanced depictions of gay characters in his films. In a 2002 blockbuster called Kal Ho Naa Ho that he wrote and produced, there was a running gag featuring Bollywood stars Shah Rukh Khan and Saif Ali Khan that involved a maid being shocked at what she mistook to be gay intimacy.

In 2008, Johar produced Dostana, where the two male leads, played by John Abraham and Abhishek Bachchan, pretended to be gay.

Once again, the film skirted around the topic and received poor reviews from many critics for being humbug and playing to all the gay stereotypes, yet the film ends on a curious note: the two leading men kiss on a dare but seem to be pleasantly surprised by the experience. In 2012, Johar wrote, directed and produced Student of the Year, where one of the important (though not central) characters, played by the star Rishi Kapoor, turns out to be gay and regrets having lived in denial.

The next year, in 2013, he directed a segment of an ensemble film called Bombay Talkies, where an out-of-the-closet homosexual makes an advance on a closeted man and brings a stilted marriage to a point of reckoning. The film earned him rich applause. In 2016, Johar produced Kapoor & Sons, a critical and commercial success, in which one of the leads was a gay man free of the usual stereotypes.

In his public persona, Johar has, for years, played along to risqué jokes regarding his “effeminate” manner and rumoured affair with Shah Rukh Khan. In 2015, on the live comedy show AIB Roast, he joked about being the “bottom” in a gay relationship. This year, he published his memoir, in which he effectively comes out – without saying “the three words”.

By the standards of Indian public life, where there are few gay celebrities, Johar is unusual. There are others who have produced films and art on gay themes, many of them more acclaimed than Johar. The late Bengali filmmaker, Rituparno Ghosh, stands out in particular – like Johar, he tackled homosexuality in his films and his Bengali talk show. But unlike Johar, who wants to be liked, Ghosh forced his audience to accept that he was different with his very public shift towards a feminine appearance in the last couple of years of his life.

Many in the LGBTQ community are disappointed that Johar refuses to say those three words. “There is also concern that while doing so, he is perhaps spreading misinformation,” said Shahani. “The law as it stands in India, does not criminalise being gay, it criminalises same-sex acts, but Johar seems to be afraid that just acknowledging one’s sexuality is an offence, which it is very clearly not. Since he is such a prominent public figure, who reaches millions through his films and TV shows, this hesitance on his part is a source of great disappointment to many in the LGBTQ community.”

In a sense, Johar’s reluctance is not unlike the Indian state’s attitude towards homosexuality: confusion, perhaps an edge of panic. Indians now engage with gay characters in mainstream cinema, they have conversations on homosexuality on prime-time news television, they may not have come to acceptance yet but there is certainly acknowledgement of homosexuality. In response, the Indian state has chosen to leap several steps back – drafting a surrogacy law that discriminates against the homosexual community, and spelling out what it defines as a family.

Johar’s fatherhood then is an ambiguous moment – a happy moment for the man, but a reminder for the homosexual community of the distance between acceptance and denial. ■