The truth-vigilantes fighting India’s fake news

It’s ‘our way of helping society’, say two men in Bangalore whose mission is to bust false messages circulating on WhatsApp

Seeing Shammas Oliyath work at 10pm, as he does almost every night, one is reminded of Arnold Schwarzenegger in The Terminator. Except Oliyath has a calm personality, a benign smile and works on a computer.

He is targeting a barrage of forwarded messages on WhatsApp, trying to separate the true ones from the fake. And it is not child’s play.

Oliyath, along with his business partner Balkrishna Birla, founded check4spam.com in 2015. Their main task is to bust fake messages floating around on WhatsApp.

Why? “That is our way of helping society,” says Birla. Both have day jobs in large software companies in India’s tech capital of Bangalore. Their avocation is undertaken in the dead of night after a gruelling day of work and after household chores are done.

Their choice of medium is not incidental. WhatsApp has more than 1.2 billion users globally, and more than 200 million are in India. And users continue to grow along with the number of mobile internet users in the country, now estimated at more than 346 million.

Unlike Facebook or Twitter, WhatsApp doesn’t require users to set up an account – only a smartphone is required. And, most importantly, WhatsApp messages are not public. They are, at most, limited to a group of people. This personal touch makes it a more impenetrable echo chamber, as there is often no one to counter argue – no one to point to an alternate source of news.

This, the pair believes, is what makes forwarded WhatsApp messages potentially more effective for those who wish to disseminate fake news.

This is how Check4Spam works: A WhatsApp user sends a message to check. The message reaches Oliyath and he gets cracking on it late at night. He gets about 150 such requests every day. He says some of them take a long time to verify as he has to do extensive searches online.

In one example in early January, a forwarded message linked to a story titled “Dawood’s assets worth 15,000 crore seized in UAE”. It was curious that news about Dawood Ibrahim, India’s “most wanted man” broke out merely weeks before the UAE’s Crown Prince was to be the special guest at India’s Republic Day parade held on January 26. Soon, many mainstream media outlets in India picked it up and published it.

Upon investigation, Check4Spam determined that the source, OutlookIndia, referred to Financial Express, which referred to ABP News, which referred to Zee News, which referred to itself, which Check4Spam could not find anywhere.

Subsequently, the UAE’s Ambassador in India dismissed the reports. He emphasised that he did not know of any such assets seized. But reputable newspapers, magazines and news websites had already reported it.

When such strong rumours do the rounds, Check4Spam can draw more than 1,000 users to its site.

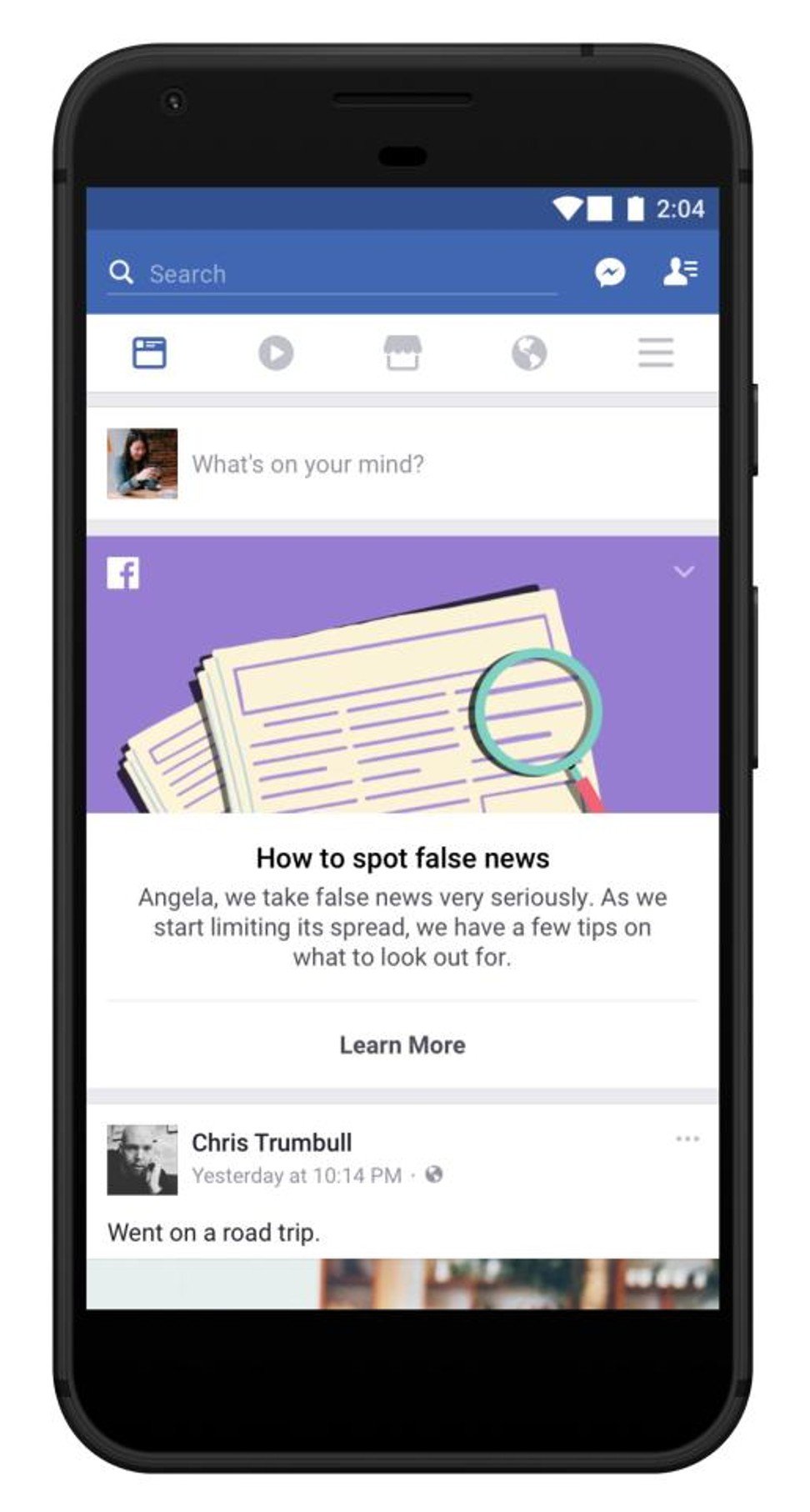

So-called “fake news” is a global problem, and media institutions and governments are treating it as a public threat. Google and Facebook are also trying to weed out websites that carry fake news. Unlike in Malaysia and Singapore, where the government takes an active role debunking fake news, in India efforts to curb misinformation are being carried out in small pockets, usually by not more than a few dozen people.

FactChecker.in and hoaxorfact.com are two other fake-news-fighting web services in India, however they are not limited to WhatsApp forwards. FactChecker verifies “claims/statements made by public figures or government reports and checks for veracity and context”. HoaxorFact checks “all kinds of scams, viruses, deceptions, misconceptions, misbeliefs, and unfair hoaxes and rumours”.

Reporterslab.org has an online list of similar fact-checking websites across Asia.

In March during a seminar hosted by media-tech website MediaNama and the newspaper Mint, many opinion makers at the intersection of journalism and technology debated the phenomenon of fake news.

WATCH: Matt Damon on fake news

Lawyer Apar Gupta pointed out that the UN special report defines fake news as that which “overwhelms the democratic process, prevents people from taking political decisions”. But Rohan Venkat, news editor for Scroll.in, disagreed. He said such messages need not be political. As an example, a WhatsApp message that predicted a sharp rise in the price of salt made people buy and hoard salt, he said.

Birla of Check4Spam believes there are three kinds of fake news: ideological, financial (fake promotions) and mere nuisance messages.

Ideological messages are political or religious in nature. As an example, Oliyath pulled out his phone and showed a video of two Sudanese being beaten up in South Sudan, but the video is captioned “Hindus tortured by Muslims in Uttar Pradesh”.

In 2013, religious riots that killed 62 people in Uttar Pradesh were triggered by a fake WhatsApp video that went viral.

What Birla calls “financial or promotional messages” come from companies that lure people with their fake products or promises, often in an attempt to install viruses on their phones that tap into their personal data.

And attention-seeking messages “help no one”, said Birla. For instance, there was an image that went viral of a woman having birthed 11 children at the same time. Oliyath discovered through a simple reverse image search on Google that it was a woman who had a tumour in her stomach and the babies were from a completely different image.

“The most dangerous is the first category,” Birla said. And Oliyath agrees that their numbers are growing.

“There are fake news factories, and there are people making WhatsApp forwards daily, and they do a trial-and-error thing to see which is spreading,” said Meghnad Sahasrabhojanee, a Delhi-based political analyst at the MediaNama seminar.

As of now, a mammoth battle is being fought by a tiny army of motivated people. Oliyath says he will continue to sit down in front of his computer, labouring into the night.