America has come to terms with Indonesia’s past. Why can’t Indonesians?

The US has declassified documents regarding the 1965 coup that led to 500,000 deaths and the fall of Sukarno. They make for chilling reading

Bedjo Untung holds a list of 122 place names around the island of Java that runs eight pages long. They include names of small out-of-the-way places like Hutan Barisan and Bukit Wonosegoro. They sound unremarkable except that they are the home to mass graves.

This week that list grew longer. Untung, who heads the country’s largest survivors group of the purge of suspected communists in 1965, says he presented 10 more place names to Indonesia’s semi -governmental National Commission of Human Rights, bringing to 14,500 the number of bodies his organisation, YPKP 1965, believes are strewn throughout the country as a result of one of the worst atrocities of the late 20th century, a period that claimed an estimated 500,000 lives. “That’s just on Java. There will be more [graves],” he said. “Victims are scattered all over. It’s only a matter of time.”

Last week Bedjo’s search received a boost when the US government declassified some 30,000 pages of documents originating from its Jakarta embassy spanning the period of the worst of the bloodshed. For many the avalanche of paper represents a chance to push a recalcitrant government toward confronting the country’s bloody modern history.

“If America is willing to see the truth, maybe Indonesia will follow,” he says.

That will be tricky. Communists are something of a bogeyman here. They are blamed for attempting the 1965 coup, which led to the fall of Sukarno and the installation of Suharto soon after.

The declassified documents come at a time when Indonesia is seeing a resurgence of some of the sectarian and authoritarian undercurrents that were responsible for the killings, rapes, forced labour and detentions of the 1960s and 1970s.

In September, Islamic vigilantes surrounded and threatened to storm the headquarters of a human rights NGO in Jakarta on suspicion that it was harbouring communists. It was not.

The group, Lembaga Bantuan Hukum, which offers free legal aid to victims of human rights abuses, was holding an event featuring survivors of the mass killing.

“Indonesia needs to be able to have a dialogue about this,” says Galuh Wandita, author and director of Jakarta based NGO Asia Justice and Rights. “If you even talk about it [the purges] you are branded a communist.”

The latest surge of anti-communist hysteria comes despite, or perhaps because of, foreign and domestic pressure aimed at nudging Jakarta towards officially investigating the atrocities, including the mass graves that extend from Sumatra to Java, Bali, and Sulawesi.

In 2012 the Human Rights Commission wrapped up a four-year investigation into the purges. It’s final report was blunt, concluding the state explicitly sought to “exterminate” members of the Communist Party, known as PKI.

Neither the release of Joshua Oppenheimer’s documentary The Act of Killing, nor President Joko Widodo’s symposium last year, which focused on the purges, have resulted in much.

Those who may have something to lose from an official investigation are in a position to squelch it. Three Suharto era generals serve in Widodo’s cabinet, and his minister overseeing security, Wiranto, is wanted by the United Nations for war crimes.

“There is no political will to investigate,” says Reza Muharam of activist group IPT 1965. “It’s one step forward, two steps back.”

In 1965, Indonesia had the world’s third-largest communist party after China and the Soviet Union. The president of the time, Sukarno, was staunchly socialist and anti-America. The violence began after the communists were accused of killing six top generals in an attempted coup.

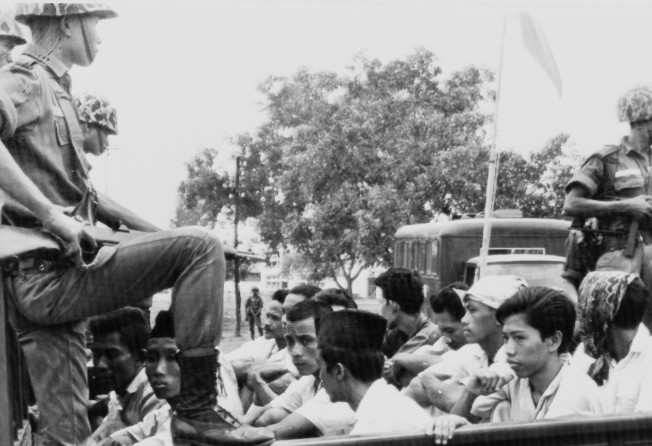

The newly released documents add to mounting evidence that the military was behind a systematic purge of suspected communists and had help from religious groups. Declassified on October 17, and comprising reports and diplomatic cables to and from the embassy, they show US officials were pleased when Indonesia’s military installed martial law.

The cables also went some way to underscore why, 50 years later, Indonesia’s elites may be loathe to allow details of the systematic killings to come to light. One cable, titled “PKI Hunt in Central Java”, details how commandos sought help from local religious groups including Catholics and members of the Nahdlatul Ulama, the country’s biggest Muslim organisation, to “root out PKI elements” in the Central Java regency called Kudus. The commanding general of the country’s commandos at the time, Sarwo Edhie Wibowo, was the father in law of the previous president, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono.

Activists warn that the atrocities extend beyond the grave. Millions of family members were thrown out of schools, government jobs or shunned by neighbours. Many more like Untung, now 70, were jailed for years simply for being members of a union. Untung was jailed for much of his 20s in Jakarta and was regularly tortured during the first year.

“It is my special duty to seek compensation for property that has been confiscated by the government and for our lost livelihoods,” Untung says.

Others, like Aris Irianto, were not jailed but are nevertheless haunted. A slight looking 63-year-old man who fidgets with his pipe more often that he smokes it, Irianto recalls as a boy bringing food twice a week to his father. “My mother and I would go visit him at the camp but I would turn and clutch her when I heard the guards beat some of the men,” he says.

“I never saw them. I just heard it. They did this to scare the families. I’ll never forget it to this day.”

Activists are split on whether there is cause for hope. Some say young people nowadays have fewer hang ups about the purges and less appetite for propaganda of the era. Untung is not so sure; he says it will take pressure from the US and other countries to encourage Indonesia to face its past.

On a recent Thursday, he was preparing to join about 40 other members of his victim’s group for a small, peaceful protest outside the Presidential Palace in Central Jakarta. They have been doing this for 550 weeks already.

“Today is the 551st week,” Untung says. “The road to reconciliation is still long and difficult.” ■