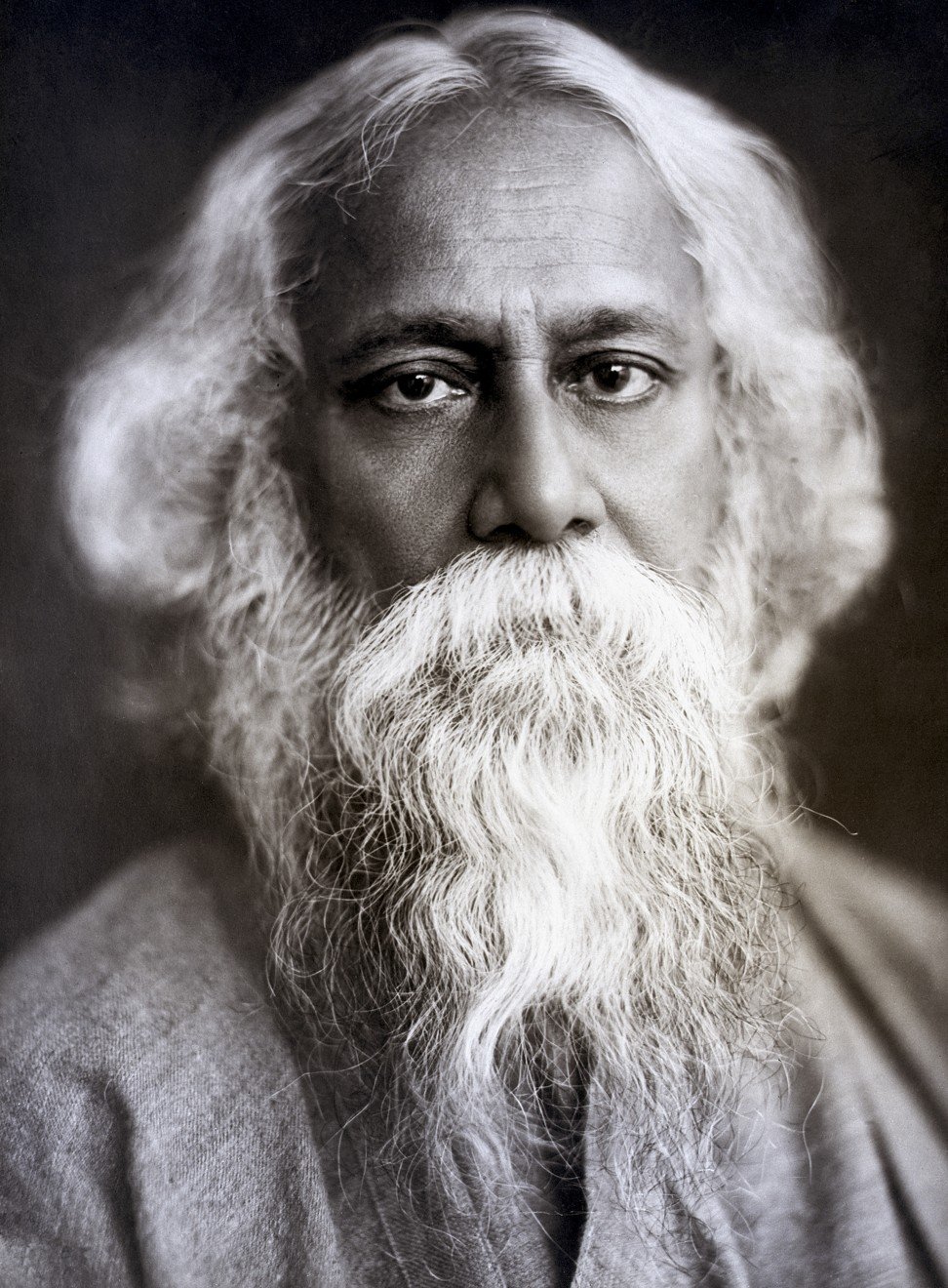

Is China’s secret superstar Aamir Khan the second coming of India’s Tagore?

The Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore’s enchanting stories prompted a watershed moment in Sino-Indian ties. Almost a century later, a Bollywood superstar is on the cusp of doing the same

From the Buddha to Tagore to Aamir Khan, the Chinese have always been captivated by India’s cultural icons.

While the Buddha has long had a deep impact across the Himalayas, Rabindranath Tagore’s stories have enthralled Chinese readers since the early 20th century, and then Bollywood stars Raj Kapoor and Nargis got them humming Indian film songs in the 1950s. Most recently, however, Aamir Khan has drawn a new generation of Chinese fans to the power of Indian storytelling.

Secret Superstar is the latest Aamir Khan vehicle to charm Chinese audiences, collecting more than US$30 million in the first four days of its release – double what his previous, and extremely well-received, film Dangal (Wrestling) grossed in China during the same period.

With this success, Khan has joined the ranks of Raj Kapoor and Nargis, whose film Awara (The Vagabond) has become ingrained in the memories of Chinese since the mid-20th century.

Like the song Awara hooh (I am a vagabond) – from the 1950s film – which resonates with older generations who grew up watching Russian and Indian movies, young Chinese people today are flocking to theatres to watch Aamir Khan films because they relate to the storylines.

Be it the college life portrayed in 3 Idiots, the stringent expectations of a “tiger dad” in Dangal, or the familial struggles of an aspiring singer in Secret Superstar, the plots are realistic, entertaining and moving. Even Khan’s sci-fi PK did extremely well in China, largely thanks to his acting and storytelling.

Such success places Khan on the cusp of overshadowing Tagore’s cultural impact on China. The first Asian to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913, Tagore was an instant celebrity in China, with Chen Duxiu – a future founder of the Chinese Communist Party – as one of the first translators of the Indian poet’s works.

However, when Tagore arrived in China on his first visit in 1924, opinions about the Nobel laureate were mixed.

The May Fourth Movement of 1919, which sparked anti-colonial protests, had given rise to Chinese patriotism, which did not gel with Tagore’s criticisms of the dangers of nationalism and nation-states. But even though several prominent Chinese intellectuals expressed strong opposition to his political stance, Tagore’s visit accelerated the translation of his literary works and inaugurated the so-called Tagorean phase of India-China relations, which saw the two countries frequently exchange artists, intellectuals and students.

Then, the “Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai” (Indians and Chinese are brothers) phase in the 1950s saw the exchanges of several goodwill missions organised by the Indian and Chinese governments, promoting mutual awareness and understanding.

The film Awara – in which the protagonist, the son of a judge, turns to crime – played a big part in these exchanges, screening in 20 Chinese cities as part of Indian Film Week in 1955.

Watch: Awara Hoon song from 1951 film Awara

The film appealed to Chinese youth not only because it reflected some of the socialist values they were imbued with in Maoist China, but also because the singing, dancing, and comedic performances provided a momentary release from their strenuous lives. Awara remained popular through to the late 1970s with younger generations who emerged from the decade-long torment of the Cultural Revolution and were unaware of the war between India and China in 1962.

Like the tales of the Buddha’s previous births that first enchanted the Chinese, Tagore’s mesmerising short stories – with their tussles between modernity and tradition, the national and the global – or the account of a vagabond in Awara, Khan’s films could again captivate generations of Chinese film-goers.

Each stage of this storytelling led to a watershed moment in the relationship between India and China. At this current state of volatility in the India-China relationship, will Khan’s stories also result in the creation of a new watershed moment? If that does happen, Khan will have to be acknowledged as the second coming of Rabindranath Tagore. Then historians in the future, looking back at this moment, might even feel tempted to call this the “Khan phase” of India-China relations. ■

Tansen Sen is the director of the Centre for Global Asia at NYU Shanghai and the author of India, China and the World: A Connected History