‘Say hello to my little friend’: is there a Hollywood ending to Duterte’s drug war?

The bloody national campaign may be popular with the public, but there are some people getting addicts off the streets without firing a shot

If American director Brian De Palma’s Scarface taught viewers anything more than a few great lines of dialogue to spice up pub chatter, it was that the illegal drugs business is a violent one and even successful careers can unexpectedly end in gruesome death – often carried out by colleagues.

If much of the world’s media is to be believed, there’s a modern version of the flawed masterpiece being played out right now in the Philippines that rivals the excessive violence of the 1983 film. But as with many reboots, the roles have been flipped.

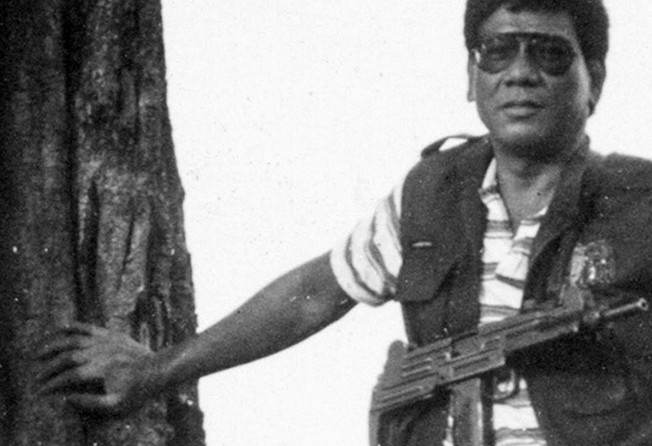

Al Pacino’s ferocious anti-hero Tony Montana, who stops at nothing to rise from Cuban immigrant to powerful drug lord, is now foul-mouthed Rodrigo Duterte, a president seemingly stopping at nothing – mowing down human-rights charters and racking up a body count in the thousands – to free his country from the scourge of “shabu”, the popular name for methamphetamine.

At the advice of Filipino politicians, the International Criminal Court (ICC) has begun investigating whether Duterte’s crackdown involves crimes against humanity. A common complaint about The Hague is why it seems to focus on leaders who have fallen foul of the West and not the likes of former US president George W Bush and ex-British prime minister Tony Blair, whose invasion of Iraq based on spurious information led to the deaths of about a million people. Duterte agrees and has told the ICC the Philippines is leaving.

The flaw in the sensational drug war coverage is that rarely is it suggested that the gangs might be doing some of the killing.

“You cannot attribute all the killings to the police – it’s very infantile. Drug syndicates everywhere operate in a violent way,” said Luciano Felloni, a priest in Metro Manila. “You were given a kilo of shabu and then you did not remit that money and so the syndicates will kill you … that makes perfect sense.”

Felloni, from Argentina, trained at a seminary in Buenos Aires where Pope Francis taught – he even confessed to him several times. He has been in the Philippines more than 20 years and works in Caloocan city’s Barangay 174, which has seen dozens of drug-related deaths since Duterte’s crackdown began, some at the hands of police.

The son of Rolando dela Cruz was killed by unidentified gunmen. Rolando earned money from an illegal “video karera” horse racing machine and spent the profits on drugs. One night in April 2017, masked men burst into his home and shot his son in the head, killing him on the spot. If Rolando hadn’t nipped out for five minutes to get change for the machine, he might also be dead.

After two months, they created the Community Assisted Rehabilitation and Recovery of Outpatient Training System (Carrots), a programme that mixes psychology, counselling and spiritual guidance to get people off drugs, give them skills, keep them mentally and physically fit and put them back in the community without a shot being fired or anyone going to jail.

“At the beginning we had a lot of threats,” Felloni recalls. “A lookout car was like for two months always there [on the street outside]. Then people with masks would come asking for me. It’s a good thing many times I was out. I think … the police were suspicious of us, the government was suspicious, the syndicates … I don’t think they would be very happy about us.”

The drug syndicates may be more careful due to the crackdown but they haven’t stopped operating and shabu is still widely available, just more expensive.

“We are under budget, we are undermanned, we are under-equipped,” complained Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) Director General Aaron Aquino.

“We just have about 1,251 agents distributed nationwide and it’s quite difficult to address the problem. In Nueva Ecija alone, for example, with about 32 municipalities and cities, we have only three personnel assigned there to address the problem of illegal drugs with about 2 million people. So, it’s actually next to impossible.”

Aquino said PDEA has a “private eye” programme with a budget of 5 million pesos (HK$750,000) per quarter to reward informants whose tips lead to “successful operations”. “For example, there are clandestine drug laboratories that were dismantled and these were brought about by the information given to us by these action agents. They are cooking drugs here.”

One of the labs was in Cauayan, Isabela province, in the far north of the country. PDEA agents picked me up from the airport in a rickety estate car with a broken driver’s seat and faulty knobs to wind down the windows – a vehicle that could definitely benefit from a little bit of “reward money”.

Like Nueva Ecija, there are only a handful of agents in the province, but they make do with what they have to get their jobs done.

The meth lab I was taken to was set up by Chinese operators and capable of making more than a tonne of raw shabu every month. They rented the warehouse from a local official and pretended to run a business selling appliances and plastic products. No arrests have been made in connection with the bust. The two Chinese men in the warehouse were killed trying to defend the place with machine guns. “Some of the drug dealers that manufacture in other countries came here to the Philippines to manufacture because here there is no death penalty,” PDEA agent Gaudia said.

Duterte’s proposal to bring back the death penalty for drug crimes has given his critics more ammunition for their assertion that he is a bloodthirsty dictator. But the move would only put the Philippines in line with much of Asia. “More drugs are being brought to the Philippines [than made here] … either through airports or seaports,” Aquino said. “Others are bringing drugs … they call it shipside smuggling, where the drugs are being thrown on high seas and then a couple of small ships get the drugs, bring them to the shore, and bury it there. After a few days, they get the drugs and put it in a warehouse.”

The Philippine Coast Guard is cooperating with its counterpart from China – where most of the drugs come from – to intercept smugglers and pirates.

It’s thought that mainland Chinese and Filipino fishing boats get the drugs to shore in northern provinces, like Isabela and Pangasinan. From there, syndicates redistribute the shabu until it ends up in the hands of people like Jay Bilos in Barangay 174.

He twitches and fidgets constantly as he recalls his rise from being a poor tricycle driver to a successful shabu dealer, feared in the neighbourhood.

Fed up with driving people around all day for a few hundred pesos, Jay began selling drugs. He was paying 200 pesos (HK$30) for 300 pesos worth of meth. His friends would buy it and even share it with him.

Jay was living it up, he thought at the time, earning around 1,500 pesos a night – more than he could earn battling traffic and breathing toxic fumes all day on his motorbike. He became known in the barangay as the guy you could score from. But his decadent new lifestyle didn’t last.

He was constantly high and gambled away everything he earned, leaving nothing for his family.

Neighbours still joked with him, but there was fear behind their smiles. They would even move their slippers indoors in case he stole them.

His wife left him and within the space of a year or so his mother, father and grandmother all died, leaving him alone to look after his two-year-old son. In desperation, he turned to the church for help. “I cannot live like this forever. I’m already old. Do I have to be this way?” he remembers asking Father Felloni.

Just last year, Jay says, he would have “run like a rat” when he saw a policeman. Now he’s joined Carrots and, along with Rolando dela Cruz, is no longer worried about getting caught or shot because he knows he’s doing the right thing. He’s been ostracised by his former drug-user friends, but that won’t stop him from trying to convince them to go straight because he believes “change is in their hearts”.

“The thing that I can do to continue the changes in my life … is to also be the one to help,” said Jay. “We will also do the same thing.”

While law enforcers may be struggling to get a grip on the national drug problem, Bunag and Felloni’s home-grown solution to clean up their neighbourhood has been a success. So much so that the programme has spread to more than 35 barangays without any help from the government, which has taken notice, as it puts more of an emphasis on localised anti-drug programmes.

The pair met officials in Malacanang Palace to discuss Carrots and where it’s going. There was a lot of hope before the meeting that the government might adopt the programme, making it policy and sharing the burden.

“We have a good partnership with the barangay, a good partnership with the city of Caloocan, but almost nothing with the national government,” Felloni said after the meeting.

“We believe it will be better for the whole community if we work with as many people as we can together.”

“This was the first time I heard from Malacanang a holistic approach … [They had] a beautiful whiteboard full of charts and projects and areas. I asked, are you piloting any of this? ‘Not yet’ [they said].”

In a few months, Duterte’s drug war will be two years old and its effectiveness is debatable. With the drug pushers seemingly unstoppable in their quest for money and power at the expense of Filipino lives, families and communities, the president could be seen as being the underdog. But as we have seen time and again, Hollywood loves underdogs.

In the climax of Scarface, Tony Montana makes a last stand in his mansion against a drug lord’s invading army. He grabs a machine gun with a grenade launcher and makes his way to the front door. “Say hello to my little friend,” he growls in his cocaine-fuelled rage before wiping out a few henchmen. Ultimately though, he is outnumbered and outgunned and dies in a pool of blood, a victim of his own greed. If he’d had a few more friends though, things might have been different. ■