India’s lynching app: who is using WhatsApp as a murder weapon?

Social media disseminates ‘fake news’, stoking ethnic and religious hatred for an ill-informed public

When the mobile telephone revolution swept India – a country where landline phones used to be hard to obtain – there were whoops of joys. Mobile telephony, said the experts, would transform India.

And it has indeed. At present there are 730 million mobile phone users in India. Of this, at least 340 million have smartphones with internet and video. The growth of mobile phones has outstripped nearly everything else. A 2016 study found that 88 per cent of all of India’s households had mobile phones. In contrast, about 60 per cent of all households have access to basic sanitation. (The government’s figure – much disputed – is slightly higher at 65 per cent.) And only around 64 per cent of all households own a TV set.

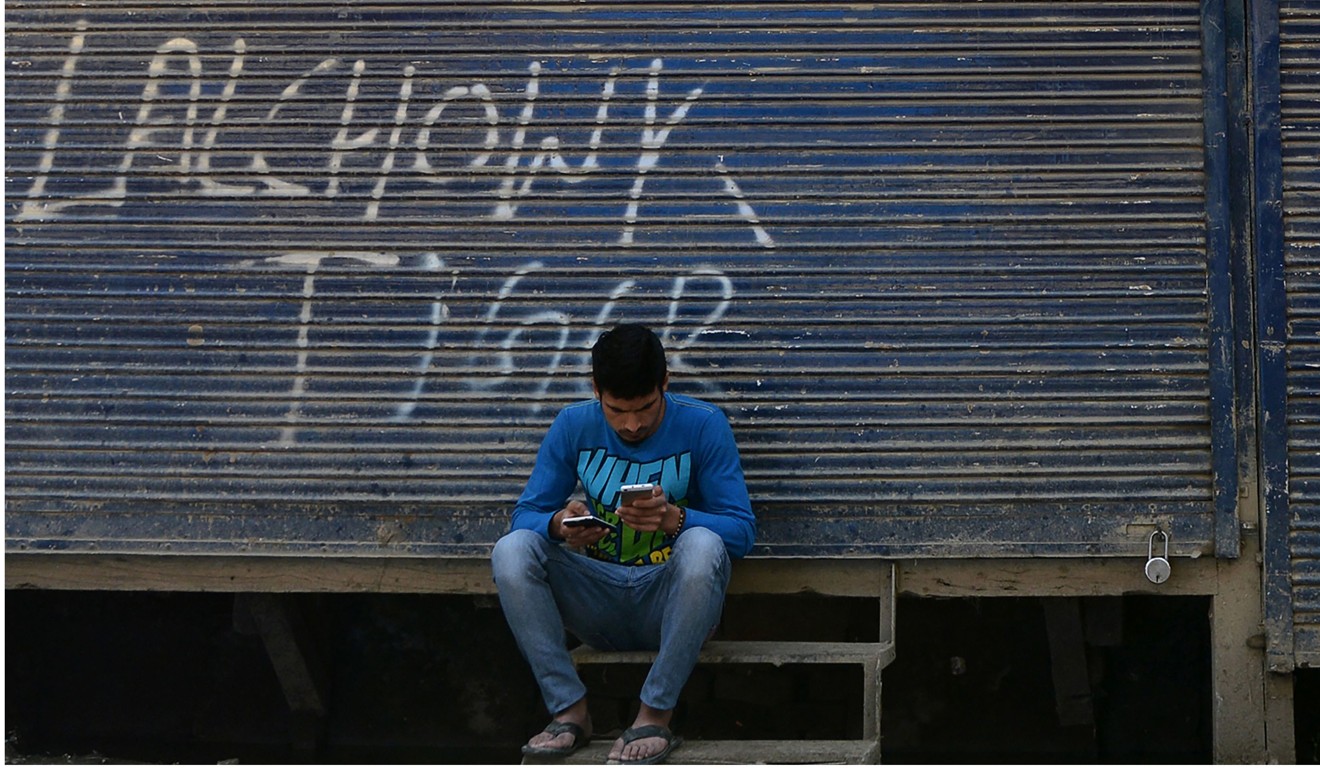

The smartphone revolution has changed the way Indians receive information. In 2014, the election campaign of Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party focussed on social media with dramatic success. And now, WhatsApp is a primary source of information for millions of Indians – with worrying consequences.

The most dangerous of these consequences has been the rise in the lynching of innocent people because of fake news and rumours disseminated on WhatsApp. On July 6, the Indian army had to be called in to disperse a large mob that was trying to lynch three men in Mahur in India’s eastern state of Assam. Police had to rescue three others from a nearby village. The lynch mobs were incensed by false news carried on WhatsApp about childlifters.

In June, two men were beaten to death in another Assam town after similar rumours spread on social media.

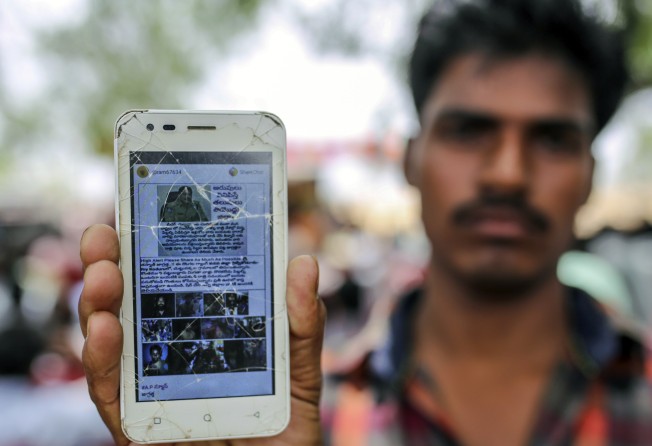

Over the past two months, at least 20 people have been lynched following false stories posted on WhatsApp about supposed kidnappers. More than simple rumours, these fake stories are often well-crafted and designed to look like genuine news.

A week ago, five men were beaten to death in the western state of Maharashtra after a video about the slaughter of children to harvest their organs was circulated on WhatsApp. The video used pictures from a nerve-gas attack in Syria and claimed that these were local children who had been kidnapped and killed.

While Indians are used to rumours, the WhatsApp stories are particularly potent because they reach people who have come to regard their smartphone as their primary source of information, rather than newspapers or TV news. As far as they are concerned, if a video is forwarded to them on WhatsApp, it must be true.

According to DataSpend, a public interest journalism website, 33 people have been killed in 69 mob attacks so far this year. Before that, only one such attack was reported, in 2012.

The Indian Express newspaper, which has been investigating the app-fuelled lynchings, has found that the false stories all follow a pattern. They are set in areas where no previous case of child lifting has been suspected and the victims are usually strangers passing through the area.

The police are usually outnumbered or ineffectual in responding to the rage these fake news messages fuel. When victims seek refuge in police camps, the camps themselves are stormed. And on one occasion, the mob dragged victims out of a police jeep.

If the anger is sudden and spontaneous, the fake stories are not. Clearly, people with money and skills take part in creating the fake videos. In many cases, the footage used is sourced from all over the world. It is edited, manipulated and then spliced together to suggest that it is of recent local origin.

So far, at least, the authorities say they don’t know who is making these false reports or what their motives are, though the catalysts are not hard to decipher.

The celebrated Urdu editor, Shahid Siddiqui, says that part of the agenda is to turn Hindus against Muslims. “They use fake or distorted footage from elsewhere to suggest that Muslims are murderers or rapists of Hindu women and then forward them through social media. These videos reach villagers and poor people with no access to any other information and they start believing that Muslims are monsters.”

After the lynchings in Maharashtra, the state government contacted WhatsApp, and its operators said they were horrified. The police say they are powerless because once a WhatsApp message has been forwarded several times, it is virtually impossible to trace it back to the original sender. WhatsApp responded by suggesting that it will design tools to distinguish forwards from simple replies.

Some experts have suggested that all social media accounts should be linked to Aadhar, India’s Unique Identification System, so that the police can track down each person who posts fake news. But since foreign servers are frequently used by those who use WhatsApp to spread lies, such a move might have a limited impact.

Meanwhile, aware of the power of social media, India’s political parties are stepping up their WhatsApp budgets in the run-up to next year’s general election. They recognise that the service offers the best way to reach less sophisticated voters, and that includes those unable to tell the difference between news and fake news, between truth and lies.

And there is now a little less rejoicing about the smartphone boom, since its dangers and consequences have sometimes been written in blood.