China has a big fat problem with US-style ‘body positivity’

What’s the healthiest approach: making people feel comfortable about their obesity … or fat-shaming our way to more healthy lifestyles?

Love on a Diet was a 2001 Hong Kong romantic comedy starring Andy Lau and Sammi Cheng in fat-suits. Lau’s character helps Cheng’s character lose weight so she can win back her handsome Japanese boyfriend; Lau himself then slims down and the two find love together. There was no suggestion that fat people should be loved for who they are rather than their physical appearance, or that body-shaming men should be shown the error of their ways. The moral of the story was if fat people slim down, they can find love and happiness.

This is still the norm in China: overweight women who want to get married need to slim down or risk staying single. The alternative for overweight heterosexual women is to hope they will meet one of the men in China who do not care about size – which is a problem, since there are probably only about a dozen such men in the whole nation, and they’re married.

This contrasts with the current Western penchant for “body positivity”, a strong cultural current in Britain and the United States that suggests not only is it wrong to bring attention to a person’s weight, it is also wrong to suggest an overweight person should lose weight. Dove, the soap brand, led the charge a decade ago with a series of advertisements featuring beautiful, cheery overweight women in their underwear. To liberal-minded people, body positivity is good, while its opposite, fat-shaming, needs to be rooted out and destroyed.

An extreme example of the latter occurred in February 2018: Sofie Hagen, a Danish comedian, responded with an expletive-laden diatribe to a Cancer Research advertisement that warned obesity was the number one cause of cancer. The concept of “body positivity” as interpreted by Hagen meant that you cannot suggest fatness has any negative attribute – even if you are trying to save lives.

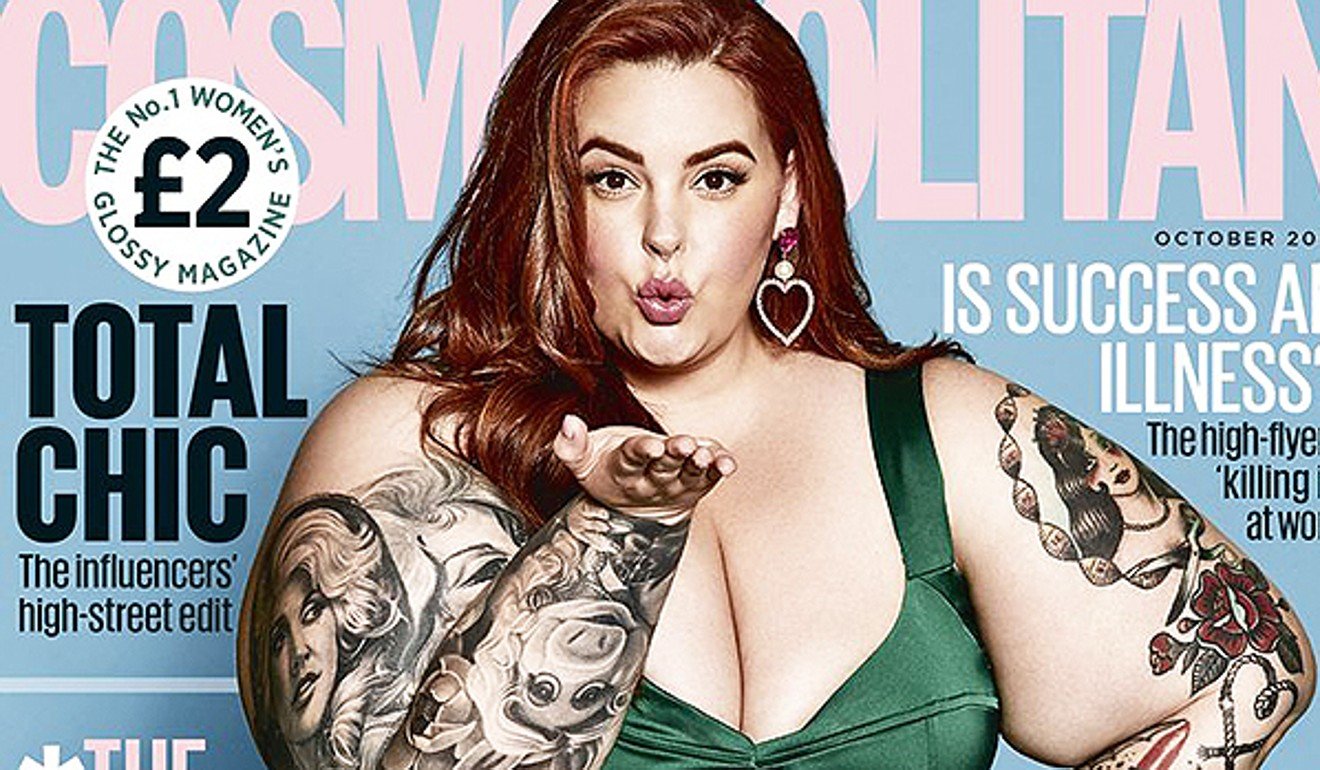

More recently, Cosmopolitan magazine chose a beautiful but obese model as the cover girl for its October edition. In the West, fatness has become a moral issue: the Cosmo cover provoked debate that centred on whether the magazine was inadvertently promoting physical ill-health by normalising obesity, or promoting mental health by giving overweight women confidence.

In the same month, China’s Sina.com published a photo story called “She decided to diet after being rejected for being too fat. Now it’s the boys who are chasing her”.

In this story, there was no moral judgment at all, but there was plenty of physical judgment: she was too fat, so, not surprisingly, the boy she fancied turned her down. She slimmed down, and now look at her. The boy changed his mind, but: too late! If you didn’t like me when I was unattractive then you don’t deserve me now I’m pretty. The article concludes with “Boys, take note. If a plump girl is interested in you, don’t reject her. Help her lose weight, and you’ll have yourself a hot girlfriend.”

How many people in mainland China really think this way? Societal surveys in the country are hard to conduct – not least because of legal restrictions on them, but we do have an excellent study of Singaporean women by Weiting Jiang, Janice Tan and Daniel B. Fassnacht of the Australian National University.

They surveyed anti-fat bias and its effect on behavioural intentions using three types of measures: implicit, explicit, and a revised behavioural intention measure. Participants exhibited strong implicit but no explicit anti-fat bias. The study found that implicit anti-fat bias is present among Asian females and is a valid predictor of weight-related behavioural intentions. However, anti-fat bias is often not expressed explicitly, and the authors believe that the sampled women are influenced by collectivistic beliefs. In other words, Singaporean women dislike fatness, but don’t admit it.

In mainland China, while social surveys are hard to come by, anecdotal evidence is voluminous. The semi-mythical appreciation of fat women epitomised by Tang beauties such as Yang Yuhuan is just that – a myth. Compared with the results of the Singapore survey, it seems that the more down-to-earth Chinese response includes much more explicit dislike of fatness.

The blogger Chara Chan (who was born in Sichuan) describes how China is perhaps more tolerant in some ways than Singapore, Korea or Japan (where women diet with vigour and fury). Chan nevertheless feels Chinese people are explicitly biased against fat people, especially women. She gives great examples which many readers will be familiar with:

1. Being introduced to someone for the first time, who responds to the introducer “she isn’t fat at all” – thus revealing that she had previously been referred to as fat.

2. Being told by shop assistants in clothing stores that there is no point trying on certain items of clothing because “you’re too fat”.

Amazingly, China now has the largest overweight population in the world – 10.8 per cent of men and 14.9 per cent of women in a nation of 1.4 billion people – forcing the traditionally gluttonous US to second place. For children and young adults, the numbers are worse: the World Food Programme suggests that 23 per cent of boys and 14 per cent of girls under 20 are overweight or obese.

Despite this, rates of obesity for the Chinese population as a whole are still far below American or British norms. Two thirds of Britons are overweight or obese. Tellingly, a study published last year in Psychological Science, the journal of the Association for Psychological Science, found Asian Americans who are overweight are viewed as more “American” than those who are not. So if you’re Asian in America, you can munch your way to cultural acceptance. And in China, self-identification as “fat” has changed in a generation. In the 1990s it would not be unusual to hear a woman with a BMI of 24 claiming to be fat, whereas this absurdity is less likely now there are so many fatter people around.

Chinese men suffer comparatively few of the societal problems associated with weight. While they are just as likely to suffer health problems, their job and marriage prospects and their mental health do not seem to suffer, suggesting that women’s struggles with weight are heavily influenced by societal norms.

This brings us back to the questions raised by that Cosmopolitan cover. Is it better for society to take the Western approach, and attempt to change people’s perceptions? Should we try harder to ensure that everyone is comfortable with their weight – even when they are obese? Or should we take a more Chinese approach, and focus instead on reducing the likelihood that they become fat in the first place? The former approach would no doubt comfort fat people, but since it would erode the social stigma attached to obesity it would also presumably increase the obesity rate. The latter approach, however, might well reduce obesity-related health problems in the population, but would probably increase the mental anguish suffered by fat people.

What do we do? In the West, for every Adele there are two Taylor Swifts. In China, for every Han Hong (who isn’t even that fat) there are 99 GEMs – whose very name stands for Get Everybody Moving. When will China have a fat movie star or pop star who isn’t just there for comedic value? My guess is never. The rest of the world will eradicate fatness before Chinese people come round to body positivity. ■